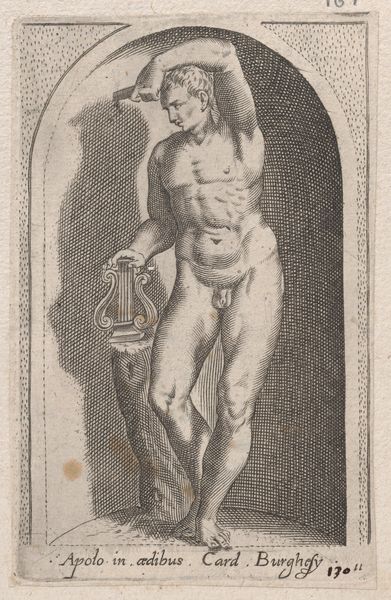

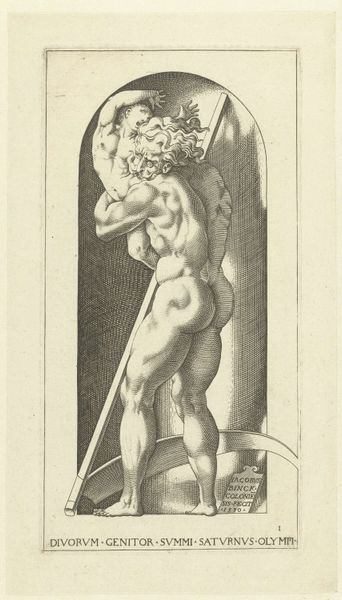

Speculum Romanae Magnificentiae: Apolinis (Apolinis in uiridario Magni Ducis Etruriae) 1530 - 1580

0:00

0:00

drawing, print, etching, engraving

#

drawing

# print

#

etching

#

mannerism

#

figuration

#

portrait drawing

#

history-painting

#

italian-renaissance

#

engraving

#

male-nude

Dimensions: sheet: 16 5/8 x 13 1/8 in. (42.3 x 33.3 cm) plate: 4 15/16 x 3 1/8 in. (12.5 x 8 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

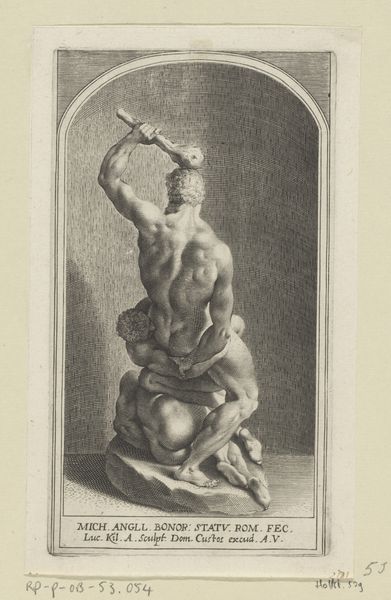

Curator: This engraving, made sometime between 1530 and 1580, bears the title "Speculum Romanae Magnificentiae: Apolinis (Apolinis in uiridario Magni Ducis Etruriae)". It’s part of the Speculum Romanae Magnificentiae, a collection showcasing Roman antiquities. The inscription suggests it depicts a statue of Apollo in the garden of the Grand Duke of Etruria. Editor: My initial feeling is one of understated power. There’s something almost vulnerable about Apollo, posed semi-nude and lost in his music, yet the heavy lines and the dominating figure give him an undeniable presence. Curator: Absolutely. The engraving circulated within a very specific economy. The "Speculum" served not just as art, but almost as a catalogue for artists and patrons. Consider its dissemination: engravings like these shaped perceptions and solidified the aesthetic vocabulary of the Renaissance, particularly in the orbit of powerful figures like the Duke. Editor: Right. And that vulnerability I mentioned becomes interesting within that context. Apollo is the god of music and light, but also healing and prophecy. To see him here, almost trapped within the rigidity of the engraving, the meticulous detail, and seated uncomfortably—it suggests that even gods are bound by mortal perception. It also echoes anxieties and celebrations around artistic skill: the flute’s potential is liberating, yet it is expressed in such highly constructed form. Curator: I think that interpretation holds weight. We should note the stylistic echoes of Mannerism – the almost exaggerated musculature, the stylized pose – they place Apollo within a framework of artificiality and cultivated display that defines artistic patronage during the Italian Renaissance. The print itself plays into the elite culture. Editor: Exactly. The flute itself! The symbolism is so ripe. Panpipes—representative of Arcadia, pastoral serenity, and the natural world are presented in concert with this sculpted physique, contained in art. The instrument then almost reads as the one thing closest to Apollo's divine core. It's humanity grappling with divinity. Curator: This artwork, and indeed this collection, makes visible the consumption of culture and knowledge that shaped Europe’s artistic identity, as well as demonstrating the socio-political weight that imagery can have. Editor: The beauty of it, isn't it? To glimpse the immortal, carefully packaged within layers of societal aspiration and artistic interpretation. I’m grateful to have taken a moment with this print.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.