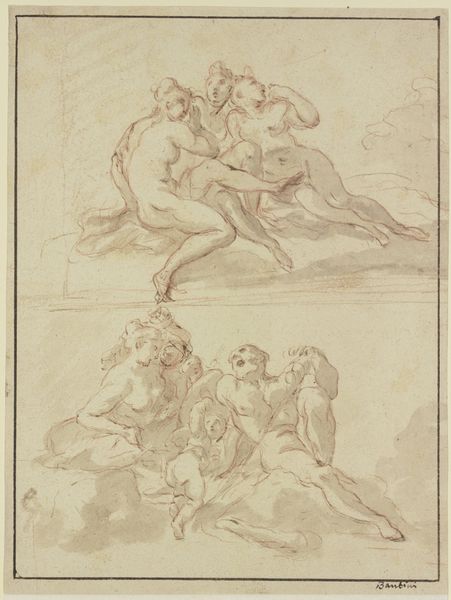

drawing, paper, ink, pencil

#

portrait

#

drawing

#

imaginative character sketch

#

light pencil work

#

self-portrait

#

quirky sketch

#

pencil sketch

#

mannerism

#

figuration

#

paper

#

personal sketchbook

#

ink

#

sketchwork

#

pencil

#

sketchbook drawing

#

genre-painting

#

storyboard and sketchbook work

#

italian-renaissance

#

nude

#

sketchbook art

#

fantasy sketch

Dimensions: height 133 mm, width 154 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: It feels very immediate, almost intimate, seeing these figures sketched in ink and pencil. There’s a rawness here. Editor: Indeed. What we’re looking at is entitled “Studies van vrouwelijke naaktfiguren,” or Studies of Female Nudes, attributed to Cornelis van Poelenburch, likely created sometime between 1600 and 1667. It's currently held in the collection of the Rijksmuseum. Curator: Attributed, you say? I wonder what this suggests about the artist’s standing and perhaps what his artistic labour was worth if his pieces went uncredited? I also get a distinct Italian Renaissance feel to it, that idealized, yet slightly off, figuration. Editor: It absolutely gestures toward the Italian Renaissance. Van Poelenburch did, in fact, spend a significant time in Italy and was certainly influenced by it. This work showcases a fascination with classical forms, but filtered through his own artistic sensibility. It’s interesting to note that the Italian Renaissance, particularly in Florence, really codified and codified what "high art" even *meant,* emphasizing skill and intellectual ambition in ways that previously commingled with craft. Curator: Do you see a difference, though, between his sketches and those made during the Italian Renaissance itself? How do you think Poelenburch engaged with that legacy, knowing full well the immense shadow those masters cast? Editor: That's a crucial question! I think the key here is access. The Renaissance masters were creating imagery deeply embedded in a courtly culture, where they functioned as status symbols as well as works of devotional or allegorical significance. Van Poelenburch's time presented the rising merchant class; artwork became a thing on the market, in a new social milieu and market forces changed everything, the production as much as the imagery. Curator: Absolutely. This wasn’t art made for Medicis, but to be sold to less elevated collectors, for burghers trying to project their rise in status. And speaking of market demands, one imagines nude studies always being quite sought-after! It makes one wonder about the process: did he have access to live models or was this from memory? I feel as if these are not exactly true-to-life... Editor: Indeed. It offers such insight into artistic production at the time. Seeing all these forms presented together opens a lens onto his studio practice itself. I am now thinking more deeply about how Dutch painting was produced in workshops to fulfil this new demand for art from this burgher class you spoke of. Thank you! Curator: The pleasure was mine. Examining process makes these pieces even more vibrant to me now.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.