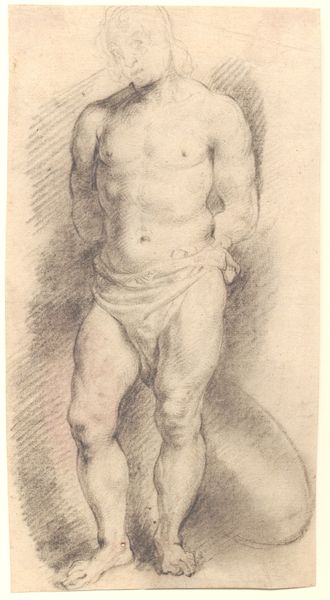

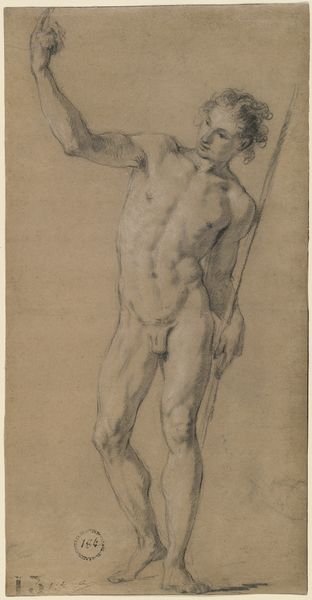

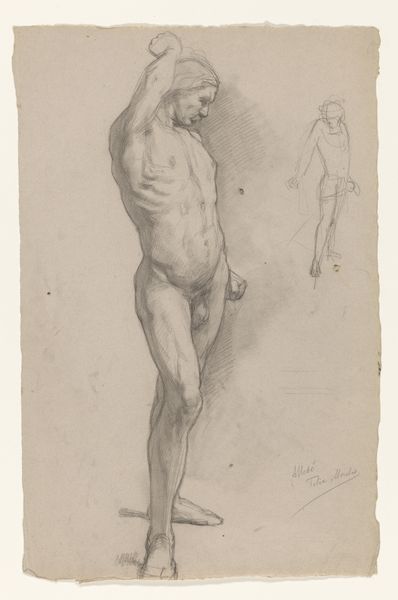

Study of a Standing Male Nude: Saint Sebastian c. mid 17th century

0:00

0:00

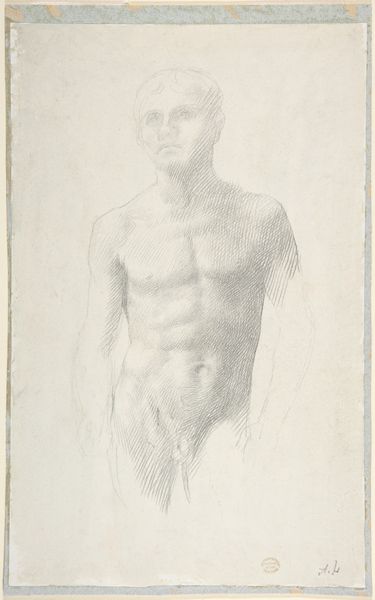

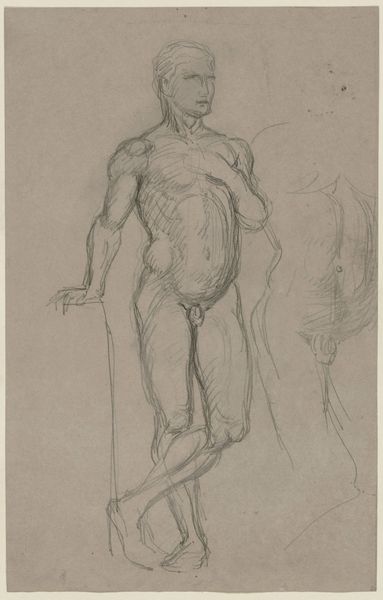

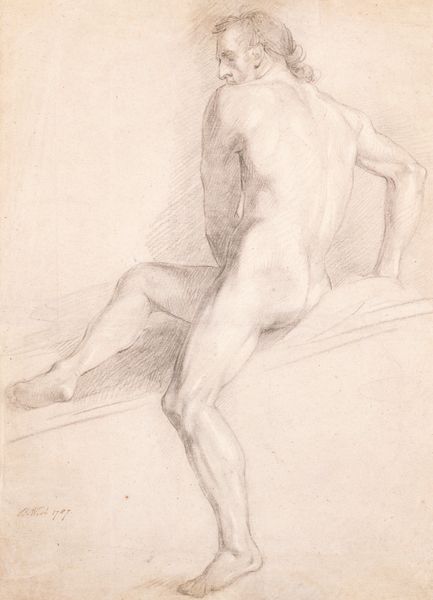

drawing, pencil, charcoal

#

portrait

#

pencil drawn

#

drawing

#

baroque

#

charcoal drawing

#

figuration

#

pencil drawing

#

pencil

#

charcoal

#

italian-renaissance

#

nude

Dimensions: sheet: 41.8 × 24.2 cm (16 7/16 × 9 1/2 in.)

Copyright: National Gallery of Art: CC0 1.0

Curator: Just look at this. "Study of a Standing Male Nude: Saint Sebastian," likely from the mid-17th century by Jacopo Confortini. It’s a pencil and charcoal drawing, a preparatory sketch perhaps, but so full of life. Editor: There's an inherent vulnerability in a nude figure, and this piece captures that, but there’s also defiance. The subject's stance seems almost casual, though his arms are bound. I find the contrasting tones quite compelling; it is baroque. Curator: It’s a tension Confortini so masterfully balances, isn't it? Sebastian, the martyr, often depicted riddled with arrows, becomes an emblem of resilience. Yet here, he's a man stripped bare, figuratively and literally. I’d also call it portraiture. Editor: Indeed. Considering this work in its historical context, we see the evolving relationship between the Church, the state, and representations of the body. Saint Sebastian’s image becomes a battleground for cultural values and ideals of masculinity. Is this Sebastian anticipating the arrows to pierce his body, or reflecting after survival? Curator: Good question. Perhaps both? The ambiguity heightens the emotional resonance, doesn't it? I’m also drawn to the artistic process visible here—the layering of pencil and charcoal. You see the artist searching for the form, almost like an act of discovery. A bit rough, maybe? Editor: The artist seems unafraid to reveal his process. It democratizes art, or at least the idea of it, which otherwise seems so codified and austere when viewed, centuries removed, in this quiet hall. I find it very direct, if not intimate. Curator: Exactly. He's rendered beautifully yet brutally. A god made mortal or vice-versa. To me, there is also a homoerotic subtext; how does that connect with martyrdom? It is the nature of pain versus a path to salvation through suffering, which gives it profound meaning. Editor: And by unveiling the power structures and the politics of pain represented in art, we can begin to better understand not only the art of the past but also our present condition, particularly how museums like this one curate an interpretation of those pasts. Curator: It makes one pause, contemplate, even reconsider the weight of cultural baggage we bring to art and museums and what their lasting impression is on our subconscious selves. A fine feat for one simple drawing. Editor: I’m struck how a single artwork can act as a nexus for history, art, belief, doubt, power, fragility and offer a compelling lens for analyzing ourselves as active observers.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.