Dimensions: height 172 mm, width 128 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

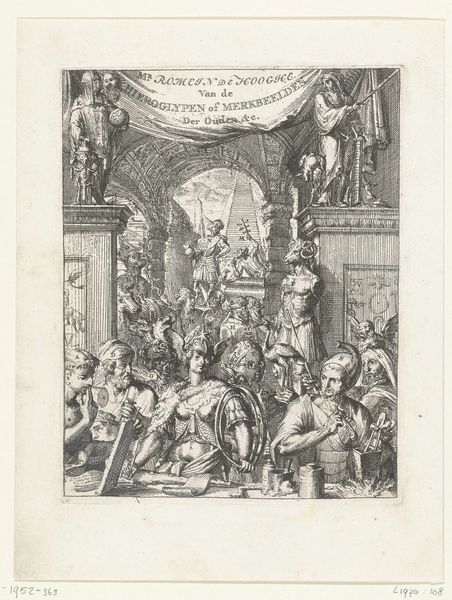

Curator: This engraving, dating from 1768, is titled "Briefschrijvende man onder toeziend oog van geestelijken" which translates to "Man writing a letter under the supervision of clergymen." It’s by Reinier Vinkeles, a Dutch artist known for his detailed historical scenes. Editor: Oh, wow, that's a lot to take in at once. My initial impression is just how... unsettling it is. The scene feels crowded and there's a kind of watchful tension in the air. I can feel the weight of the church breathing down that poor guy’s neck. Curator: Absolutely! The very process of engraving creates a sense of precision and control, which mirrors the control exerted by the clergymen over the writer. Notice the careful rendering of each line; it speaks volumes about the meticulous craftsmanship and time investment involved. These prints, reproduced en masse, would've brought Vinkeles both income and a voice to be reckoned with. Editor: Yes! It makes me think about the socio-economic context here. The piece acts like an exercise in visibility – showing labor, but also the instruments of labor: paper, ink, the printing press that disseminated this very image. There’s also those chubby cherubs wielding weapons in the lower register, I sense this piece acts as commentary of political power too. It's a battlefield in ink! Curator: Indeed, and while those cherubs appear almost whimsical, they could be seen as allegorical figures representing various factions or political entities involved in the history. In that respect it feels akin to looking through a kaleidoscope with a serious hangover. The religious and political power dynamic on full display! Editor: Looking at the material quality makes me consider this work as more than just a depiction of an historical scene. This act of mechanically reproducing art meant that new and more diverse groups of people could engage with these kinds of charged images. Each printed impression democratizing discourse… Curator: It becomes a dialogue, doesn't it? I initially felt only that tense pressure on the subject of the artwork, but considering how this piece reached the masses, I feel like the writer perhaps had the upper-hand after all. Editor: Exactly, through this image-making, even two centuries later, we continue to engage in the messy act of meaning-making and bearing witness.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.