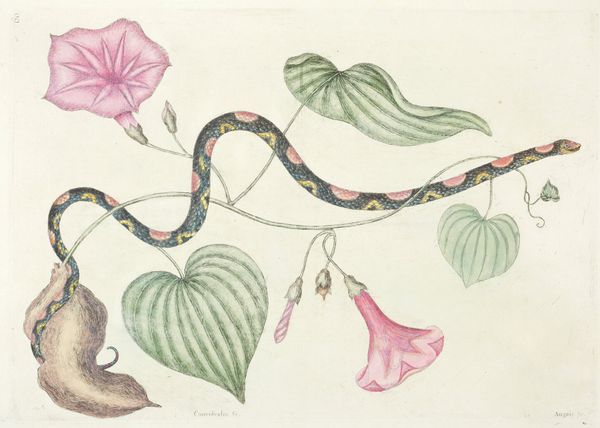

drawing, print, watercolor

#

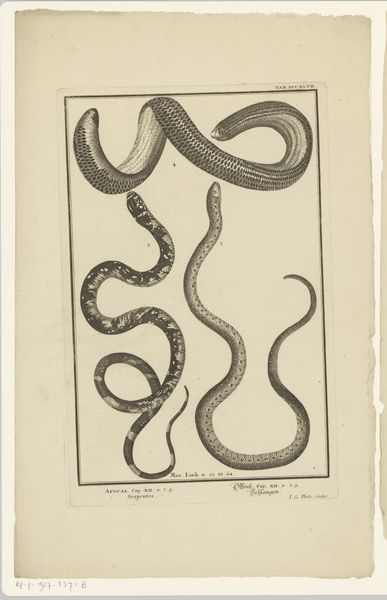

drawing

#

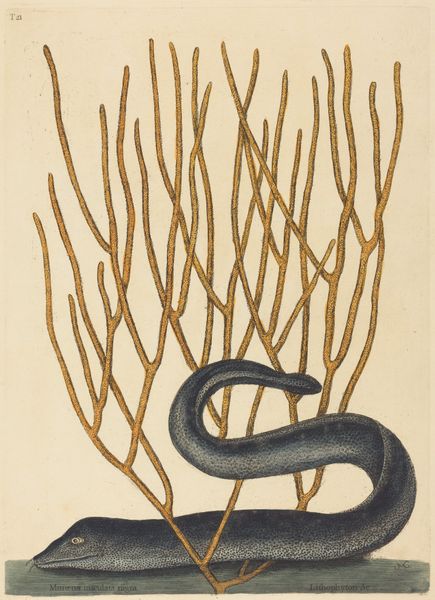

water colours

# print

#

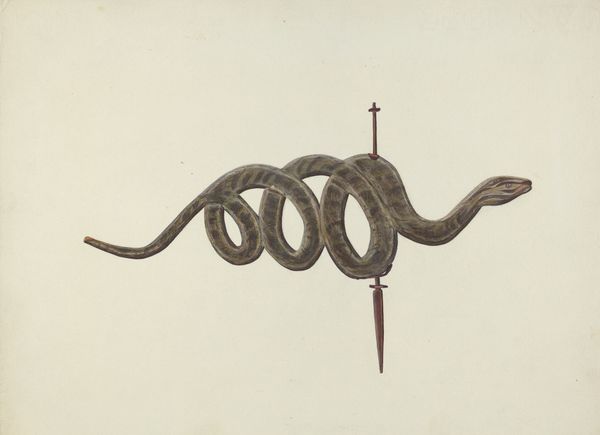

watercolor

#

watercolour illustration

#

genre-painting

#

naturalism

#

watercolor

Copyright: National Gallery of Art: CC0 1.0

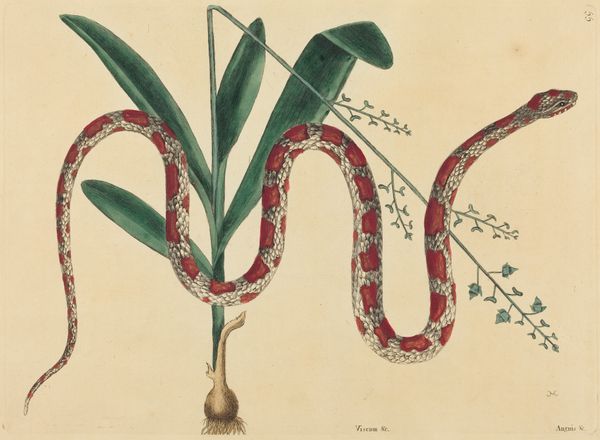

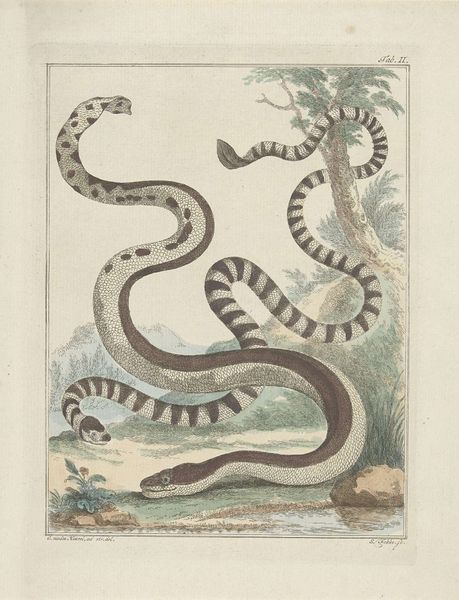

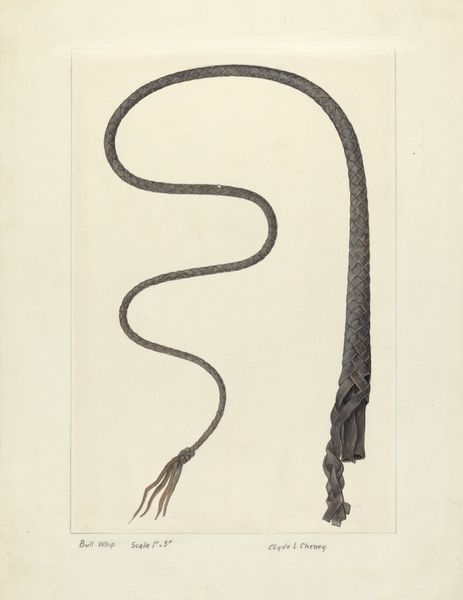

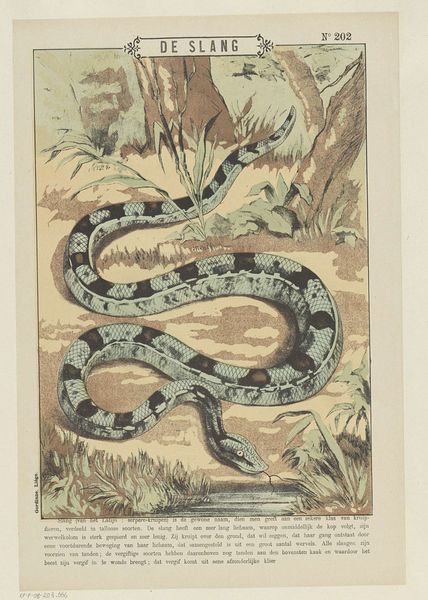

Curator: Mark Catesby’s “The Coach-Whip Snake,” likely made between 1731 and 1743, is quite striking. Editor: My first thought is tension; that serpent is coiled tight, almost defensively. There's something ominous lurking in this seemingly benign natural scene. Curator: The print exemplifies a trend in early natural history illustrations—detailed depictions aimed to document the flora and fauna of the so-called New World. We should really address Catesby's background. His endeavors need interrogating as to his relationship with colonial power and extraction. Editor: Absolutely. And it’s also an example of very specific craft and labor. Consider the printing process involved in reproducing these images and distributing this knowledge, also who was commissioning the works, and for what purposes of use. The texture of the snake, seemingly a watercolour technique, suggests his deep material knowledge. It invites speculation. Curator: He certainly presents a view steeped in a desire to categorize and control the narrative of the landscape and people. The meticulous detailing masks a lot of historical complexities, but the selection, presentation and depiction has huge importance regarding Catesby’s contribution to racial, gendered, colonial and social power structures. Editor: Look at the delicate rendering of the scales, versus the smooth flat background. It makes one think about access to both resources and technology – not just on the artist’s part, but those of the labourers reproducing the prints. How are these visual elements conveying control of raw materials, and a system of manufacture that's rooted in social power. Curator: These images reinforced Europe's sense of intellectual dominance while often erasing the expertise and experiences of Indigenous communities in how knowledge was developed, utilized, circulated and credited at that time. It speaks volumes about the role of imagery in colonial projects. Editor: Examining those early processes of making is vital; it demonstrates an intense investment of labour that both reflects and obscures social disparities through time. This perspective reveals underlying complexities that challenge romantic or simplistic interpretations of early naturalism, connecting art directly with society's fundamental means. Curator: Right, we need to view these not merely as scientific documents but cultural artifacts deeply entangled with complex power structures. Editor: Yes, and to continue analyzing these works through this intersectional approach. This reveals art as something rooted in labour, commerce, and social narrative production.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.