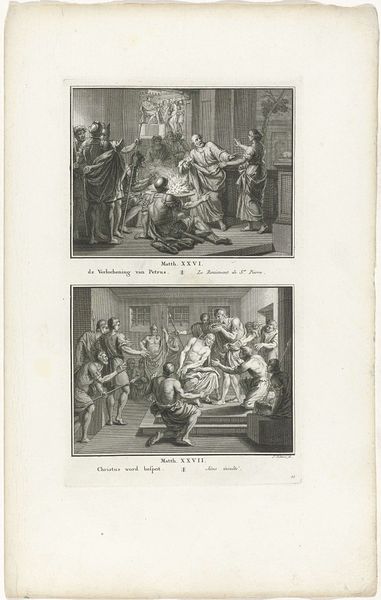

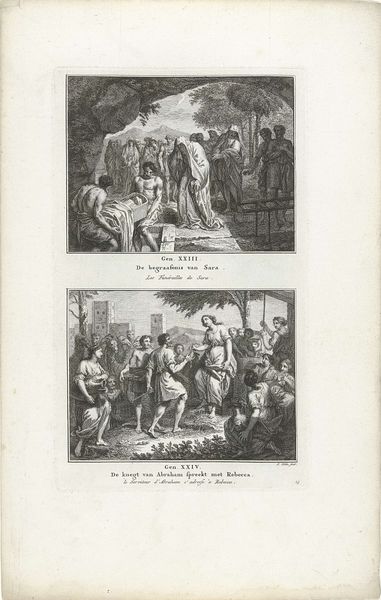

Geseling van Christus en Christus aan het volk getoond (Ecce homo) 1791

0:00

0:00

jacobfolkema

Rijksmuseum

Dimensions: height 321 mm, width 189 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

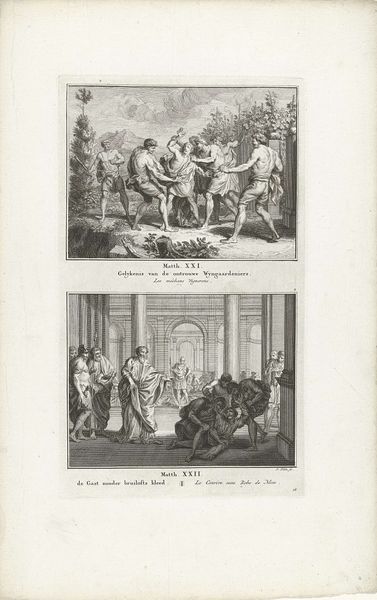

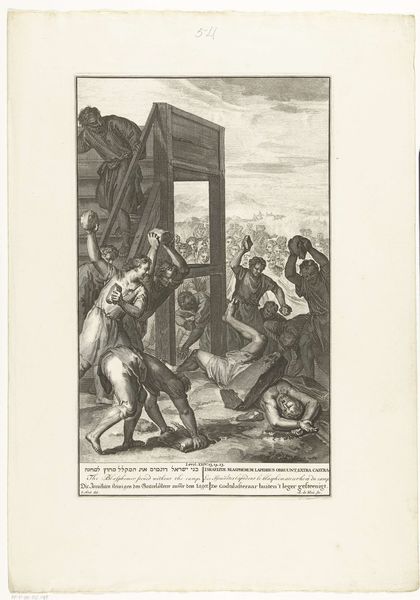

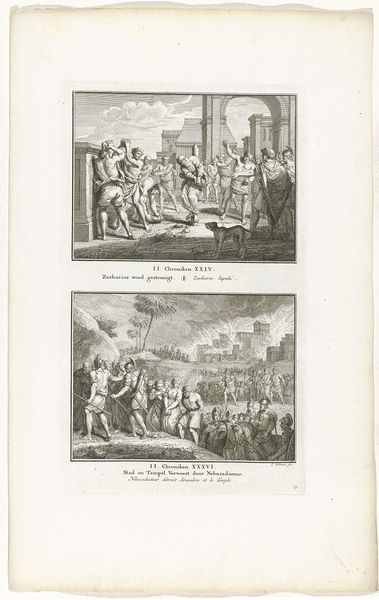

Curator: This print, "Geseling van Christus en Christus aan het volk getoond (Ecce homo)" dating back to 1791, is currently held at the Rijksmuseum, and made by Jacob Folkema. Editor: The starkness is what hits me first—the way the white of the paper highlights the scenes of suffering. There’s an unsettling calm to it, given the subject matter. Curator: These two images, arranged vertically, are both steeped in historical narrative—and potent displays of power. At the top, the flagellation, and at the bottom, Christ presented to the people. It begs the question: how are power dynamics visualized and then disseminated via the materiality of print? Editor: Precisely. Look at the way the bodies are rendered with such detail despite being a print. The engraving lines, the labour invested by Folkema in recreating such brutality raises important ethical concerns. Where is the agency for Christ in this representation? The use of engraving itself as a medium, known for its capacity for reproducibility, underscores the repeated exploitation. Curator: The presentation of Christ, framed within classical architecture, invites comparison with historical power structures. I find it revealing that the artist positions Christ relative to themes of injustice and the corruption that seeps from positions of power in socio-political spheres. Editor: The texture of the architecture against the relatively smooth rendering of skin is so striking; the contrast serves to elevate the brutality, perhaps suggesting that it is institutional and even integral to the world around him. The print serves to remind us how easily the image of suffering is made into a commodity, ready for mass consumption. Curator: Right. This really makes me consider how these historical portrayals of subjugation contribute to our contemporary understanding—and perhaps our acceptance—of power imbalances today. Editor: Definitely. Reflecting on Folkema’s processes allows us to challenge assumptions about both artistic labour, production, and the nature of the society from which the image sprung.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.