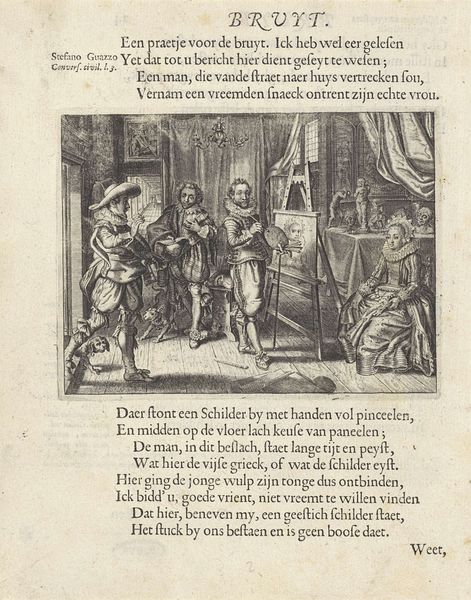

engraving

#

portrait

#

dutch-golden-age

#

figuration

#

genre-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 66 mm, width 78 mm

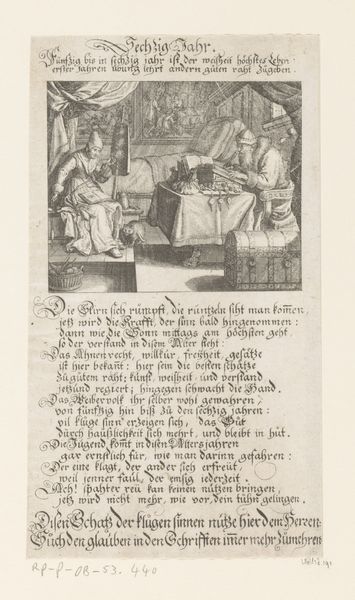

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

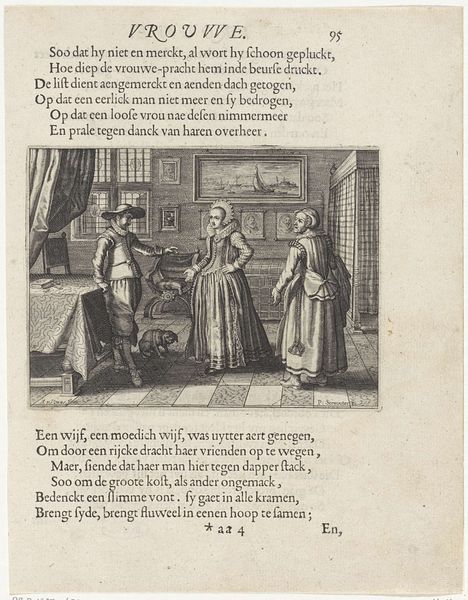

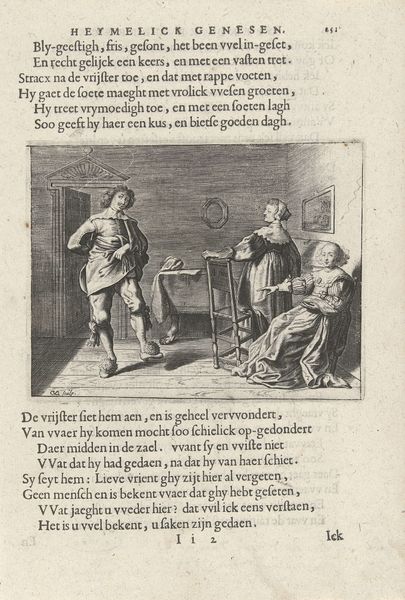

Curator: This engraving by Crispijn van de Queborn, from 1643, depicts Hipparchia and Krates, now held in the Rijksmuseum. The entire piece strikes me with its simplicity and lack of ostentation, despite clearly representing an upper-class interior. Editor: It feels somewhat claustrophobic. The horizontal lines of the paneling and the figures being crammed in...there's something stiff about its spatial arrangement, almost purposefully anti-perspectival. What catches your attention most formally? Curator: I am drawn to the contrasting textures Queborn manages to evoke. Notice the precise lines used to define the volumes of the clothing. Hipparchia’s dress has a beautiful cascading rhythm of light and shadow as her robes fall into swaths on the floor, and that bundled cloth near Krates--it has an astonishing softness despite being rendered entirely in hard lines. How is this accomplished with simple tools? Editor: And it’s these "simple tools" that interest me! Engraving is additive; a whole process. To achieve softness the artist needed skilled engravers who had acquired experience to properly incise metal in tiny movements—the tools themselves tell of knowledge exchange throughout generations in workshop settings. The contrast you note could indicate varying degrees of specialisation across collaborators in Queborn’s studio. The engraving becomes a record of embodied skills within the system of print production. Curator: Perhaps, but consider the intellectual concept! The positioning of the text gives an explanation of the picture—in this scene, Hipparchia is turning away from a more traditionally luxurious life—symbolized by the renounced objects around her, rejecting the social expectations of the time. The visual and literary aspects of the engraving work hand-in-hand to communicate complex philosophical notions about autonomy. Editor: I'm drawn to those cast-off trappings, the robes in particular. Their rumpled state reminds us that materials hold stories of prior use—labor, wear and tear—a stark contrast to how value is usually conveyed through clothing depicted in this period’s more idealized portraits, which so carefully masked such lived-in quality. It’s the unglamorous aspect, the discarded fabric, that pulls you into another social orbit that valued different objects, and therefore, labor. Curator: I find myself moved by the quiet strength suggested by the image combined with the poem—her devotion is clear, even understated, emphasizing an emotional depth. Editor: I agree; examining the material transformation illustrated in the scene provides another means for entering these early social tensions, too, prompting us to examine not just ideas, but lives materially impacted in subtle ways by radical life decisions like this one.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.