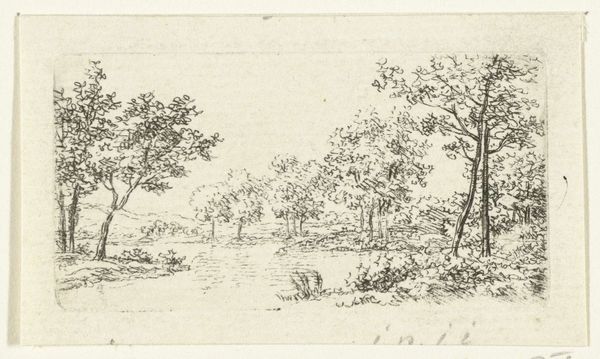

print, etching

# print

#

etching

#

landscape

#

geometric

#

romanticism

#

line

Dimensions: height 82 mm, width 101 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Looking at this etching from 1827, entitled "Rivierlandschap," by Reinierus Albertus Ludovicus baron van Isendoorn à Blois, I immediately feel a sense of calm, a gentle invitation into a world viewed through a specific, artistic lens. The use of line to define form is striking. Editor: Yes, it is a rather quiet landscape, isn’t it? I see the idealized romantic vision of nature—nature here acts as a refuge away from societal pressures. But is it truly ‘calm’, or perhaps ‘complacent’ in its idyllic framing, detached from the socio-political turmoil brewing in the Netherlands at this time? Curator: Well, the artist was, in fact, a baron, so his lived experience was likely one of privilege. The composition is consciously framing nature in a controlled manner, so I wonder, what did landscape mean to the elite during this period? Was it pure escape or perhaps also a declaration of ownership, control? The placement of the distant geometric structures reflected on the river – how did this aesthetic fit within broader societal ideas? Editor: Exactly. And while the print medium makes this image accessible in some ways, to whom was it *really* accessible? Land ownership at this point was, for the vast majority, exclusionary. So that calm you mention—who *could* actually experience it? For much of the rural populace, it was more of a back-breaking reality than a moment of serene contemplation. Is that small estate house nestled along the shore indicative of peace, prosperity and privilege? The cultural connotations and elitist associations surrounding images are impossible to ignore. Curator: That tension is indeed ever-present in landscape art of this period. The lines, rendered via the etching, are delicate. Look at the subtle gradations of light as they play across the water, or the intricacy in the foliage. It creates a depth that really draws you in—a kind of controlled invitation. There is an illusion to its constructed paradise—but also, it acknowledges human interaction with nature. There is order amidst the wildness. Editor: I suppose appreciating the beauty of this Rivierlandschap while interrogating its socio-political implications can indeed co-exist. We might find this composition, with the darker forms on the sides framing a central, lighter opening, is referencing Claudian landscapes – a way of legitimizing through association. Curator: Perhaps appreciating, or simply encountering, art requires accepting a dual existence: appreciating its beauty and artistic merit while confronting any underlying sociopolitical assumptions that existed in the past and may still resonate today. Editor: Indeed. It seems a key part of interpreting artworks of the past involves this delicate balancing act: aesthetic enjoyment is not diminished by historical awareness.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.