#

aged paper

#

photo restoration

#

parchment

#

old engraving style

#

historical photography

#

old-timey

#

yellow element

#

19th century

#

golden font

#

yellow accent

Dimensions: height 85 mm, width 52 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

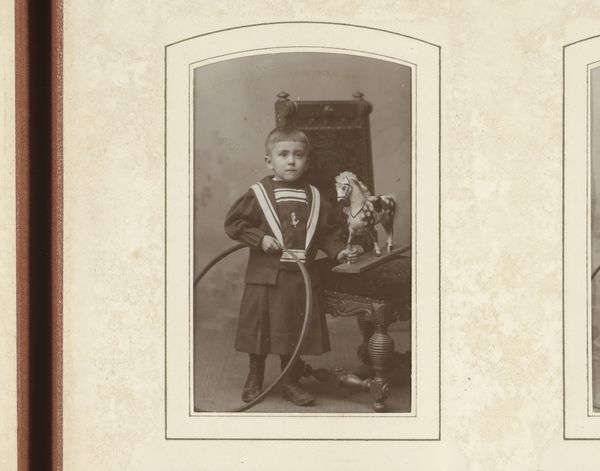

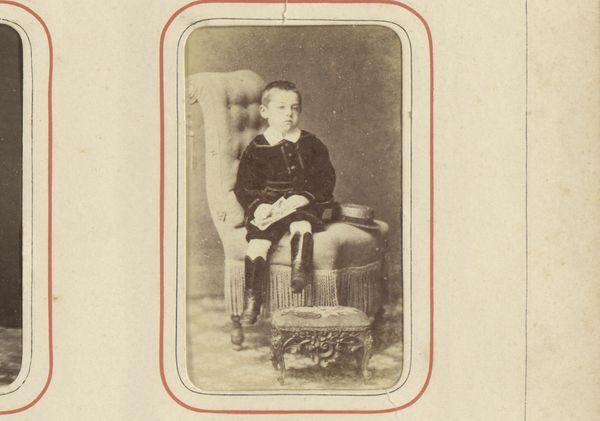

Curator: This is a fascinating example of late 19th-century photography from the studio of Brainich & Leusink. It's titled "Portret van een jongen met hoepel in de hand", which translates to "Portrait of a boy with hoop in hand", and likely dates between 1881 and 1904. Editor: It’s instantly melancholic, isn’t it? Despite the presence of what appears to be a toy, the child's posture is rather stiff and his expression quite serious. The muted tones of the photograph contribute to this solemn mood. Curator: Yes, the serious formality was typical for portraits of that era. Photography was still somewhat novel, a rather precious and posed undertaking, not the ubiquitous snapshot we know today. The hoop was likely included as a symbolic element suggesting youth and activity. However, his rather theatrical outfit reads more like a costume than everyday clothes, signaling aspiration rather than personal representation. Editor: Exactly! And the carefully staged setting suggests more about societal expectations of childhood and family presentation than perhaps about this particular boy. His isolation in the frame—that severe oval border—amplifies the feeling of restraint. You said hoop... I initially read the shape and colour as some pale halo behind his head. Curator: That's an insightful observation. Consider that symbols evolve—or perhaps devolve, losing some resonance over time, but their ghost of significance remains. Perhaps to the parents who commissioned this image, the hoop suggested innocence and promise, things devoutly wished for in their family, projected on their offspring in photographic form. For later viewers, it's tinged with a little loss. Editor: Perhaps the severity of the boy’s dress has been lost on me up till now as well: this feels so strongly of the bourgeois values of its time: self-discipline and earnestness are more on display here than freedom of spirit. Is that a harsh reading? Curator: I believe it’s an accurate one, supported by a broader analysis of the period and its artistic conventions. What this work triggers most strongly is that photographs carry meaning precisely through what they attempt to suppress—that tension can be especially potent and visible to contemporary eyes, used to images in overabundance. Editor: Thinking about all this...it encourages me to approach similar portraits with renewed consideration for not just who's in them but who is absent, institutionally or systematically, how we inherit ways of seeing from the past. Curator: Agreed, and how looking at those historical patterns helps understand our present assumptions as well.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.