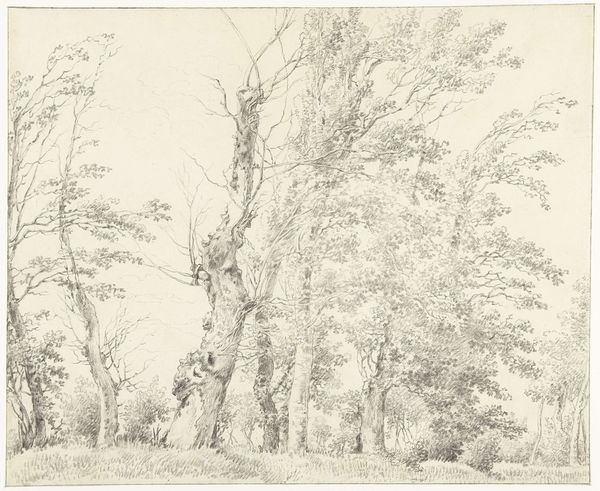

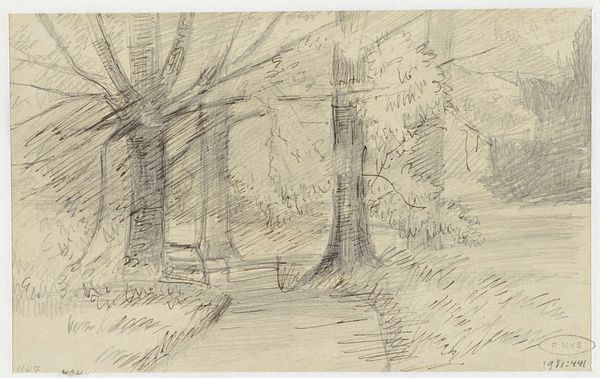

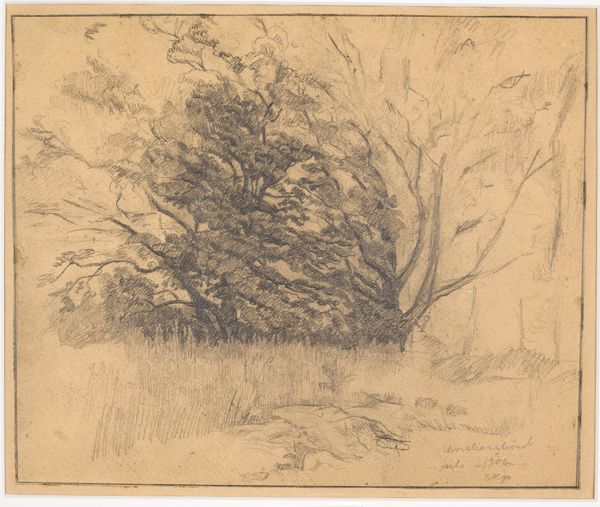

Dimensions: height 260 mm, width 404 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

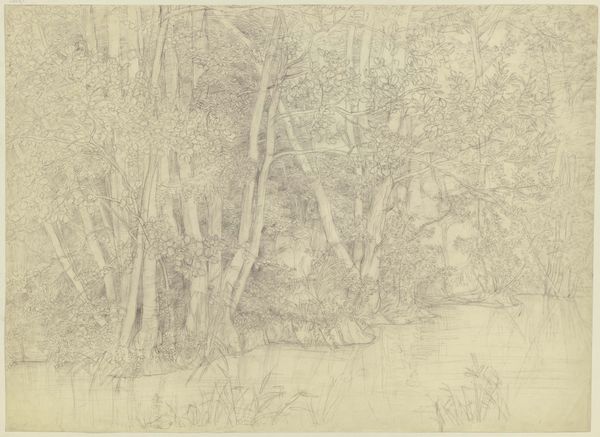

Curator: Here we have Eugène Delacroix's "Gezicht in een bos," possibly from 1858, residing here at the Rijksmuseum. It’s rendered in pencil. Editor: Immediately, the intricacy of the pencil work grabs me. There's a dense layering that suggests not just a visual representation but also a sensory experience of being enveloped by the woods. The varying pressures used give an almost tactile dimension to the leaves and trunks. Curator: Absolutely. Delacroix, steeped in Romanticism, often explored themes of nature as a powerful, sublime force. It reflects back to broader dialogues happening during his lifetime as Europe shifted with both the aftershock of revolution and rapid industrial advancement. Where did the wilderness fit, both politically and emotionally? Editor: And look at how he employs the pencil to mimic the density of the forest. Pencil, as a material, is humble. Accessible. Here, it’s a democratic choice almost, yet used to represent a complex and imposing ecosystem. Think of the labor, too. This level of detail implies a dedication of time, a focused practice almost meditative in quality. Curator: Considering Romanticism, there's often this notion of the individual's experience within that vast landscape. Is there an interrogation here then? A sort of subtle critique embedded in this representation? If the means is indeed accessible, what statement, if any, does that accessibility create? Editor: It's the sheer number of pencil strokes used. A huge commitment when there was such poverty still around the consumption of materials in such large quantities speaks to not only Delacroix's affluence and comfortability but also his awareness that there can be time for things beyond work, class, and daily drudgery. He would likely have to work and sharpen dozens of pencils over what might seem quite basic to people like you or me, highlighting the difference in resources needed for his output in terms of drawing as work versus his position and wealth. Curator: That focus on the physical effort underscores an awareness, possibly even unease, about class divides. Even through his artistic gaze, the forest may become this stage upon which socioeconomic disparities are tacitly acknowledged. It's a very astute reading, reminding us art never exists in a vacuum. Editor: So, while initially drawn to its intricate details and my assumption of luxury or indulgence from what initially may seem like overdrawing something "simple," examining his practice more deeply reveals this tension of resources. It urges us to always question our first material response to such pieces, right? Curator: Precisely. Hopefully that interplay provides an even deeper appreciation for the art historical complexities as much as the historical socio-political factors in pieces like this, where our subjective perceptions engage within those larger, more crucial contexts.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.