tempera, print, photography

#

tempera

# print

#

asian-art

#

landscape

#

photography

#

ancient-mediterranean

Dimensions: height 228 mm, width 168 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

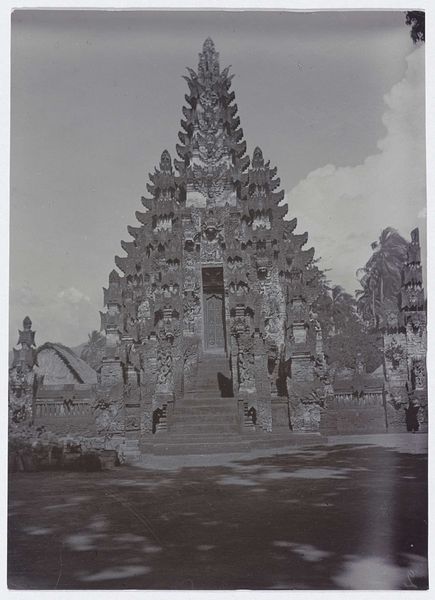

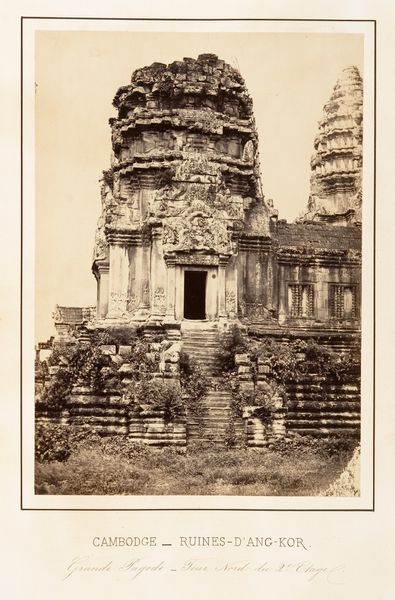

Curator: Immediately, the sheer density of carving strikes me; the tactile quality is overwhelming. Editor: Indeed. What we're looking at here is a photographic print, potentially tempera-enhanced, titled "Tempel in Bilabadjang, Bali, voormalig Nederlands-Indië," placing its creation roughly between 1890 and 1910 during the colonial period of the Dutch East Indies, as it was then known. Curator: So the image itself becomes part of that colonial project, documenting and, in a way, claiming ownership over Balinese culture through visual representation. The materiality of the print—the photographic paper, the potential addition of pigment— speaks to the means by which this 'exotic' scene was captured, processed, and disseminated back in Europe. It begs questions about the photographer's labor. Editor: And yet, what persists beyond the colonial lens is a powerful sense of spiritual presence. Consider the towering, pyramidal gateway, intricately carved with what appear to be protective deities and symbolic foliage. The stepped design directs the eye upwards, fostering a feeling of ascending towards the sacred. Curator: But what stories do the carvers' hands tell? Were they commissioned or conscripted, paid fairly or exploited? Who profits from this image? These questions must always accompany the aesthetic appreciation. What kind of access would they have to photography? The availability of material speaks to different audiences. Editor: I see layers upon layers of symbolism: figures perhaps drawn from Balinese Hindu cosmology meant to purify those who enter, transforming everyday experience into a sacred journey, maybe alluding to ancestral and natural veneration as a cultural narrative. The print becomes a palimpsest where those stories remain. Curator: But is "sacred journey" our interpretation, or theirs? The camera doesn't just record; it participates in shaping that perception. And the image, reproduced and circulated, becomes a commodity consumed within a colonial power dynamic. It shows me production in different layers. Editor: I concede the limitations of photographic documentation, but to me, it offers an echo of enduring Balinese cultural identity, communicated through enduring iconography and craftsmanship. I feel privileged for its preservation. Curator: Perhaps we find that by investigating its layers of materiality and the conditions that created that materiality we find ways of grappling with its past as an object and for Balinese people it endures now.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.