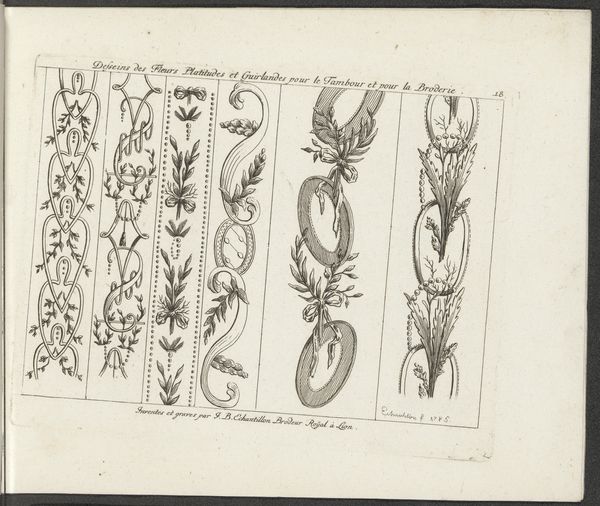

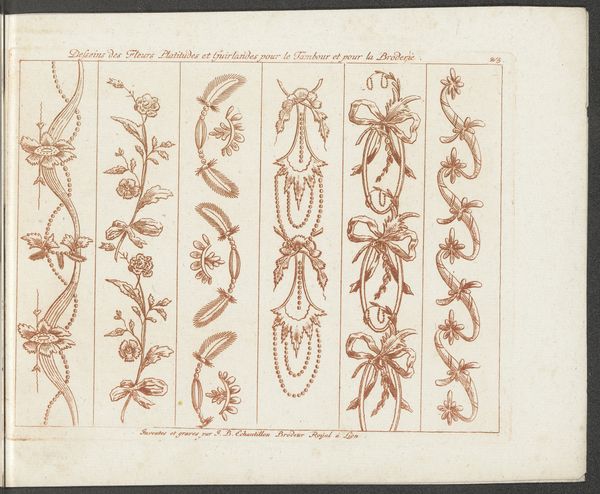

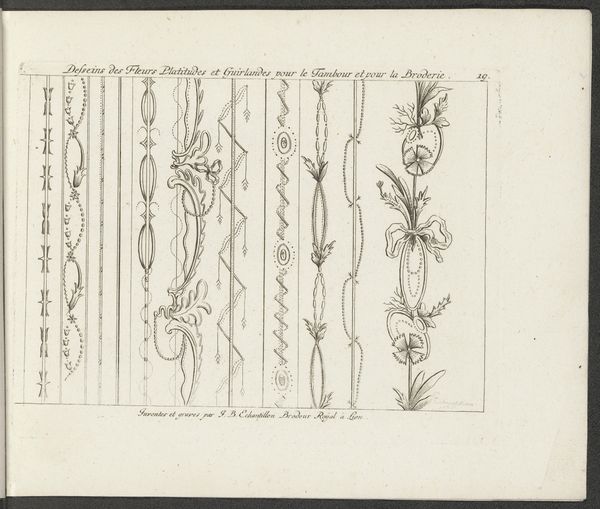

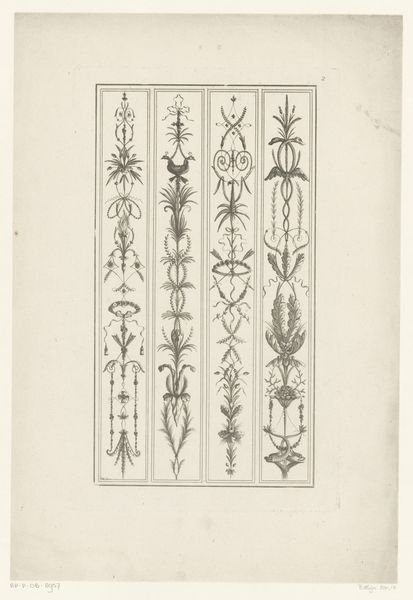

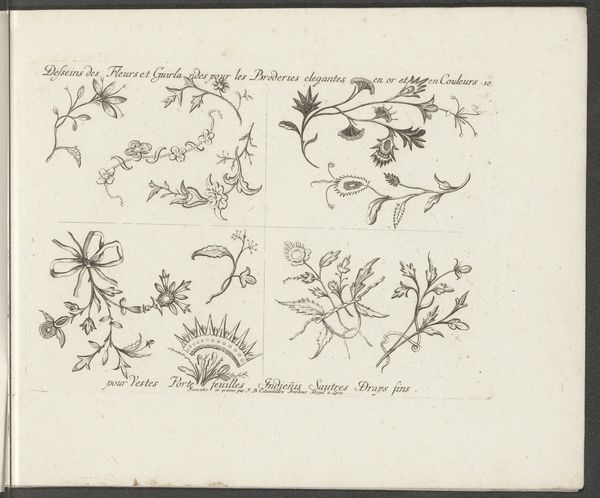

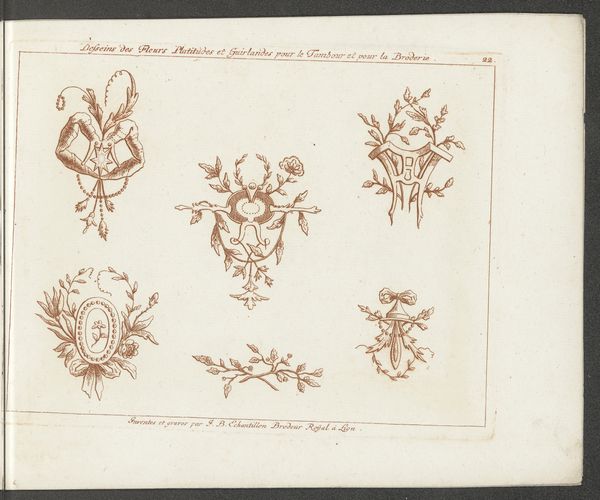

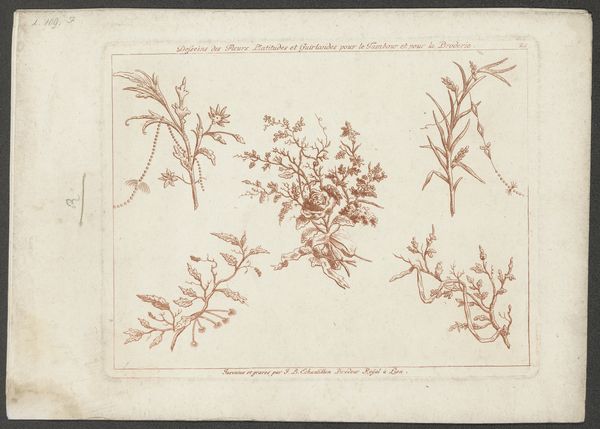

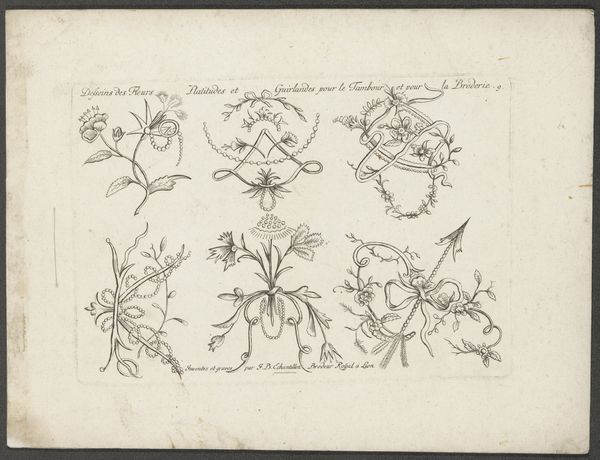

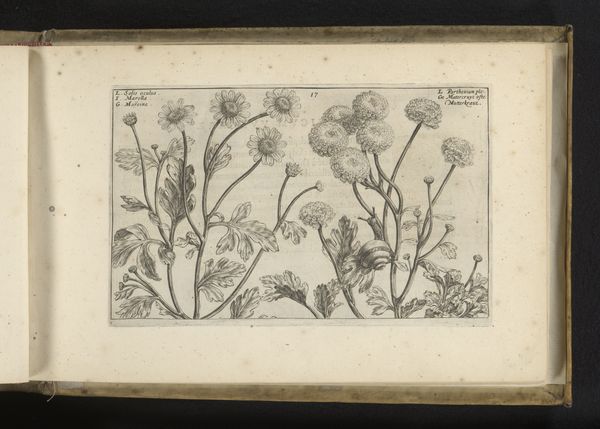

Dimensions: height 177 mm, width 229 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

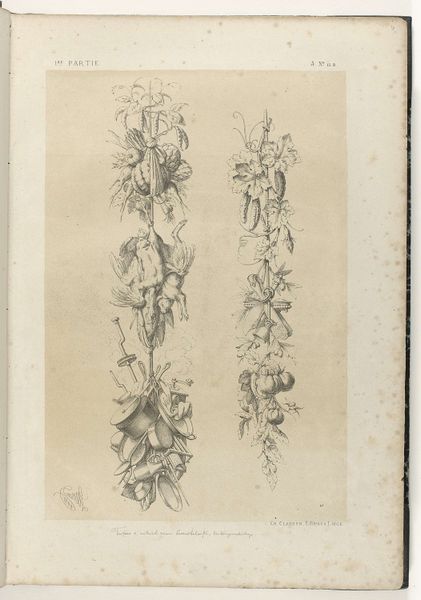

Curator: Looking at "Blad- en bloemmotieven en vlechtwerk," a drawing by Jean Baptiste Echantillon from 1785, presently residing at the Rijksmuseum, one is struck by its detailed floral and braided motifs, all rendered in ink on paper. Editor: My first thought is that this is exquisite. The line work is so delicate, it gives a real sense of depth and movement, doesn't it? Almost like watching plants sway gently. Curator: Precisely! Echantillon was designing patterns intended for tambour and embroidery. This speaks to