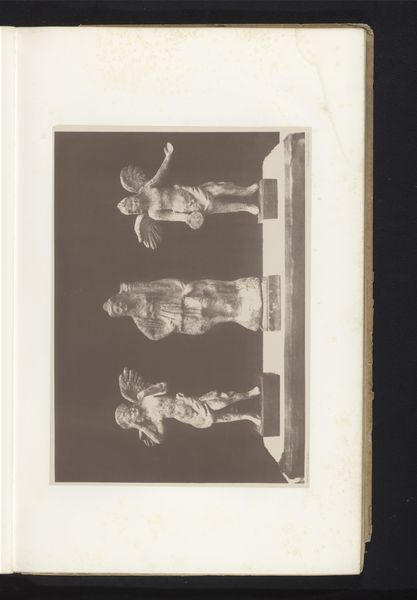

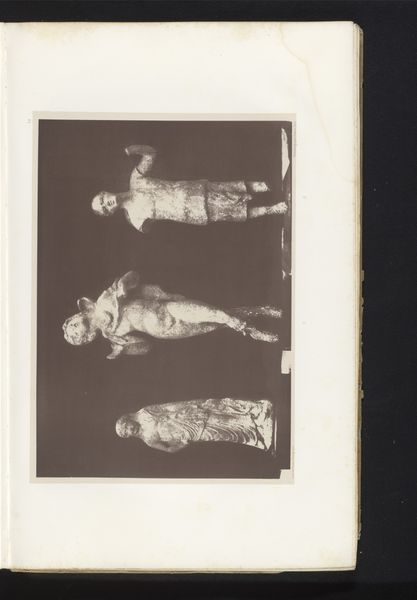

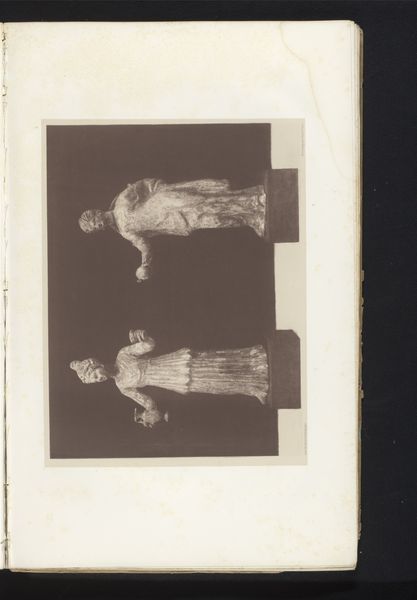

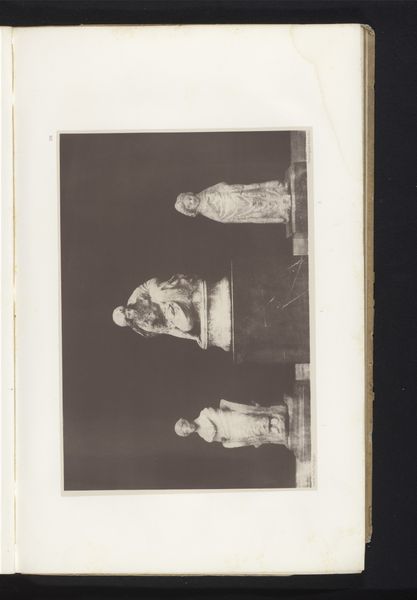

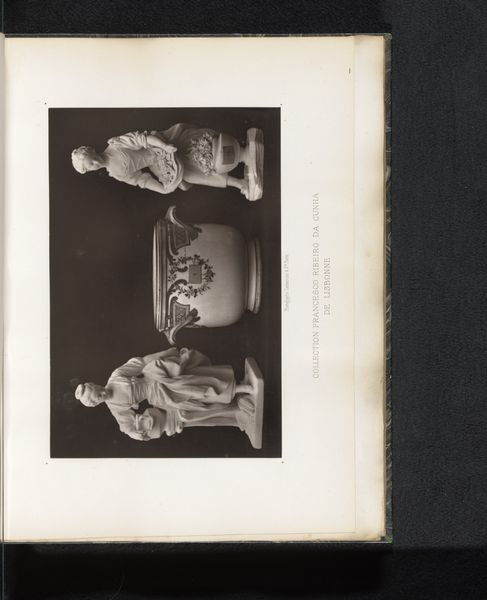

Drie terracotta sculpturen van een zittende Diana, een slapend kind in een wieg en Thetis before 1857

0:00

0:00

print, ceramic, photography, sculpture

#

portrait

# print

#

sculpture

#

greek-and-roman-art

#

ceramic

#

figuration

#

photography

#

sculpture

#

ceramic

Dimensions: height 239 mm, width 361 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

