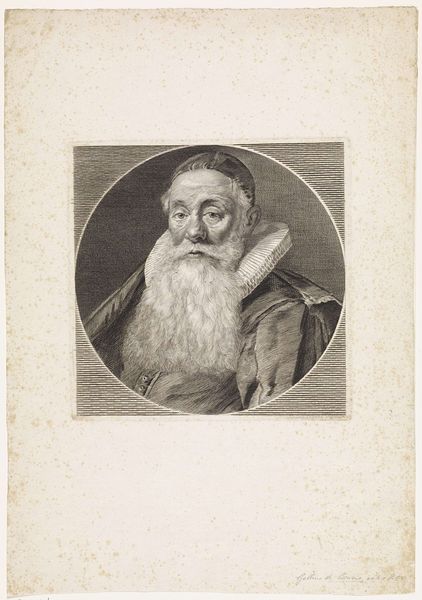

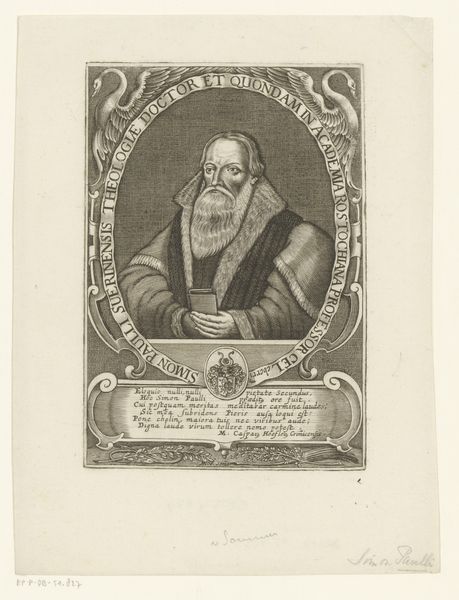

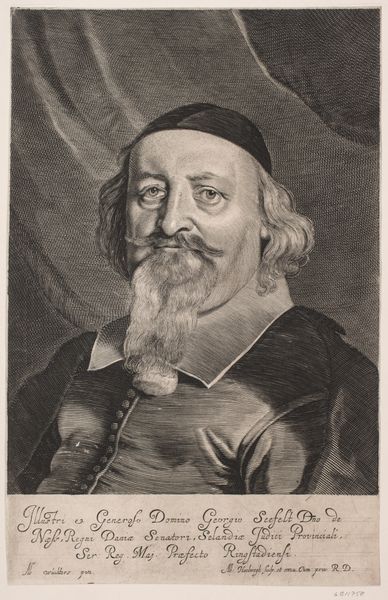

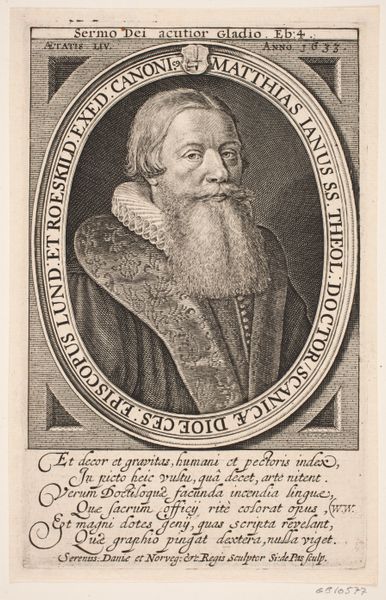

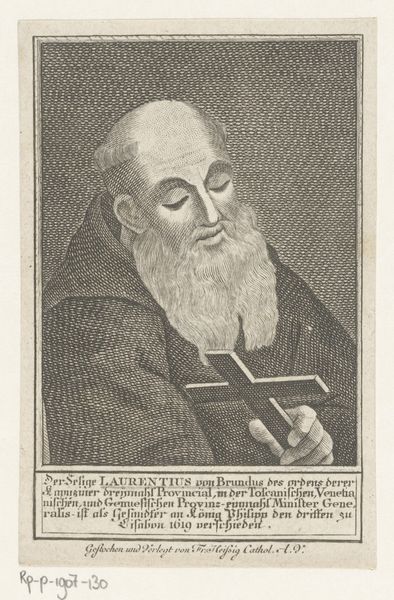

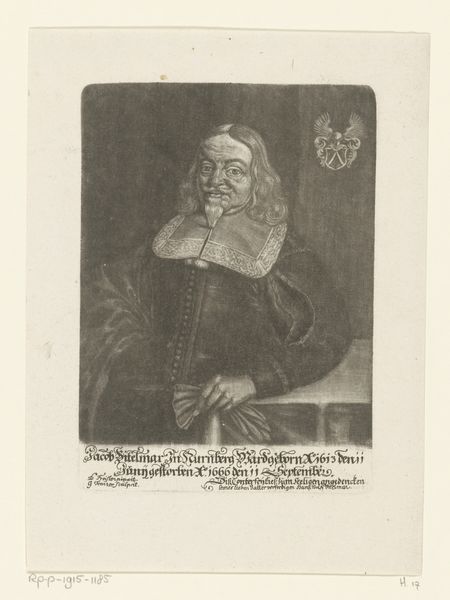

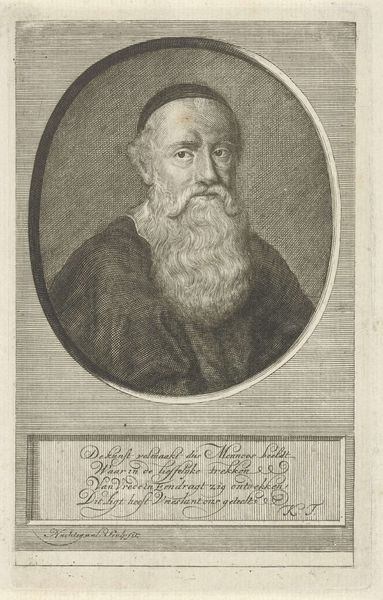

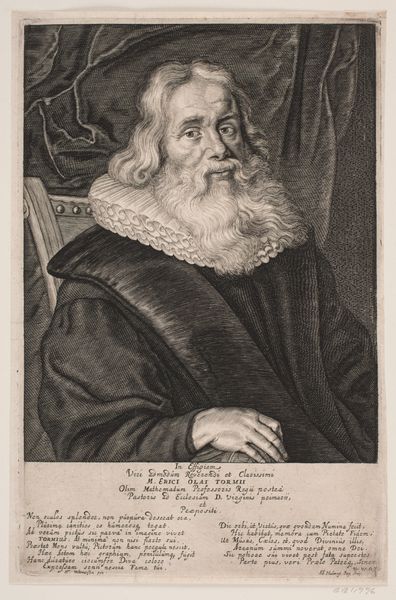

print, engraving

#

portrait

#

baroque

# print

#

portrait reference

#

portrait drawing

#

history-painting

#

academic-art

#

engraving

#

realism

Dimensions: 230 mm (height) x 155 mm (width) (plademaal)

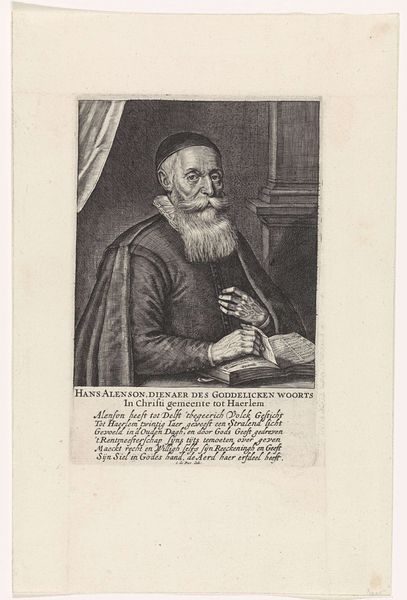

Curator: What strikes me immediately about this print is its palpable gravity. The sitter’s age is etched into every line. Editor: Indeed. We're looking at a portrait of Gabriel Kyng, rendered in engraving by Albert Haelwegh during the 1660s. It resides here at the Statens Museum for Kunst. What are your thoughts on this piece? Curator: The detail is quite impressive, especially the way Haelwegh captured the texture of Kyng’s beard and the slight sag of his eyelids. It really brings a sense of his presence across the centuries. But I can't help wonder how accessible this kind of portrait would have been. Who exactly was it made *for*? Editor: Good question! This work is fascinating for how it merges the visual language of power with an air of religious piety. Notice the book at his side. The portrait text beneath makes grand pronouncements that translate as, “Here, reader, you have the face of Gabriel...”. Consider the very act of disseminating the sitter's image so widely—a political and social strategy used to broadcast and cement influence at the time. Curator: Exactly, and the trappings reinforce this. He wears what appears to be clerical attire, yet the overall feel isn’t overly austere. There is almost a theatrical staging with the curtain, isn’t there? The whole composition frames Kyng within a specific historical narrative. It's a masterclass in crafting a public image. Editor: That staging gives me pause, though. There is a distinct class element in play. Consider that only elites get their portraiture permanently affixed onto metal. This fact situates Kyng inside specific, exclusionary networks of power at the time. I am also curious as to whether he had any say regarding how he would be represented or distributed! Curator: I take your point entirely! Despite any supposed democratization afforded by printmaking at the time, images still operate within social hierarchies. That intersection between artistic representation and social structures is incredibly rich. Editor: Indeed. Haelwegh’s engraving achieves a striking balance between capturing individual likeness and upholding social standing in early modern Europe. Curator: Ultimately, this artwork reveals the degree to which our own perspectives inform interpretations, influenced by evolving knowledge of art history and critical studies!

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.