Dimensions: 15 x 22 1/4 in. (38.1 x 56.5 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

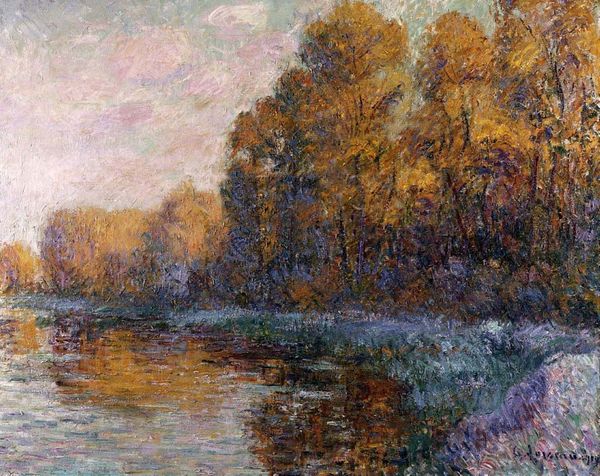

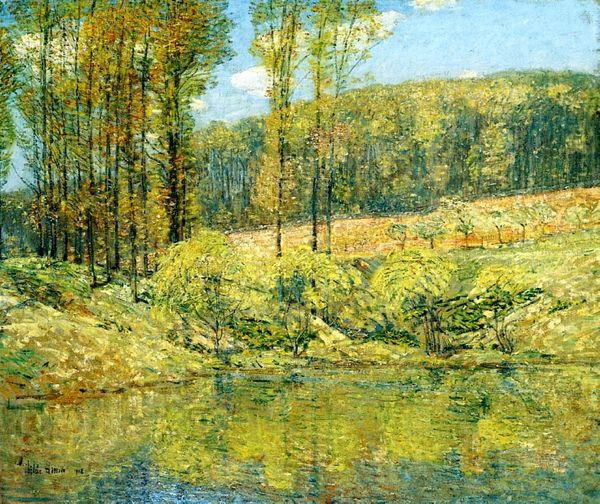

Curator: This is William Stanley Haseltine's "Mill Dam in Traunstein," painted in 1894, a delicate watercolor currently residing at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Editor: It strikes me immediately as an invitation—the hazy light, the gentle bend in the river... it's deeply atmospheric. Curator: Notice how the colors operate? The bright autumnal foliage seems almost to echo the past; in contrast with the calm blue stream. The season here feels very significant. Editor: I'm interested in that "calm blue stream" itself. It is anything but calm; its color hints at possible pollutants due to factory waste. What industrial processes occurred upstream from the Mill Dam at this time? The means of the water-powered production in the area should influence this discussion. Curator: True, the rise of industrialization in late 19th-century Europe undeniably shapes our understanding. And speaking of water: it's used here in the method of creating this art. It has a double significance: as subject and material. This watercolor technique captures the mood perfectly. Think of its fragility, how readily pigment spreads and blurs when working *en plein air*. It echoes the transient nature of time as perceived in the landscape. Editor: It's this idea of transient beauty that strikes me as a little misleading, especially if he chose the watercolour method purely due to convention. Watercolours may allow artists to quickly create art in open-air, however, their beauty might not last. It's important for a viewer to consider its longevity and the resources that had to go into producing it, even with the watercolor method, that go well beyond capturing an idyllic image. The mill produced product and generated refuse and waste. The artist here omitted this aspect of that society for the "beauty" of a landscape. I think its history matters in the present. Curator: Perhaps then Haseltine's selection, of materials speaks to both preservation, of process, and something already on its way to vanishing in memory or place? The "beauty," is a lament for something that cannot stay or an ignorant refusal of acknowledging its place within a history. Editor: So, what does persist is not an image, but what caused it to need immortalization on the page through the means that society demanded for consumption: a purchased experience mediated by ignoring any negative impacts. It forces the viewer to see that materials are the evidence of power relations that should always stay at the forefront. Curator: Food for thought; an idyllic scene holding a more complex reality. Editor: Always an element, however concealed or elided, is necessary for reflection and engagement.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.