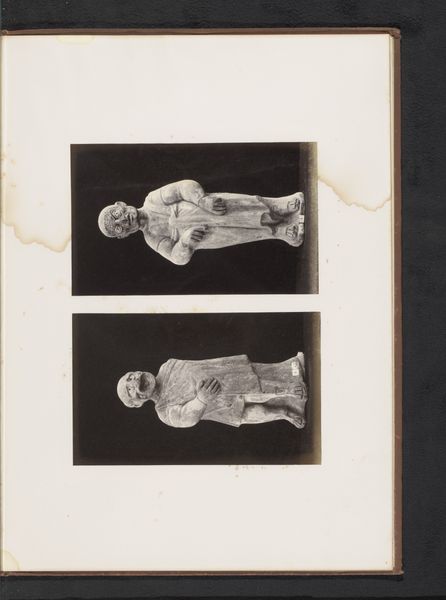

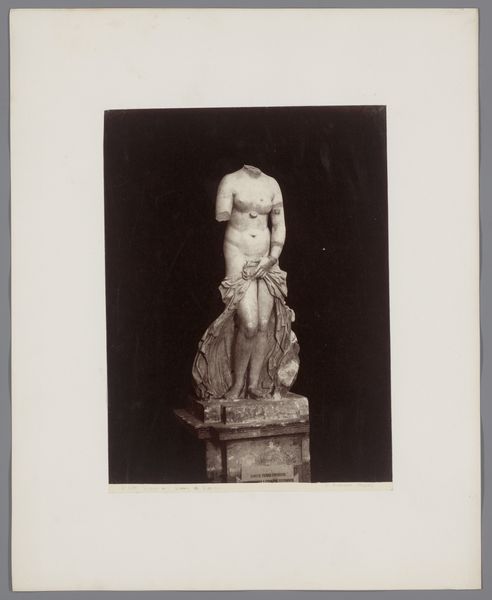

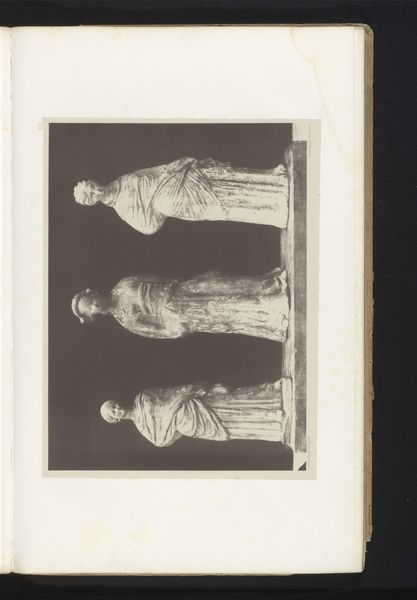

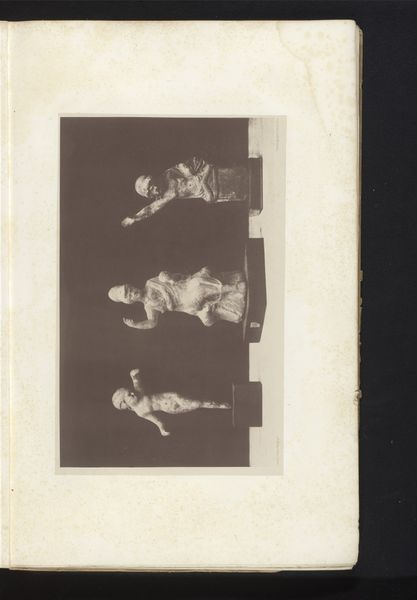

Curator: Here we have a photograph taken before 1857, attributed to Marcel Gustave Laverdet, depicting three terracotta sculptures. The works showcase a seated Diana, a sleeping child in a cradle, and Thetis. Editor: Well, my first thought is that the photo captures a kind of ghostly domesticity. These aren’t grand, monumental sculptures, but intimate scenes. I can almost feel the clay beneath my fingers; the unglazed surfaces giving a tactile impression, contrasting with the crispness of the photographic print. Curator: Exactly. Laverdet was documenting artworks, a practice situated within the burgeoning field of art history and the rise of museums. Photography was critical in disseminating knowledge, making these pieces available for study beyond their physical location. The print allows, or even encourages, comparison across geographies, for scholars to consider stylistic commonalities in relative isolation from their objecthood. Editor: Which is interesting because the means of reproduction—the photographic print itself—distorts our perception of the object, stripping it from any haptic sensory of material. But the fact they're presented together draws my attention to the way the sculptor must have handled and formed the clay, probably quite quickly to capture the intimate subject of the child asleep. There's a visible mark making of labour there. The image hints to a complex, delicate manipulation. Curator: Absolutely, and this gets to the heart of how classical themes were being reinterpreted. The sleeping child in a cradle, for instance, introduces a new form, that invites a connection between domestic intimacy and these established Greco-Roman motifs. Think about the societal shifts happening then—the focus on domesticity, sentimentality and new ideals of femininity. Editor: The reproduction might undermine their artistic integrity as pieces, which could be further exacerbated by them being ceramic: such a readily available and cheap resource by this point, especially since classical and renaissance artists typically worked in marble for their sculpture. How did using ceramic in the classical tradition allow a new audience access to the artform and narrative? Curator: An astute point, these works could also question who could produce artworks like this, maybe even democratising creation; where fine arts begin and domestic arts end become harder to clarify, particularly if Laverdet presents them without comment or critique, but as document. Editor: Considering them this way has definitely changed my first impressions, focusing more on how they reflect historical power relations and shifts through materiality and artistic labor. Curator: Mine too! Placing this photograph in the context of visual culture of the time makes us consider how these sculptures are part of broader conversations on classicism, gender, and social identity.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.