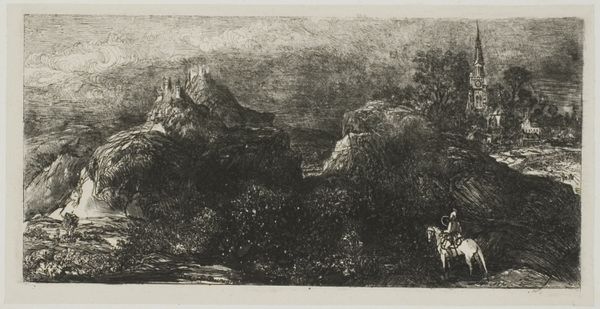

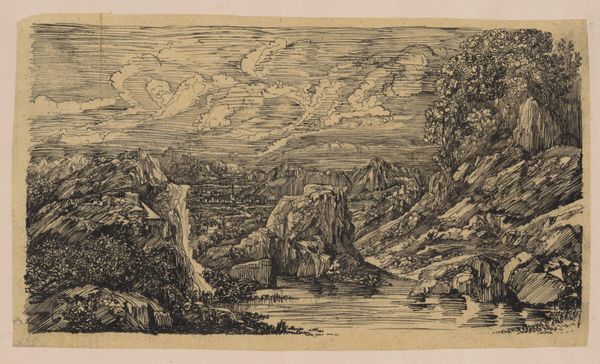

Dimensions: image: 9.9 x 18.2 cm (3 7/8 x 7 3/16 in.) sheet: 22.6 x 31.6 cm (8 7/8 x 12 7/16 in.)

Copyright: National Gallery of Art: CC0 1.0

Editor: This etching is "Cite Lointaine," or "Distant City," created in 1868 by Rodolphe Bresdin. It's teeming with detail, almost overwhelming at first glance. There’s this intense contrast between the dark, craggy landscape in the foreground and what appears to be a shimmering city in the distance. What do you see in this piece? Curator: I see a powerful commentary on isolation and the unattainable. Bresdin, living through a period of immense social upheaval in France, crafts a world where the promise of civilization—that "distant city"—is perpetually out of reach, obscured by a wilderness that seems to close in on itself. The etching itself, a painstaking and meticulous process, speaks to the artist's own labor, perhaps mirroring the societal pressures felt by many at the time. Notice how the landscape is not idyllic but almost hostile? Editor: Yes, there's a real sense of unease. Almost claustrophobic, even with that open space in the middle. Is that intended to reflect societal anxieties? Curator: Precisely. Consider the context: The rise of industrialization, the increasing divide between urban and rural life, the very real anxieties surrounding class and social mobility. Bresdin uses the Romantic landscape tradition, but subverts it. Rather than a celebration of nature's grandeur, we get a vision of nature as an obstacle, a barrier between the individual and the supposed progress represented by the distant city. What power structures do you see reflected in this imagery? Editor: I suppose the city represents opportunity and advancement, available only to some and at a distance for most others, shrouded by environmental and societal roadblocks? It does seem to be critical of established powers and idealized notions. Curator: Absolutely. Bresdin gives us a lens through which to view not just the physical landscape, but the sociopolitical one as well, inviting us to question the narratives of progress that often mask deeper inequalities. Editor: That's really interesting. I initially just saw a complex landscape, but framing it within that social context gives it so much more depth. Curator: Exactly, art doesn’t exist in a vacuum. It is informed by and responds to the social, political, and economic realities of its time. Recognizing that allows us to have a much richer understanding of any given work of art.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.