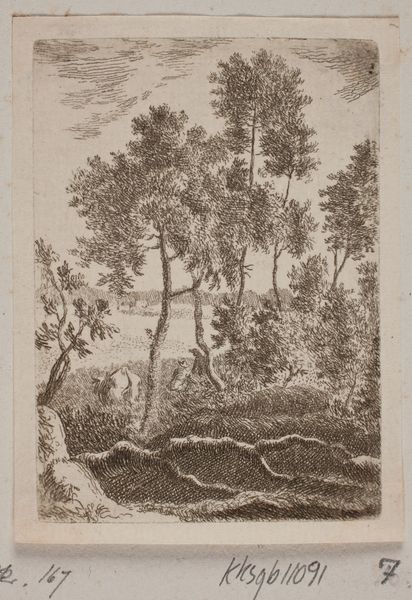

Goldsmith's Bouquet, from Newes Lauberbuechlein 1628 - 1666

0:00

0:00

drawing, print, engraving

#

drawing

#

baroque

# print

#

landscape

#

form

#

line

#

engraving

Dimensions: Sheet: 5 9/16 × 4 5/16 in. (14.2 × 10.9 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: This delicate print, held at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, is titled *Goldsmith's Bouquet, from Newes Lauberbuechlein*. It's an engraving attributed to Peter Aubry II, dating sometime between 1628 and 1666. Editor: My first impression is of something incredibly detailed and slightly overwhelming, like a garden spilling over its boundaries. It's almost Baroque in its density, that swirling mass of leaves. Curator: Absolutely. It’s interesting to note this image originates from a "Newes Lauberbuechlein," or a New Book of Foliage. These books were pattern books, influential visual resources. What sort of visual narratives and meaning might these prints evoke at the time? Editor: Well, these intricate foliage designs weren't just about aesthetics; they directly catered to artisans crafting luxury objects for an elite clientele. This image becomes an instructional object showcasing ideal beauty, implicitly affirming social hierarchies dependent on specialized crafts like goldsmithing. Curator: I find it equally interesting how the print bridges nature and culture. We have, in the lower-left corner of the landscape, rendered so precisely alongside these formalized botanical shapes. Is there any sort of dialogue that may have risen in connection to representations and visualisations of natural forms during this period? Editor: Certainly! Landscapes became markers of national identity and claims to resources. I notice how this detailed design underscores control and the power in defining even the natural world as ornamental. Curator: True. And as for craftsmanship, it speaks volumes about skill and artistry. Think about the physical act of engraving to recreate these fine details on a metal plate; that process itself elevates artistic work as labor, contributing to art's status. Editor: It invites conversations about intersectionality. This piece is deeply implicated within structures of gender, economic, and social power that privileged the patrons commissioning gold work using these templates. The art speaks but the design benefits particular people. Curator: It brings into relief complex societal values attached to objects both functional and symbolic during that era, demonstrating those in power who get to partake in said beauty. Editor: This close inspection forces us to consider broader systems behind not only image production, but also art’s contribution in legitimizing or critiquing prevailing values. Thank you. Curator: Indeed. It shows how what initially looks purely ornamental becomes layered, prompting vital dialogues about artistry and society during the 17th century.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.