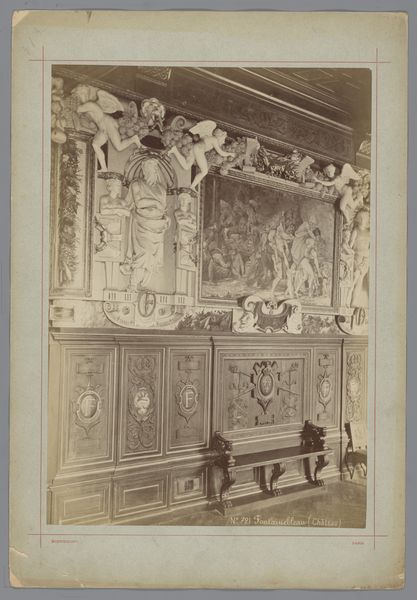

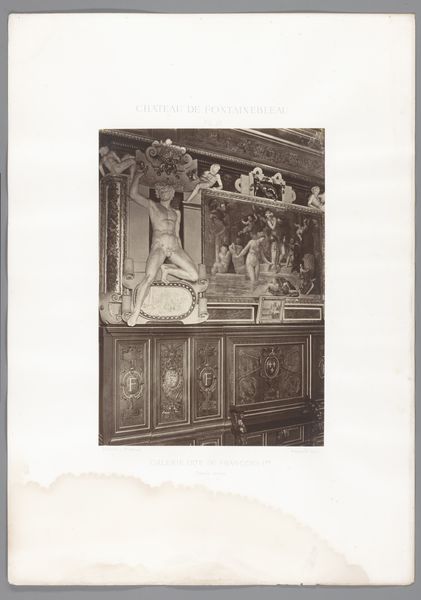

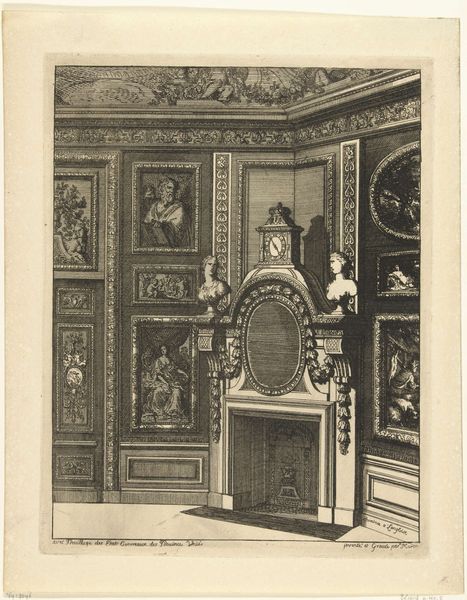

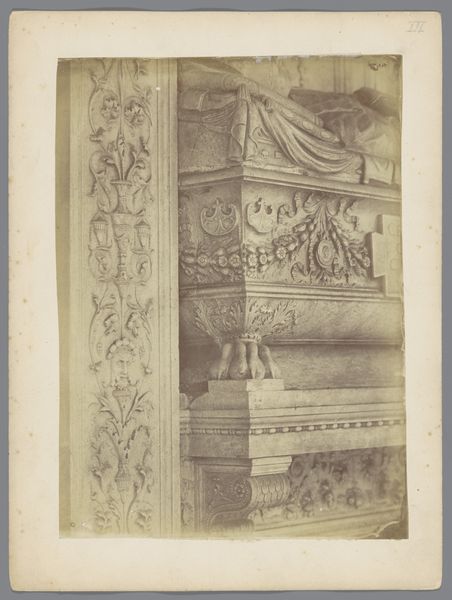

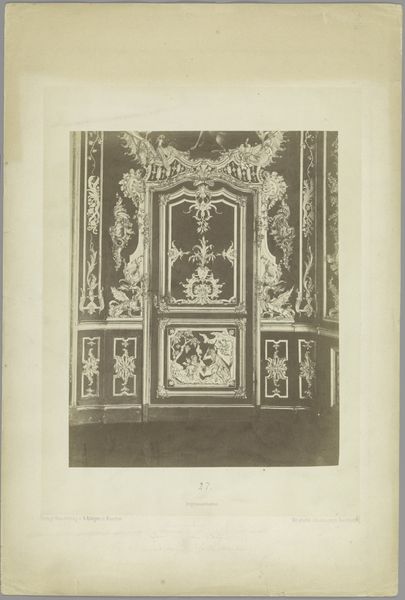

Deel van de galerij van François I in het paleis van Fontainebleau c. 1875 - 1900

0:00

0:00

medericmieusement

Rijksmuseum

Dimensions: height 354 mm, width 250 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Looking at this print, made sometime between 1875 and 1900, the details jump out immediately, it's a photo taken by Médéric Mieusement called “Part of the Gallery of François I in the Palace of Fontainebleau." Editor: The grandeur is instantly apparent! Even in this monochromatic photograph, the ornateness overwhelms the eye—the eye immediately drifts upward as a kind of classical aspiration, though its material roots also appear... weighty, immutable. Curator: Observe the composition. Note the rhythmic interplay of forms—the curves of the sculpted figures against the strict geometry of the paneling, all carefully positioned to create a visually arresting experience. This is Neoclassicism distilled. Editor: Yes, and if we dig into how the room would have been built in the first place, with the material choices and the skilled labor involved, there's this tension with the almost sterile refinement that the print aims to capture... think about the different textures in each element: The rough hewn nature of a marble statue against a print depicting a painting is significant. Curator: Absolutely, though the texture speaks volumes within its own language—it reveals the status of the room’s commissioner as an act of class and state propaganda and the history-painting showcased is deliberate, crafting and reinforcing historical narratives, legitimizing power. The interplay isn’t just aesthetic. Editor: The status is absolutely constructed, I see this as rooted deeply in the consumption, both visual and economic, don't you agree? Consider who owned the gallery versus those who contributed physical labor to erecting such architectural work. Curator: Undeniably. But Mieusement also aestheticizes power; the formal qualities serve this very potent social and political role by crafting visual grandeur through line and composition in and of itself. Editor: Which gets tricky given photography’s own evolving means of production… who is this photograph for, what material conditions made the printing of photographs for the masses even possible in the first place? Food for thought. Curator: Precisely. I depart having further clarified my ideas through dialogue; hopefully, the artwork itself yields these complexities further to our audience. Editor: And for me, it underscores the tangible effort of art creation and consumption within evolving networks of production! Thanks to this particular captured viewpoint and critical conversation!

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.