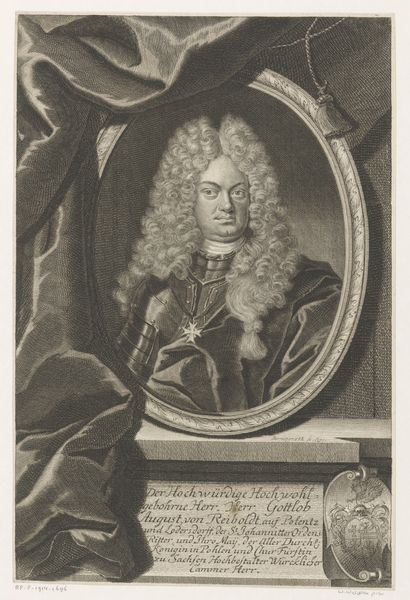

metal, engraving

#

portrait

#

baroque

#

metal

#

history-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 326 mm, width 212 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: This is a piece called "Portret van Karl Wilhelm von Anhalt-Zerbst," dating to sometime between 1680 and 1733. It's currently held at the Rijksmuseum. The artist was Martin Bernigeroth, who worked primarily in engraving. Editor: My initial reaction is one of almost suffocating opulence. The armor, the wig, even the draped fabric in the background—it all speaks of a very specific construction of power. Curator: Engravings like this were often commissioned as prestige items, functioning much like photographs do today but with the added element of skilled artisanal labor. Look closely; you can see the tiny, precise marks of the burin that create the illusion of texture and volume. The social function of the piece becomes very clear through understanding its medium. Editor: Absolutely. Considering the political landscape, how does this type of portrait contribute to shaping perceptions of leadership and legitimacy, especially for someone like Karl Wilhelm von Anhalt-Zerbst? Curator: Von Anhalt-Zerbst clearly understood the power of image. The armour situates him as a leader, not just of people but of military might. I wonder who made that armor, and where the materials came from? Consider the supply chain and specialized labor involved. It mirrors the sophisticated and resource-intensive printing techniques needed for this engraving. Editor: And we should remember that images like this circulated within very particular social strata. Who saw them, and how did their access affect their perception of the aristocracy? It’s important to acknowledge that representations of power are not neutral, particularly along lines of gender and class. Where might ordinary citizens have encountered prints like this one, and to what effect? Curator: I see your point. Mass production also means potential democratization of the image, albeit within very restricted parameters, I grant you. And perhaps it fueled discontent. The original printing process involved meticulous labor, the physical exertion of pushing a burin through a metal plate to create the recessed lines. Every stage speaks to specialized processes, access to materials, distribution networks. These material facts shape our perception. Editor: Right, but considering whose perspectives are privileged, especially in art historical records—I remain deeply skeptical that engravings of nobility can truly function as anything other than propaganda aimed at perpetuating specific social and political systems. Curator: A vital cautionary note, certainly, and grounds for more inquiries into whose voices might be suppressed or lost. Editor: Exactly. By looking at this image with critical awareness of its inherent power dynamics, we gain so much more than simply another historical portrait.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.