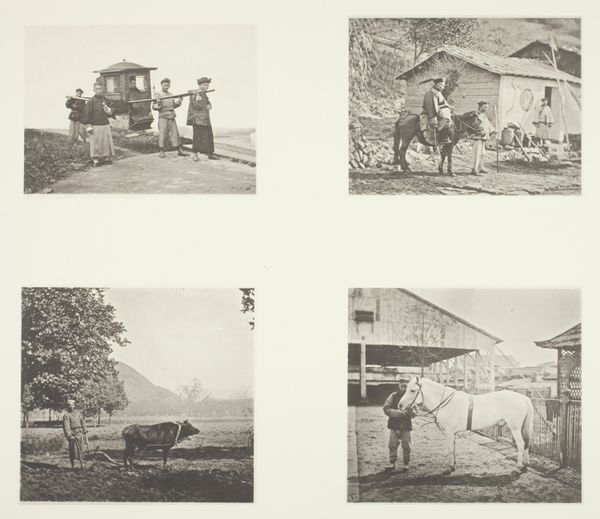

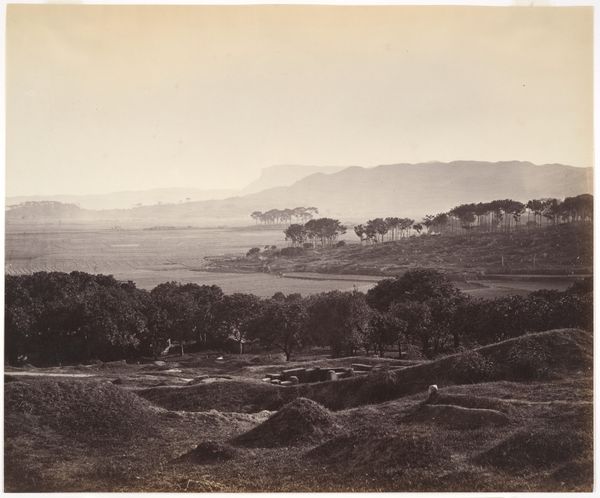

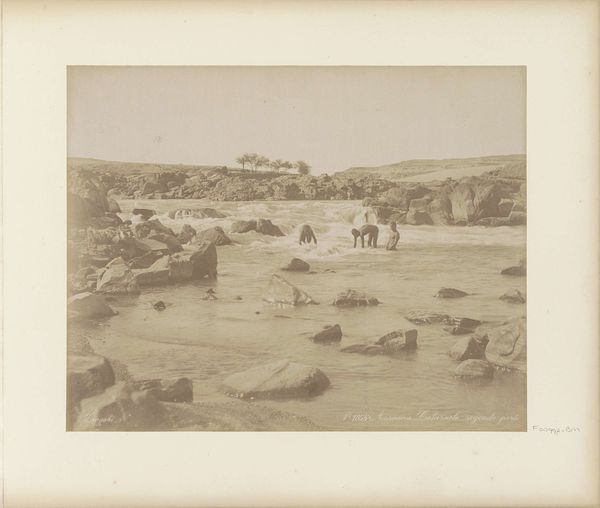

The Tea Plant; The Tea Plant; Yenping Rapids; A Small Rapid Boat c. 1868

0:00

0:00

photography

#

16_19th-century

#

asian-art

#

landscape

#

photography

#

monochrome photography

#

realism

#

monochrome

Dimensions: 10.9 × 12.3 cm (upper left image); 10.9 ×12.2 cm (upper right image); 11.4 × 12.3 cm (lower left image); 10.9 × 12.3 cm (lower right image); 34.7 × 47.2 cm (album page)

Copyright: Public Domain

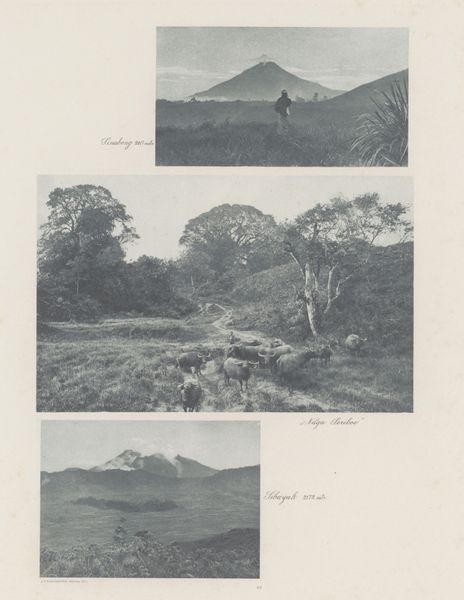

Curator: This work is titled "The Tea Plant; The Tea Plant; Yenping Rapids; A Small Rapid Boat," a photographic album page by John Thomson, created around 1868. The collection is held here at the Art Institute of Chicago. My immediate impression is its quiet, observant nature; it feels remarkably balanced. Editor: Indeed. The way Thomson organizes these four separate images within a single frame creates a visual poem about labor, landscape, and the flows of production in 19th-century China. Look at how the top two photographs show the careful cultivation of tea, and the lower two capture its transport by water. Curator: Precisely. The composition utilizes a straightforward grid, yet there’s a rhythmic contrast between the static tea plants and the dynamic, rapid waters. The monochrome tonality further unifies the elements, underscoring a serene yet industrious quality. What I find most striking is how Thomson utilizes light and shadow to sculpt depth. Editor: Right. That light reveals much about the labor embedded in tea production and river transportation. The photographic process itself – the chemicals, the equipment, the time spent in these remote areas – represents a significant investment of labor and resources. Curator: Consider how these seemingly detached scenes imply an underlying narrative. The diagonal thrust of the rapids is offset by the solid forms of the mountains and dwellings. There’s a clear formal interplay at work between stability and flux. Editor: I am curious about the perspective Thomson employs. His positioning seems to elevate the tea cultivation as a sort of objective observation, while those involved with the river become pieces of it, not separate from nature. I see the colonial gaze implied in those artistic decisions, which in turn speaks of larger trade mechanics at play during the late Qing dynasty. Curator: Perhaps it is that colonial gaze which renders such beautiful contrasts into something almost diagrammatic; a system seen from the outside. What this layout does so successfully is showcase how the land itself, cultivated by these labors, yields visual poetry. Editor: I'm drawn to thinking about how the tangible conditions of Thomson’s photography reveal social hierarchies in 19th century China. Examining the entire lifecycle through his images, a flow is represented and the value chain becomes transparent to those in another place and time. Curator: Thinking through those ideas highlights for me how his composition emphasizes the human connection with both the land and the currents of economic exchange at that time. Editor: For me, that focus reminds us how every element within art—like any production or extraction process—is deeply entrenched in both social relations and labor.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.