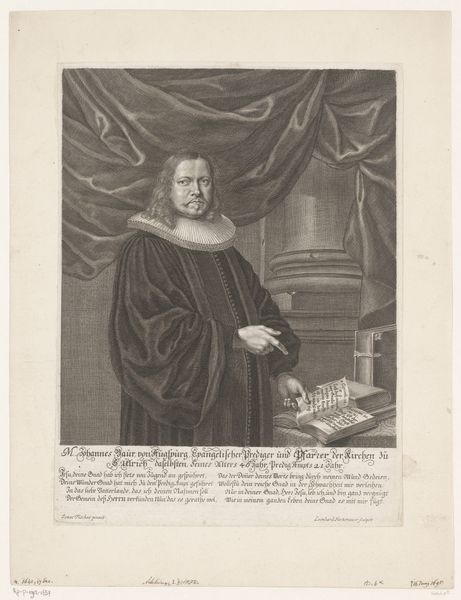

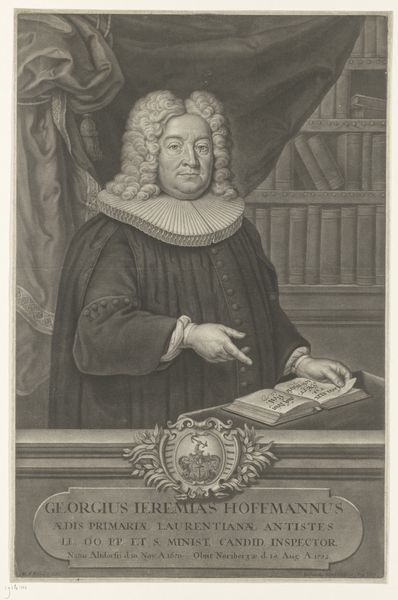

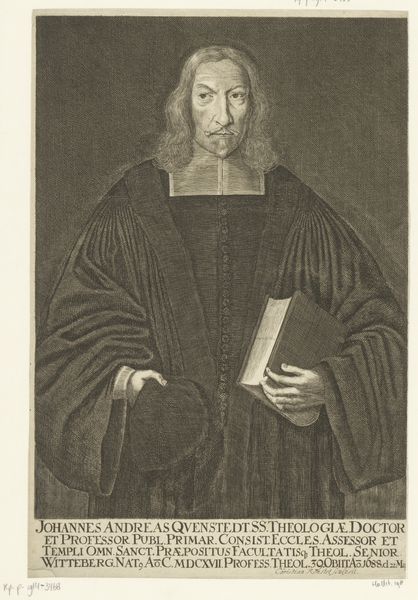

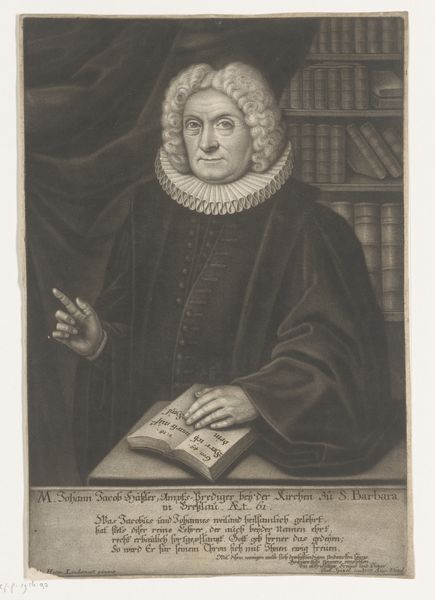

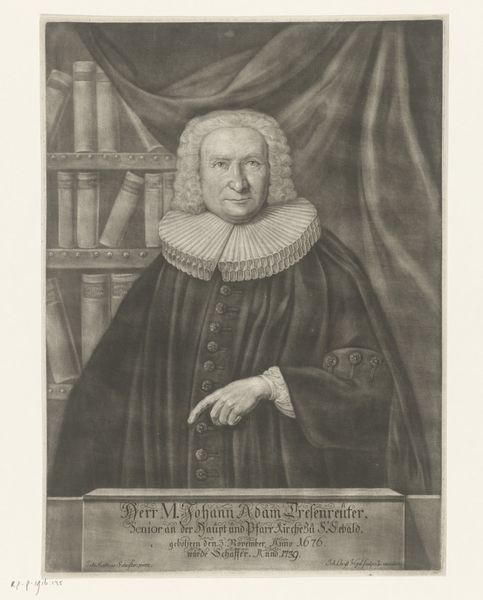

paper, engraving

#

portrait

#

baroque

#

old engraving style

#

paper

#

history-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 351 mm, width 228 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Let’s discuss this impressive engraving now on display here at the Rijksmuseum, a portrait of Johannes Dornfeld, made on paper sometime between 1710 and 1733 by Martin Bernigeroth. What's your immediate impression? Editor: My first impression is about the sheer skill and labor involved. Look at the incredibly fine lines that make up the tones and textures. It's all hatching and cross-hatching. The material reality of creating this must have demanded an extraordinary level of focus and training. Curator: Absolutely. The level of detail, achieved solely through engraving, is remarkable, particularly in rendering the elaborate fabric of Dornfeld's robes. Portraits like this, made by engravers like Bernigeroth, played a crucial role in disseminating images and solidifying the status of figures like Dornfeld within a wider public sphere. Editor: And who was Johannes Dornfeld? His garments clearly convey significance. Curator: Indeed. Dornfeld was a prominent theologian and pastor in Leipzig. The text beneath his image, translated from Latin, spells out his high positions as pastor and superintendent of the Diocese. Notice the open book, too. Editor: Which he presents openly. Look at the crucifix on the lectern near his hand – he wants us to note his association with sacred learning. It is a well-staged depiction of erudition, yet this symbolic staging involved intense physical effort to produce! I wonder who funded or commissioned this print. Was it a public act or a piece of private devotion? Curator: That’s precisely the kind of question a historian asks! Portraits of prominent religious figures often served multiple purposes – celebrating individual achievements, reinforcing social hierarchies, and disseminating religious ideas, so funding may have been communal or granted by individuals who belonged to his inner circle. This portrait certainly captures the gravitas associated with his role. It’s also part of the Baroque style popular then. Editor: Right. From a materialist point of view, each mark contributes to a cumulative image loaded with social weight, made manifest through hours of artisanal craft. Curator: So, ultimately, we see in this portrait a fusion of skill, labor, social significance and faith, forever immortalized in ink and paper. Editor: Yes, a material record of both a man and the network of labor that supports his image, if we understand "image" here also in its socio-political weight, not only an etching on a piece of paper.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.