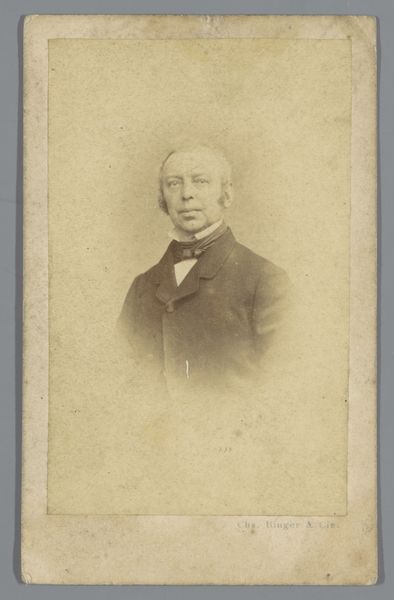

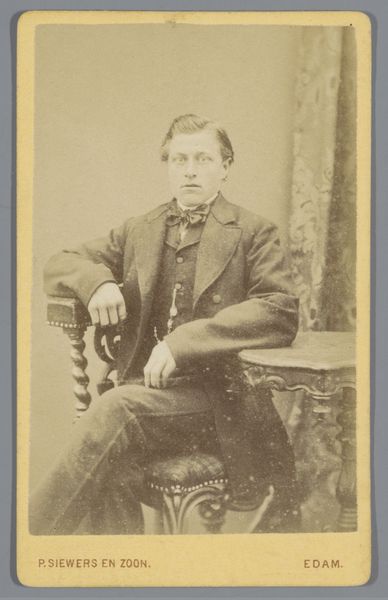

paper, photography, gelatin-silver-print

#

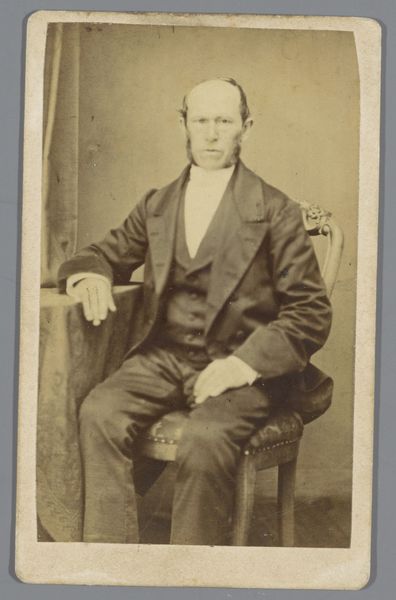

portrait

#

paper

#

photography

#

historical fashion

#

gelatin-silver-print

#

paper medium

#

realism

Dimensions: height 105 mm, width 63 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Oh, there’s something quite haunting about this portrait. Editor: Yes, isn't it fascinating? We're looking at "Portret van een onbekende man," or "Portrait of an Unknown Man," created by Pieter Siewers sometime between 1857 and 1898. It's a gelatin-silver print on paper. The sepia tones lend a melancholy feel. Curator: Absolutely. The tones and the man’s reserved posture – a strange mix of solemnity and vulnerability, as if the camera has stolen a piece of his soul. And to think this image survives; paper, chemicals, time all working together to leave him for us, gazing steadily. What do you make of that heavy woolen coat, from the perspective of production? Editor: The materiality is key. Think of the processes involved! Siewers meticulously coating the paper, exposing the image in the darkroom… Even the specific clothes denote social status, wealth probably connected to some degree of land ownership. Photography itself was a rising commodity, a democratizing technology in that sense. Making portraits more widely accessible, although even obtaining simple paper prints may still have meant financial outlay. Curator: I love that democratizing aspect. For years, portraits were limited to the wealthy, rendered in paint with a flattering eye. This... this is arguably closer to a real person. He's staring directly, almost defiantly. Not idealized. Though I do wonder, did Siewers retouch these? Even early photographs often had that hand-done alteration after the printing process, to subtly refine. Editor: Very possibly so, which muddles the authenticity further, doesn't it? Although such acts also imply how highly this society viewed aesthetic improvements to represent themselves. Still, the relatively raw quality brings us close to the physical, and maybe that offers new ways into seeing history, not through paintings hung on gallery walls so much as printed media accessible to all. And maybe the slight imperfections capture some true qualities the high art excludes? The human flaws they wanted edited or glossed? Curator: Perhaps. It's strange to ponder that he never imagined being scrutinized so intensely centuries later. Does the fact that we don't know his name somehow change the viewing experience? Give the picture a different weight, considering these images and techniques as art. Editor: The anonymity allows projection, doesn't it? He becomes Everyman. We can overlay narratives of labour, loss, change with the industrial era upon his neutral gaze. His unknowability opens possibilities. Curator: A ghost of a man, captured in silver and gelatin. Poignant, really. Editor: Agreed, and a document ripe for understanding labour and consumption within photographic creation.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.