print, photography

#

aged paper

#

homemade paper

#

paperlike

# print

#

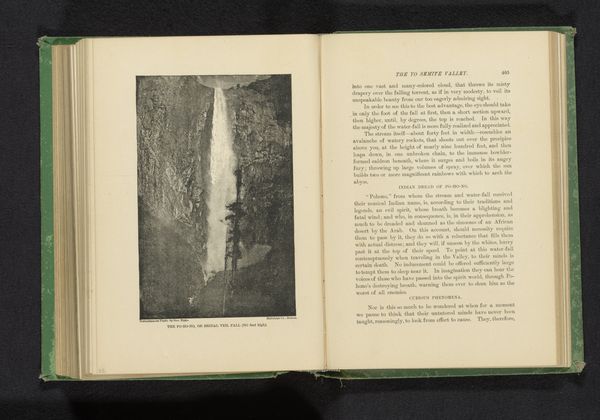

landscape

#

personal journal design

#

photography

#

thick font

#

handwritten font

#

delicate typography

#

thin font

#

historical font

#

small font

Dimensions: height 129 mm, width 193 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

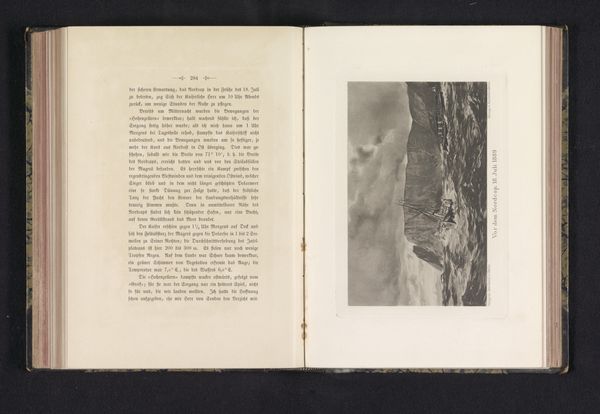

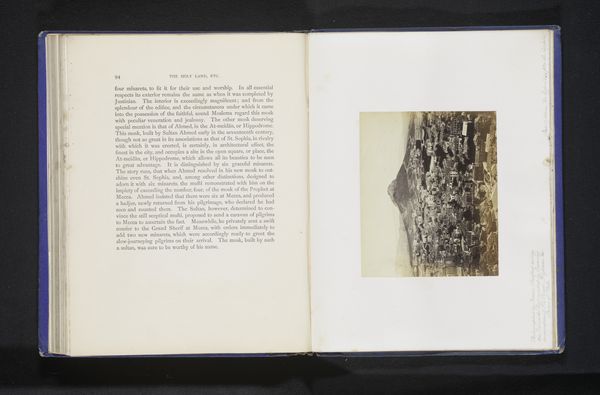

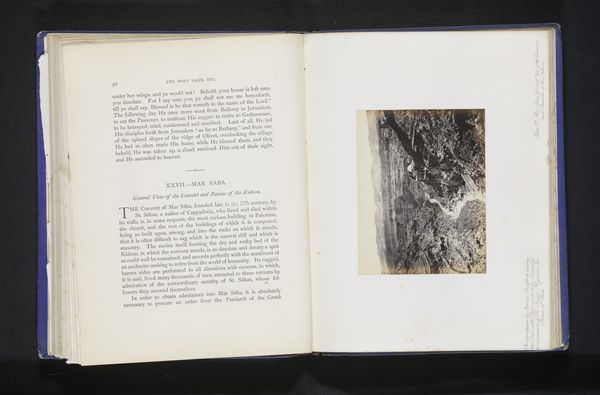

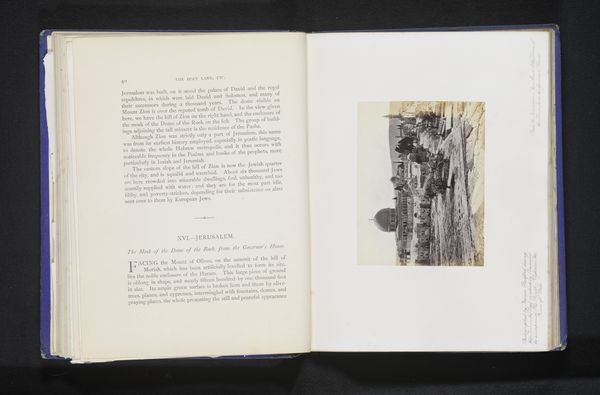

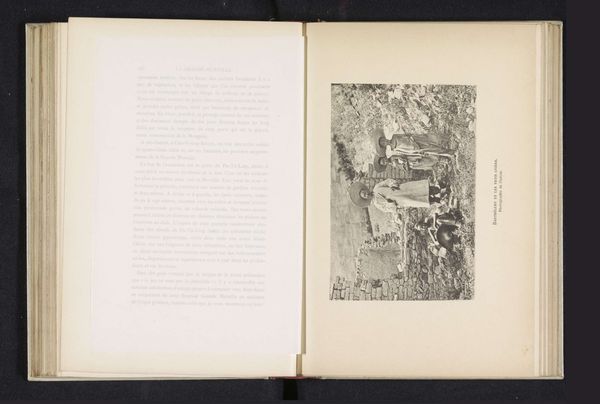

Curator: Welcome. We're standing before a print from 1869, entitled "Gezicht op Tasjkent," or "View of Tashkent." It appears to be a page extracted from a journal or perhaps a book. Editor: The texture immediately grabs me; you can almost feel the aged paper. The print has a raw, immediate quality—it looks like an unvarnished slice of life. There's a vulnerability in its directness. Curator: Indeed. The historical context is vital here. 1869, that's just a few years after Russia formally annexed Tashkent. This image likely served a very specific purpose—perhaps to document, legitimize, or even romanticize imperial expansion. Editor: It's interesting to think about whose view we're actually getting. This is supposedly a "View of Tashkent," but filtered, mediated, undoubtedly shaped by a colonial gaze. The composition, even its "slice of life" aesthetic, feels constructed, part of a narrative of power. Look at how the perspective minimizes local presence and emphasizes geography. Curator: That’s a astute point. We have to consider that photographs and prints were frequently used to create a sense of 'knowing' or 'possessing' a place, especially in the context of empire. The detailed linework allows a semblance of scientific accuracy—creating a believable vista. Editor: I'm also drawn to the people depicted. Their positioning and small scale reinforce that gaze and promote power imbalances. How might a person from Tashkent have depicted their home at that time, had they been allowed or empowered to do so? What stories remain unheard, overwritten? Curator: Exactly. This view becomes a document of power relations as much as geographical documentation. It invites critical consideration about access, control, and representation. The act of viewing is itself imbued with politics. Editor: Right. By acknowledging whose perspective is represented, we open up opportunities for alternative, critical perspectives to come forth. Looking through art is rarely a neutral activity, especially something so openly claiming to be a historical documentation. Curator: Examining “View of Tashkent” gives space for those larger questions concerning control, identity and seeing in a post-colonial age. Editor: It forces us to reckon with not only what is shown, but who gets to do the showing.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.