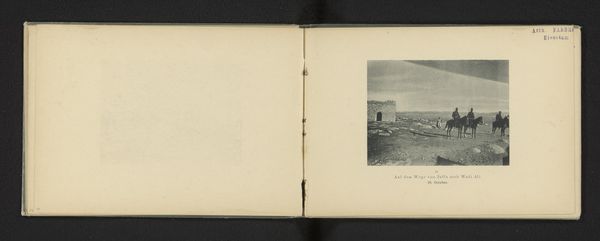

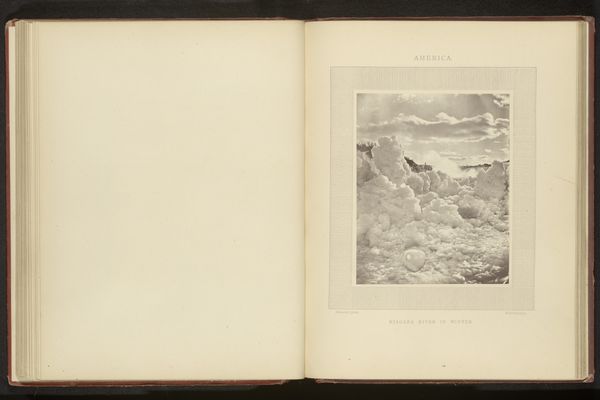

photography, gelatin-silver-print

#

landscape

#

photography

#

orientalism

#

gelatin-silver-print

#

realism

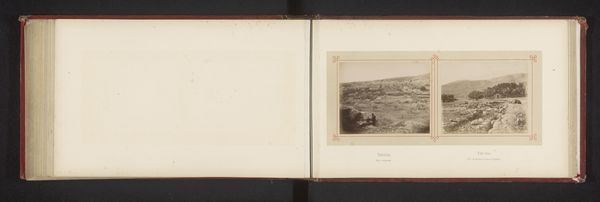

Dimensions: height 76 mm, width 102 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: We're looking at a gelatin-silver print titled "Joppa. View from the West," taken by Francis Bedford before 1865. It captures a distant view of the ancient port city. Editor: It’s immediately striking—almost unsettling. The contrast is quite stark, casting a severe, isolating light. The textural details are sharp in the foreground, softening considerably in the distance as it disappears into that bleached horizon. Curator: Absolutely. Bedford was one of several photographers working in the mid-19th century who traveled to the Near East, then considered the Orient, documenting landscapes and sites of Biblical significance for a European audience hungry for visual representations of these places. Photography like this helped shape Western perceptions of the region. Editor: What I find fascinating is how he's framed the scene. Notice how the relatively empty foreground gives way to that tightly packed town. It directs the viewer's eye in a very controlled manner, from emptiness towards what the photograph asks us to perceive as civilised density. It emphasises the composition in such a calculated, linear fashion, almost geometric. Curator: Precisely. And Bedford wasn’t just passively recording. Consider that photographers operating at the time were burdened with cumbersome equipment and slow processes. Creating images required extensive preparation and technical skill. Each frame presented an opportunity to not only document a location but also to subtly endorse the imperial gaze of the European powers. It's important to consider what the exclusion and inclusion of details convey in itself. Editor: Very true. Thinking about his darkroom process as an artistic gesture...I see how each shift in tonal values carries deliberate visual meaning, emphasizing certain details for emphasis. You almost begin to see an act of symbolic transcription. Curator: Indeed. And with an artistic strategy built around documentation for public consumption, these seemingly objective photographs became important cultural and political tools in Britain during an age of Imperialist aspirations. Editor: It brings to mind the power of an image, doesn't it? How lines and tones, light and shadow, speak not just to what we see but to what we’re made to believe. Curator: It invites us to really interrogate images of places distant in space or time: Who produced it? Why? For whom? That's key here.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.