photography, albumen-print

#

portrait

#

photography

#

historical photography

#

19th century

#

albumen-print

#

realism

Dimensions: height 83 mm, width 51 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

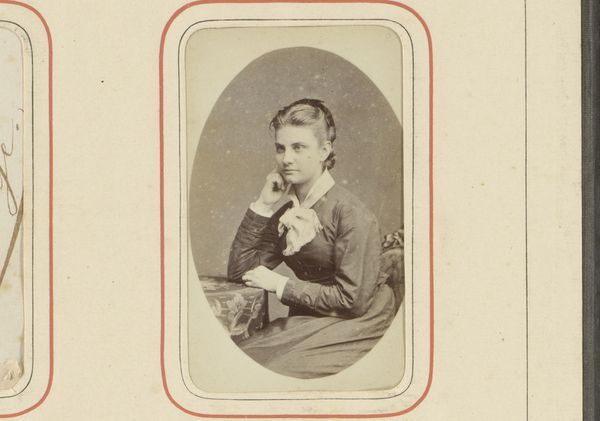

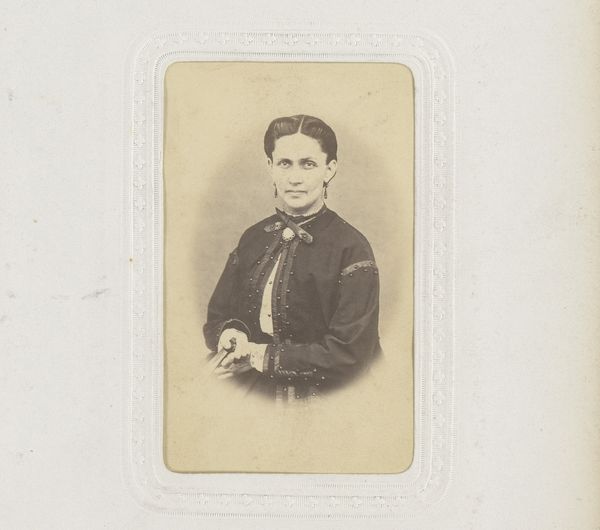

Curator: Here we have a portrait of a seated woman by Rosalie Sophie Sjöman, an albumen print, likely created between 1864 and 1900. What are your first impressions? Curator: It's quiet. The tones are muted, almost sepia-toned, and there is this tactile quality to the ruffled lace at her neck. You can almost feel its delicate texture, despite the smooth surface of the print itself. Curator: The history of photographic portraits in the 19th century tells us so much about social mobility and representation. Suddenly, capturing an individual likeness was democratized beyond the elite painting circles. Curator: Yes, and I'm also drawn to that democratization playing out materially. The albumen print process itself - using egg whites! It feels almost like a domestic craft elevating a commercial, studio practice. Curator: Exactly! Sjöman, as one of Sweden’s first professional female photographers, embodies that intersection. This portrait then isn’t just of *a* woman, but reflects broader access for women, both as subjects and makers within the professional sphere. How were women entering creative fields, navigating business? This piece brings up so many vital discussions. Curator: Agreed. Thinking of the labor, too, the physical production. Albumen printing was intense. Preparing the glass negatives, coating the paper... Each photograph represents hours of often unseen work in the darkroom, shaping not only the image but also economic access. Curator: Considering its historical moment, it raises questions around the performance of identity. How did one wish to be seen? Her expression is serious, even introspective. Her pose with arms crossed lends an air of reserved self-possession. It contrasts so strikingly with how many women were viewed and portrayed at the time. Curator: That pose definitely signifies status, though with such a seemingly simple setup. I also wonder about the back of that chair that’s holding her. I think about the hands that wove the textile or carved the wood. Who constructed her seat? What class status did they represent? And were they included or represented within Sjöman’s sphere? Curator: Examining photographs like these pulls back so many layers on identity, labor, representation and what access was being offered to a society in great transition, especially for women. It forces us to think intersectionally about who gets to participate, both in front of and behind the camera. Curator: Precisely. I’m also now seeing it almost as an artifact: the chemical processes and craft which were brought to bear to materialize this particular perspective, both personal and historical.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.