plein-air, photography

#

plein-air

#

landscape

#

photography

#

realism

Dimensions: height 5 cm, width 5 cm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

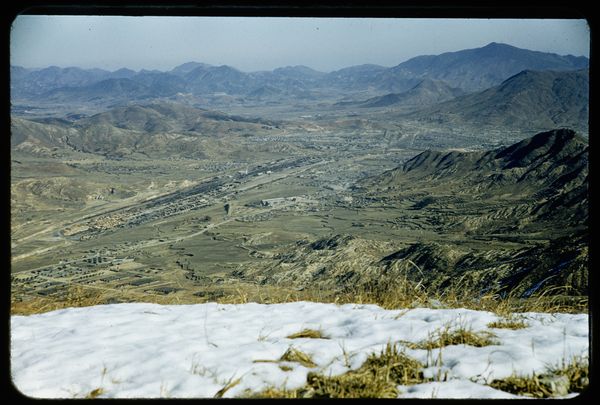

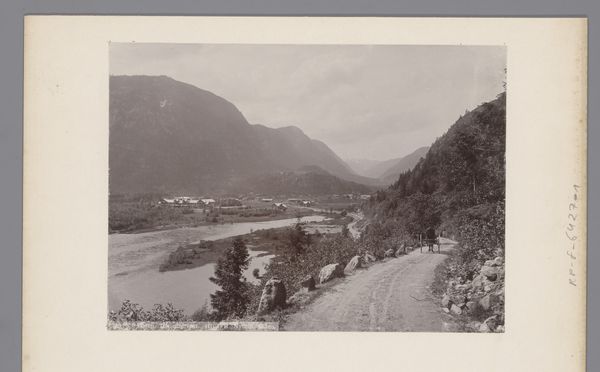

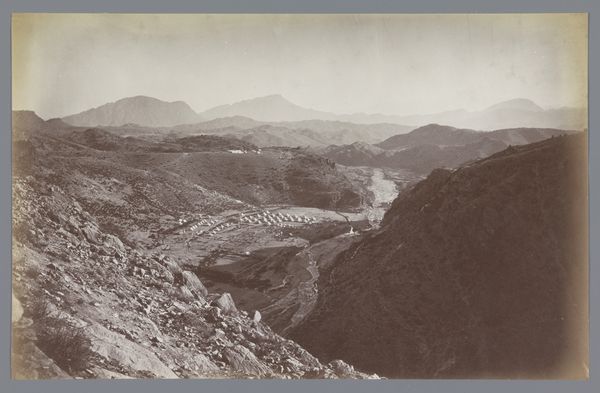

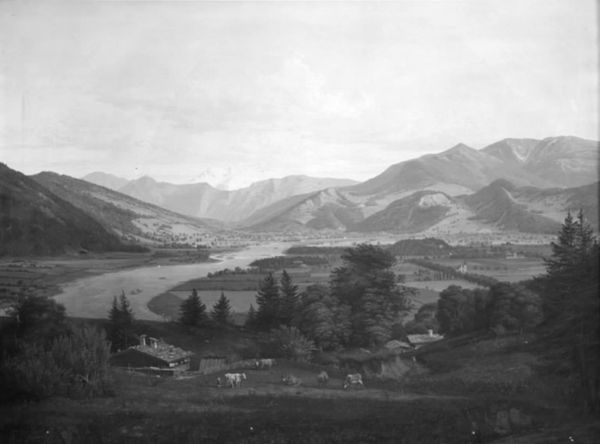

Curator: Here we have David Ketel’s “Legerkamp bij Busan,” or “Army Camp near Busan,” created in 1952. This plein-air photograph presents a broad, elevated vista. Editor: It’s initially quite serene, almost idyllic. The hazy mountains fading into the background give it a classical landscape feeling, and then you notice the organized, geometric harshness of the encampment itself. Curator: The composition leads the eye deliberately. The foreground is dominated by these almost painterly rocks. From there, our gaze travels into the valley and towards the network of shapes suggesting settlement and order amidst the nature. The horizon is atmospheric, recessive, in the way we often observe in landscape painting of that time. Editor: What strikes me is the implicit tension. This image was made during the Korean War. The vista, normally an opportunity for sublime appreciation of the landscape, is here framed by the military's presence. This juxtaposition feels charged—as if it is observing how even pastoral spaces were conscripted into geopolitical conflicts. Curator: Exactly! One can certainly analyze Ketel's framing. The framing foreground allows for an aesthetic assessment of light and shade—which he accomplishes beautifully. Editor: Yet one also cannot ignore the broader implications of war—displacement, colonial legacies, even the violence enacted upon the very landscape to accommodate this "camp." A tension exists, visually, and historically. Curator: I understand your argument, but isn't it the masterful contrast between order and wilderness that allows us a window into Ketel’s process? A study in shapes that become narrative because of that intentional imbalance? Editor: And isn’t it in understanding the complex conditions under which this photo was created that we start to understand why we find the visual construction so unsettling? I suppose both lenses are vital. Curator: Indeed. We see formal choices as narrative, informed, as ever, by an intersectional context. Editor: Ultimately, Ketel leaves us considering what it means to build a space of conflict within a landscape, and to view that tension with something resembling artistic appreciation.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.