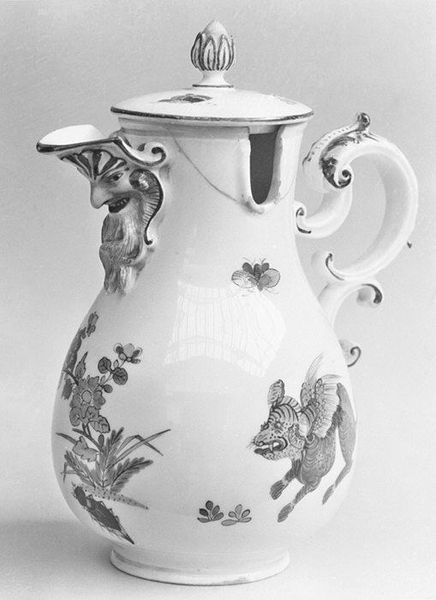

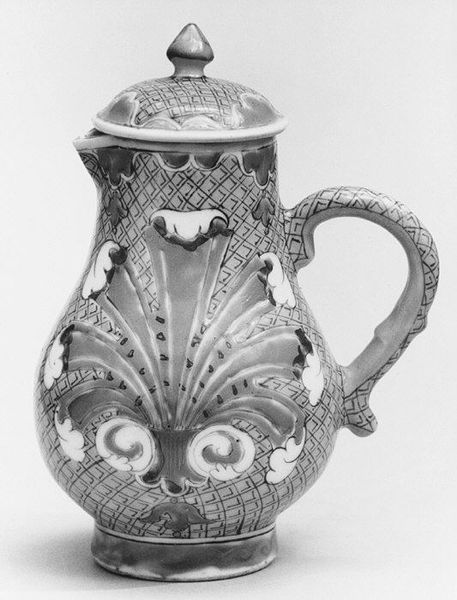

ceramic, porcelain, sculpture

#

ornate

#

decorative element

#

ceramic

#

porcelain

#

sculpture

#

orientalism

#

ceramic

#

decorative-art

#

rococo

Dimensions: Height (with cover): 9 5/8 in. (24.4 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: Good morning! Let's talk about this rather delightful coffeepot from Liverpool, made of porcelain around 1765 to 1775. You'll find it at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. It strikes me as rather playful, doesn't it? Editor: Yes, ornate, absolutely! My initial reaction is whimsy mixed with a definite sense of idealized exoticism. The scenes painted on it feel so stylized; it is a world where even daily rituals have this aura of performance, doesn't it? Curator: Precisely! Notice the Chinoiserie style – those whimsical, slightly inaccurate, and wonderfully imaginative depictions of Chinese life so beloved during the Rococo period. Each figure seems caught in a tiny drama of its own, yet contributes to the pot’s overall narrative. It speaks to 18th-century Europe’s fascination with, and projection onto, the East. Editor: Indeed, it does raise questions about cultural appropriation, or perhaps a lighter "cultural appreciation", but from an imperial gaze, for sure. The imagery seems to borrow vaguely Chinese motifs more for decorative impact rather than authenticity. Look at the "pagoda" next to this figure that looks straight out of a Georgian drawing room! Curator: True, and the floral motifs dancing around the spout and handle further enhance the lightheartedness. One might easily see this piece gracing a grand breakfast table, filled with the rich aroma of freshly brewed coffee. Yet its visual narrative might lead one to consider the origins of that coffee, the voyages that brought it here. Editor: It's a potent reminder of how even everyday objects, like this coffeepot, were, and still are, tangled in global trade and cultural exchange, as well as being icons loaded with implied messages about a long lost era of elegance and good times, maybe gone forever... Curator: Absolutely. Each swirl of its porcelain, each brushstroke tells a silent story about art, trade, aspiration and cultural misunderstanding that we are still unwrapping centuries later. A beautiful object and a silent poem indeed.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.