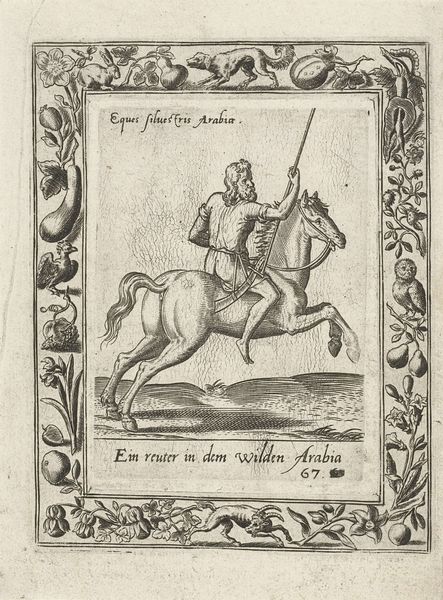

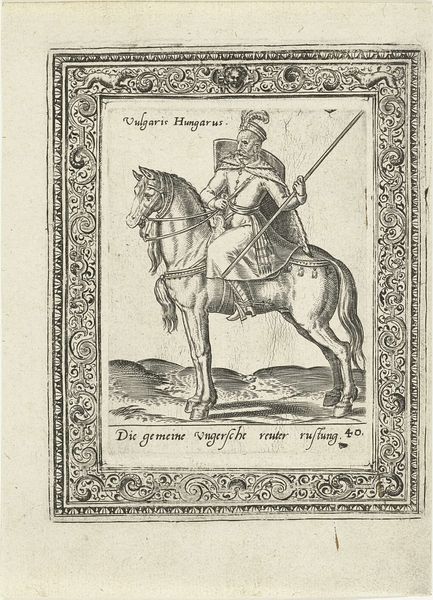

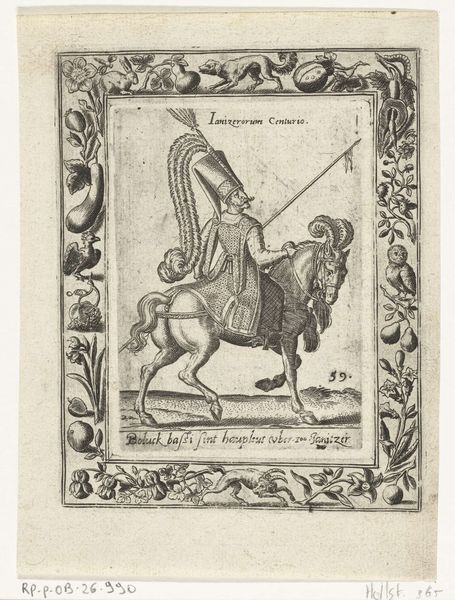

print, engraving

#

portrait

# print

#

pen sketch

#

old engraving style

#

figuration

#

form

#

11_renaissance

#

orientalism

#

line

#

genre-painting

#

history-painting

#

northern-renaissance

#

academic-art

#

engraving

#

realism

Dimensions: height 108 mm, width 74 mm, height 138 mm, width 108 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: This print, currently held in the Rijksmuseum collection, is entitled "Arabische hoofdman te paard", dating back to 1577. While the artist remains anonymous, its style certainly captures elements of both orientalism and the Northern Renaissance. Editor: First glance? It feels staged, doesn’t it? Like a tableau vivant, all carefully posed. The rider looks awfully stiff, like he is afraid to actually move on that horse! Curator: Absolutely. Consider the period. Such imagery served specific purposes. The "Arabische hoofdman" wasn't just a portrait; it functioned as a visual representation within a broader European understanding – or rather, misunderstanding – of the "Orient." The border surrounding the central image seems overflowing with symbols of exoticism. Editor: All those…gourds? What are they supposed to represent exactly? And are those supposed to be peacocks at the bottom of the print? Are they meant to evoke an abundant landscape or is this some coded language? Curator: Possibly both. Such detail often fed into the era's fascination with the "other." While exotic animals and fruits would imply richness and abundance, more generally it created this "otherness," that became an integral part of Renaissance visual culture. These elements often reinforced existing power structures and colonial narratives. Editor: So it is not really a snapshot, more like propaganda disguised as observation. But then, who *was* this Arab chief supposed to be anyway? An actual historical person or an archetype? And why Arabia? What’s the connection to the artist and, more generally, the audience? Curator: Excellent question! The "Arabische hoofdman" likely embodied a composite figure, not necessarily tied to a single individual. European interests in trade and political relations with the Arab world grew significantly during the 16th century. Representing him astride a horse could signify power and martial prowess – qualities that European audiences simultaneously admired and feared. Editor: The stiffness, the pose… it is as if this chieftain were deliberately frozen, captured as a trophy. I suppose we can never really escape the filters we put on the world, even when trying to depict "reality." It all tells us less about him, the man, and a great deal about the viewer, doesn't it? Curator: Precisely. By viewing this print critically, we gain insights into the historical gaze – the power dynamics and cultural assumptions that shaped how the world was perceived and represented during the Renaissance. Editor: I will leave with an echo then – it speaks less of a master horseman, but shows us much about the artist’s world – filtered and translated though, in ways that we must still unpack today.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.