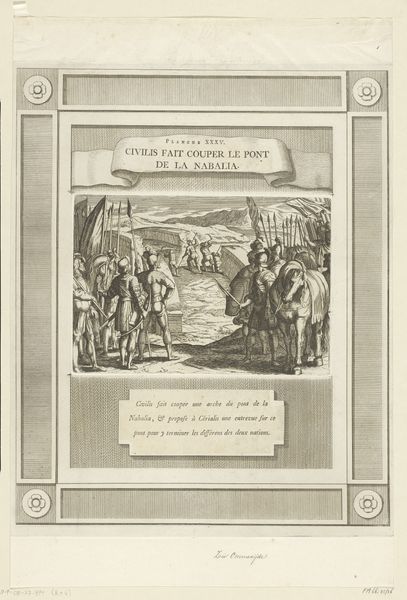

Dimensions: height 140 mm, width 202 mm, height 370 mm, width 300 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

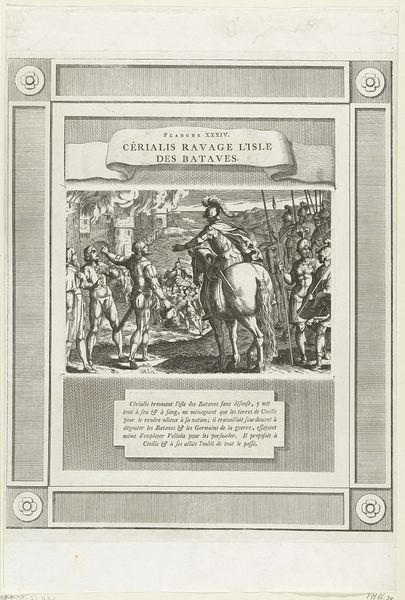

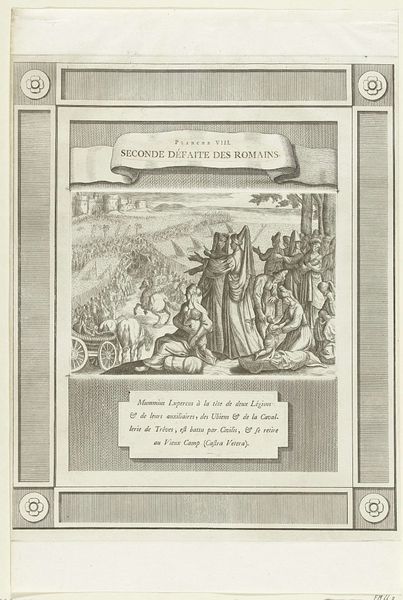

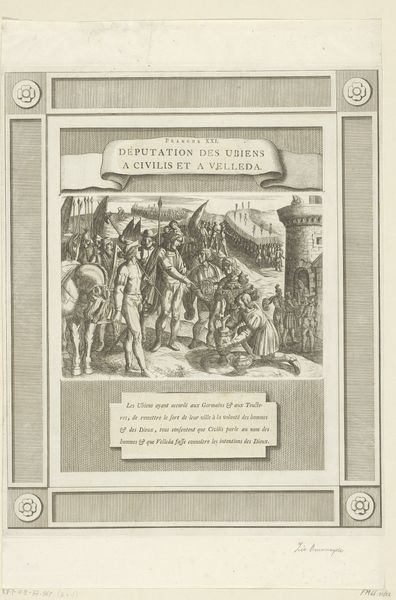

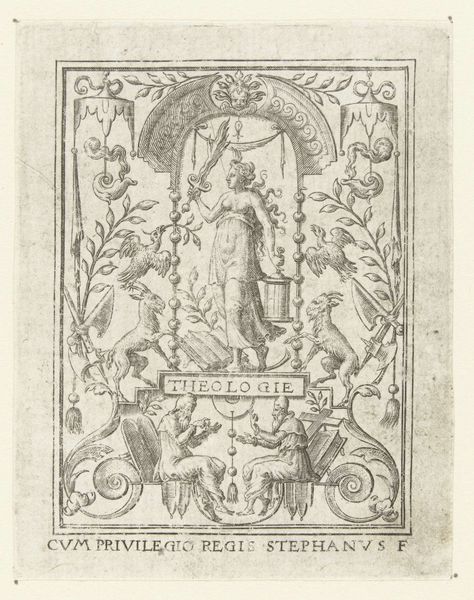

Curator: This engraving, "Titelprent voor de serie De Bataafse Opstand, 69-70," dating from 1768 to 1770, offers an allegorical view on the Batavian revolt. Editor: It feels overtly staged. Two figures meet amidst carnage; there is an almost propagandistic element in trying to convey harmony emerging out of visible and obvious destruction. Curator: Absolutely, considering its production in the late 18th century, we see a specific interpretation of a historical event, meant to instill a sense of national pride in the Dutch identity while also grappling with the complex power dynamics of that time. Editor: Tell me about the process. The line work suggests meticulous planning, yet the image’s texture, the material density that evokes social hierarchy, almost buries its classical-realism qualities. Was it destined to be viewed by many, or created for a limited circle? Curator: Given it’s a print consisting of engraving and etching, and given its place within a series held at the Rijksmuseum, this was probably designed for wider dissemination than a singular painting commissioned for private display. However, access would still have been restricted to those with literacy and a certain degree of financial stability. Editor: It makes sense to me. You see the clear intention here is to mediate memory through accessible materials. By circulating an image rooted in classical style, with an appeal to a very select population, what sort of cultural agency do you think these artists were trying to elicit? Curator: A relevant point. Considering the social upheaval occurring around that time in the Western world, artists perhaps felt driven to connect historical resistance with a desire to be seen on an equal footing on the European stage, or to be seen and recognized, not least, as free from subjugation. The Batavians almost become a stand-in for the Dutch. Editor: As a tool of ideological framing, the print makes accessible a wider narrative; an origin story constructed through labor and designed for collective consumption. The materiality provides avenues into exploring 18th-century Dutch national identity in complex ways. Curator: Agreed. Thinking about intersectionality here – race, class, gender – this image becomes so telling about who gets to participate in constructing and consuming national narratives, but also who is absent, either dead on the ground in the foreground, or excluded entirely from the story of a people. Editor: A fruitful reading for such a densely constructed historical interpretation. It calls on us to be inquisitive when understanding what it is that is presented, and perhaps more urgently, what’s excluded.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.