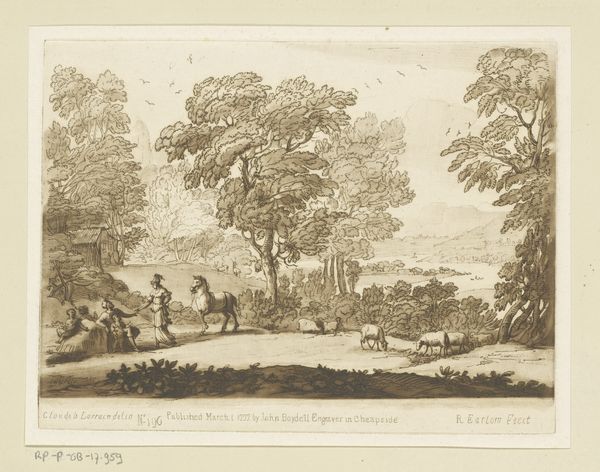

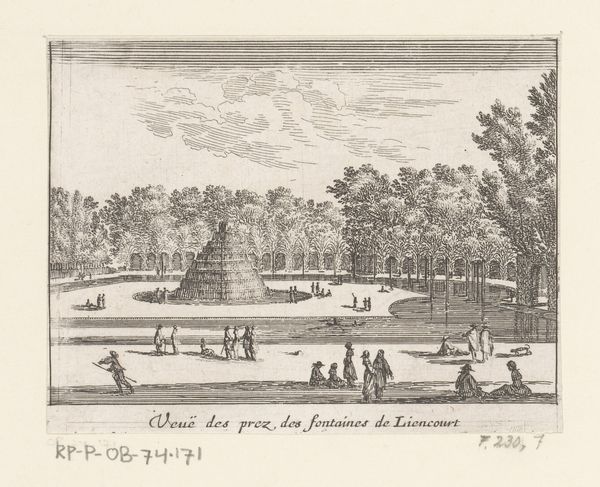

print, etching

#

dutch-golden-age

# print

#

pen sketch

#

etching

#

landscape

#

etching

#

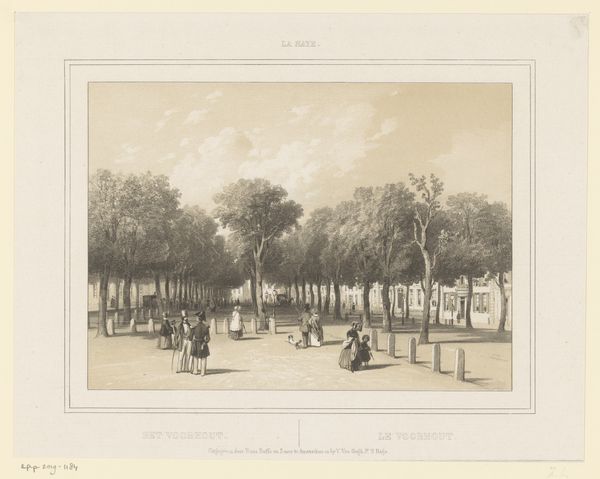

romanticism

#

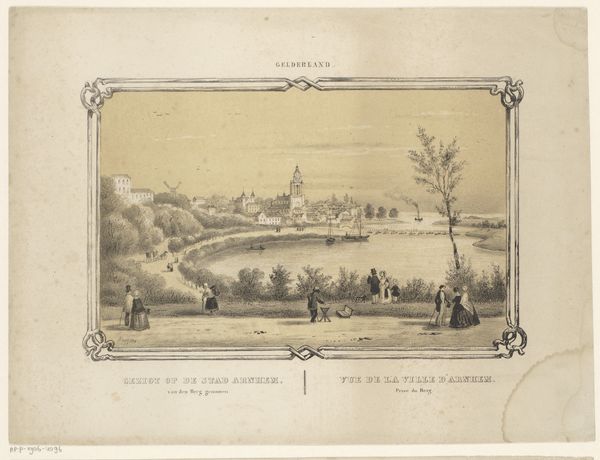

cityscape

#

genre-painting

Dimensions: height 220 mm, width 305 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

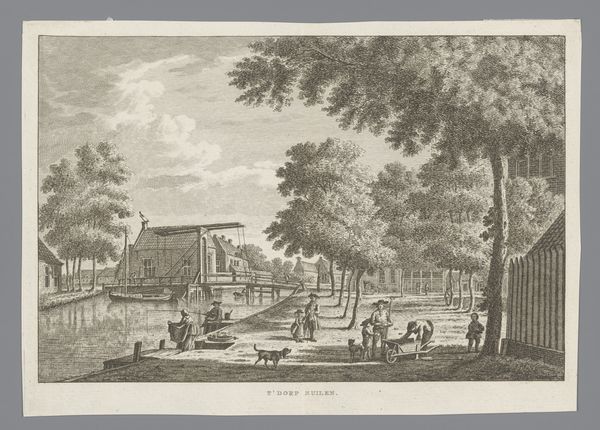

Curator: Hendrik Wilhelmus Last's "View of the Nieuwe Plantage in Rotterdam," dating back to 1850, gives us a glimpse into a vibrant Dutch cityscape. It's a print, skillfully rendered through etching. What's your initial take? Editor: It strikes me as incredibly picturesque, almost like a stage set. The soft, muted tones lend a sense of tranquility, but I also notice a distinct social stratification on display. Curator: Absolutely. Landscape, and particularly cityscapes in Dutch art, are filled with symbolism. Think about how the composition directs our eye: the orderly park and promenading figures juxtaposed against signs of industry in the distance. It highlights a society navigating modernization. Notice, too, the ornamental border which seems like a picture frame, yet with overflowing, natural images and city symbols at the top that include an almost imperial crest of Rotterdam, framing and authenticating this vista. Editor: Yes, the figures really animate the scene. We see everything from bourgeois families to a lone laborer with a scythe. How does the "Nieuwe Plantage" function here, not just as a real location, but as a representational space for diverse social groups? Curator: Consider the idealized romanticism of the era. While the scene appears harmonious, one could argue that it sanitizes the complexities and inequalities inherent in 19th-century Rotterdam. The city is growing and booming, but class and labor structures remain stark. This location is not merely "New Plantation," as named in Dutch. It's also suggestive of classist implications within Dutch colonialist enterprises elsewhere at this time. Editor: That’s a critical point. These seemingly benign scenes often subtly reflect the power dynamics of their time. By aestheticizing everyday life, are they normalizing potentially exploitative labor practices and burgeoning disparities in wealth and land use? The image offers a vision of a “romantic” Rotterdam but does not offer the entire view, so to speak. Curator: Precisely. What appears celebratory may in fact reflect deeper systemic issues that continue even into our own time. I’d say that it presents itself as both descriptive and aspirational, a common dynamic within Romantic-era imagery that, from the perspective of semiotics, seems both clear and coded, but not without ambiguity. Editor: That prompts an interesting way of reading visual history—seeing an image as both a product and producer of cultural narratives, where “history” offers much more than one view. I see so much room to unpack within this seemingly idyllic scene. Curator: Indeed. It’s a perfect example of how artworks can function as windows into the past, sparking complex dialogue even centuries later.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.