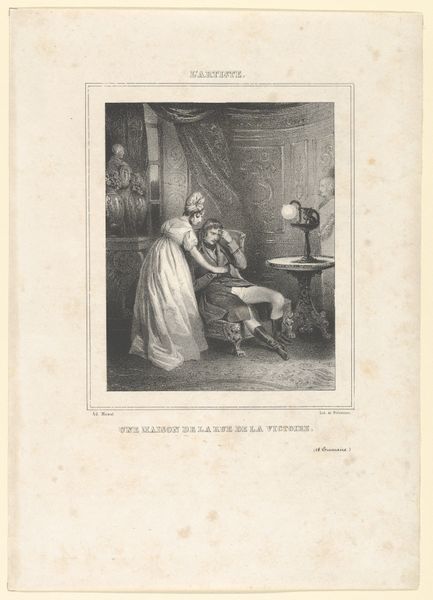

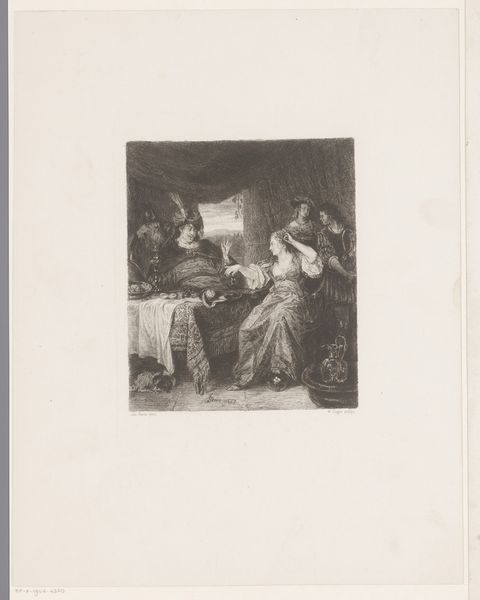

drawing, lithograph, print, paper, ink

#

portrait

#

drawing

#

light pencil work

#

lithograph

#

ink paper printed

# print

#

figuration

#

paper

#

ink

#

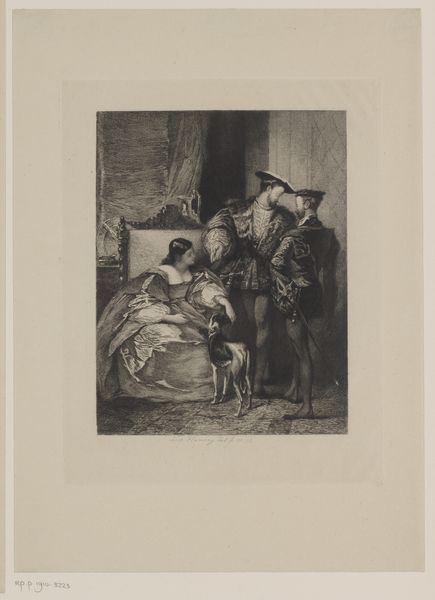

romanticism

#

france

#

history-painting

Dimensions: 242 × 198 mm (image); 548 × 360 mm (sheet)

Copyright: Public Domain

Editor: So, here we have Eugène Delacroix’s lithograph, "Hamlet and Ophelia, plate 5 from Hamlet," created between 1835 and 1843. It strikes me as quite a dramatic piece. I'm curious, what stands out to you when you look at it? Curator: Well, let’s think about the printmaking process itself. The lines, etched and transferred onto paper, represent a democratization of art, don't they? Instead of a unique painting, Delacroix produced multiples, expanding access to this scene from Hamlet. How do you see the social implications of that? Editor: That's fascinating! I hadn't considered the production aspect so directly. Does the choice of lithography—compared to, say, painting—affect how we perceive the emotional weight of the scene? Curator: Absolutely. The repeatable nature challenges the preciousness associated with singular artworks. Think about the distribution channels, too. Prints like these would circulate amongst a burgeoning middle class, shaping their understanding of art and literature, and Shakespeare, too. What does this availability do to our understanding of Romanticism? Editor: So, the emotional intensity remains, but the meaning becomes tied to its wider circulation and consumption, shifting the focus away from pure artistic genius. I see how this makes Delacroix’s Hamlet much more of a cultural artifact. Curator: Precisely. The raw materials – the ink, the paper, the printing press – become active participants in creating meaning, revealing art's deep connection to the material conditions of its creation and reception. Thanks for pointing that out. Editor: This was really interesting; I feel I look at artworks with another set of eyes now. Curator: Me too. It’s fascinating to reconsider artworks with that focus on process, labor and the materials, which certainly enriched my point of view.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.