a distinct connection between art, craft, and industry in the late 18th century. These patterns weren’t just aesthetically pleasing, they were templates for skilled artisans. Editor: Absolutely. It's fascinating how this one sheet gives us insights into labor practices and the decorative arts economy of the Rococo period. One might examine the implications of Royal patronage for artists and craftspeople like Echantillon. What socio-economic forces shaped this commission? Curator: That is relevant. These designs weren’t isolated artistic endeavors; they were integral components of a larger manufacturing and consumption cycle. Think about the availability of materials like paper and ink and who had access to embroidery embellished with these designs. Editor: Exactly. It's critical to remember that luxury goods weren’t equally available. Elaborate embroidery would signal the wearer’s status. Who had the economic freedom to commission works like these? The design reflects very specific social stratifications. The motifs feel controlled, refined—elements in a performance of power. Curator: And while Echantillon himself enjoyed royal recognition, we should still consider the gendered division of labor inherent in textile production at that time. Skilled embroiderers, often women, transformed these designs into material reality. What can the production of these sorts of materials tell us about preindustrial production? Editor: That tension—the artist’s recognized creativity versus the often-anonymous labor required to execute it—is vital. We get to examine class, skill, artistic innovation, and social context, all intertwined. Curator: Yes, understanding these works through material and social lenses can shift our appreciation away from purely aesthetic delight, encouraging us to explore their complex stories and significances. Editor: For me, that’s what truly makes art compelling—the chance to engage with historical complexities and think critically about the past's imprint on our present.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.