drawing, paper, pencil

#

portrait

#

pencil drawn

#

drawing

#

light pencil work

#

baroque

#

pencil sketch

#

paper

#

portrait reference

#

pencil drawing

#

pencil

#

portrait drawing

#

italian-renaissance

#

portrait art

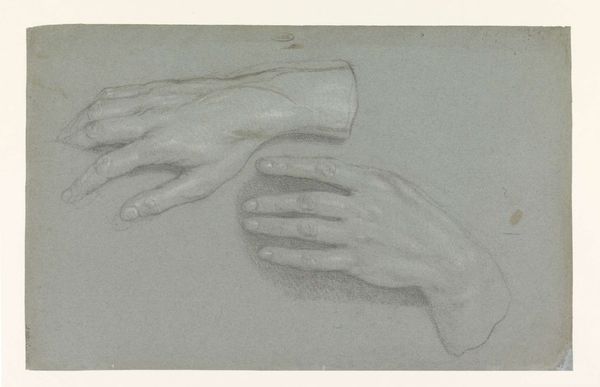

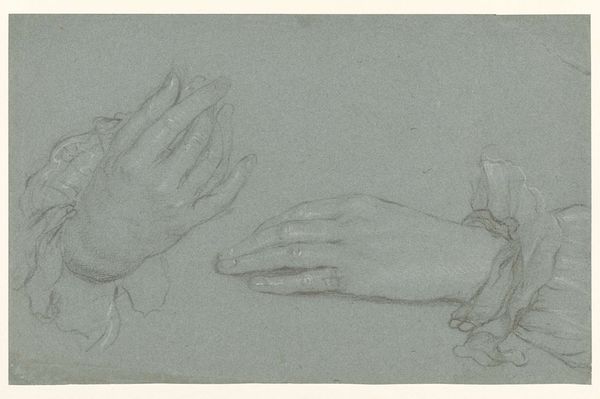

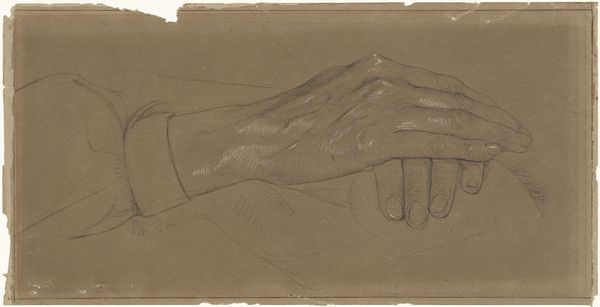

Dimensions: height 277 mm, width 418 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: I'm struck by the gentleness of this work, it feels incredibly intimate. Almost like a whisper. Editor: Indeed. We’re looking at “Two Women’s Hands, One with a Handkerchief,” a pencil drawing by Anthony van Dyck, created sometime between 1610 and 1641, here at the Rijksmuseum. It's a simple study, really, just hands, rendered in delicate detail on paper. Curator: "Simple" perhaps belies its power, though. Van Dyck captures so much with so little. There's an almost tangible tenderness. I find myself wondering about the women. Are they comforting each other? Saying goodbye? There’s a sense of shared sorrow, maybe, in that small piece of fabric. Editor: That’s interesting. For me, that handkerchief points towards societal expectations. Women in this era were so heavily defined by their domestic roles, the control of emotions. This could be a subtle commentary on those restrictions and also the hidden labour of care that women performed. The handkerchief almost acts as a signifier. Curator: You see confinement; I initially saw comfort. It’s funny, isn't it? Art refracting back our own experiences. Perhaps it is both. The constraints you speak of *and* the small rebellions of intimacy within them. The drawing’s almost monochrome quality amplifies the subtle details – the lines in their palms, the gentle curve of their fingers. It highlights how deeply human, and how quietly radical, such moments of shared touch could be. Editor: I agree, and to bring it to our current moment: How can we connect it to discussions of care and visibility, and who is afforded the time to draw in a period like this? What economic means were necessary? Curator: Those are the truly difficult questions. And the reason we keep engaging with art centuries later, yes? Finding threads connecting then and now...recognising both the timelessness of human emotion and the persistent echoes of societal structures in art, hopefully pushing forward, one tiny reflection at a time. Editor: Precisely. Each viewing is an opportunity to unpick and reassemble meaning.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.