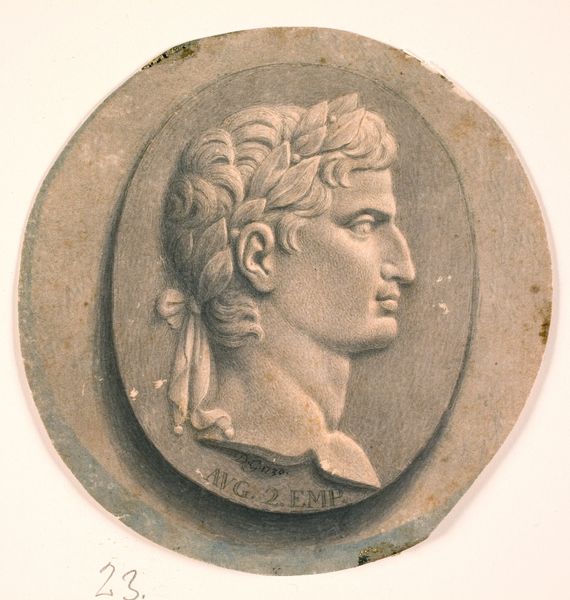

drawing, charcoal

#

portrait

#

drawing

#

sculpture

#

greek-and-roman-art

#

ancient-mediterranean

#

charcoal

#

charcoal

Dimensions: 116 mm (None) (None)

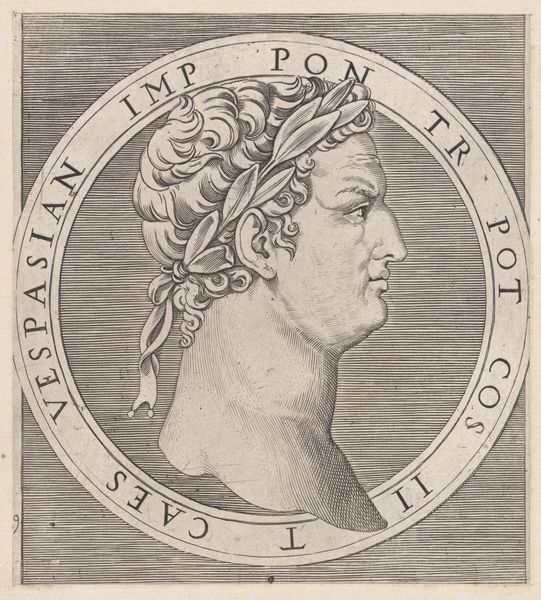

Curator: Here we have Didrich Gercken's "Portrætmedaillon af Titus Vespianus. Romersk kejser," rendered in charcoal around 1725. Editor: Immediately, the coolness strikes me. The muted grays evoke a certain stoicism, a deliberate removal from the passions of the moment. The laurel wreath, however, does create a symbolic link with the glory days of the Roman Empire. Curator: Exactly! The laurel wreath, a classic symbol, denotes victory, honor. Think of it as Gercken participating in a long lineage of artists reaching back to antiquity, visually cementing Titus within that cultural memory. Editor: But who gets remembered, and how? Titus was a relatively short-reigning emperor. It’s curious to see him singled out for such memorialization. We need to consider what projecting this image of power—of *Roman* power, specifically—achieved in Gercken's time. This wasn't simply an objective portrayal. It served a cultural function. Curator: Agreed. The continuity it evokes—Roman ideals passed down and visually re-articulated through the ages. Think of the Renaissance fascination with classical antiquity, and how those artists likewise used symbolic visual language to elevate patrons, or signal renewed societal values. It’s an idealized form; one we project significance onto. The power and symbolism from one period get grafted onto another. Editor: That idealization smooths over the complexities of history. By focusing on the visual cues of authority, we can ignore that even "good" emperors like Titus presided over systems of inequality and subjugation. He represents an establishment—it is vital to remember this. Curator: An establishment which clearly understood how critical its own image would be across time. How telling it is that an artist centuries later would look back to a figure like Titus and find him worthy of emulation. It underscores that powerful archetypes continue to reverberate, even when the specific histories become less clearly defined. Editor: I wonder, looking at it now, what our present will look like in centuries hence. Whose portraits will carry the weight of symbolic representation, and how will our age be interpreted through their faces? Curator: I suspect some portraits currently unseen in museums, the faces of individuals that don't neatly fit with our established historical narratives, may offer an eye-opening perspective.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.