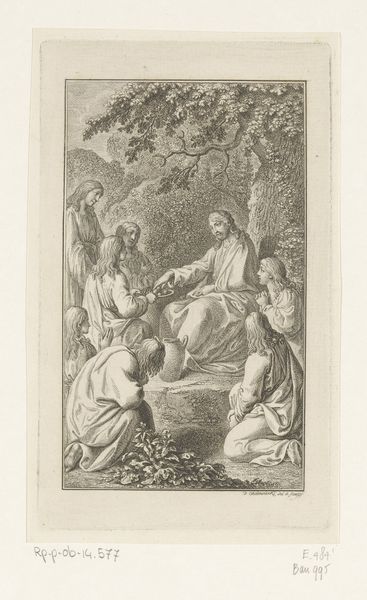

Dimensions: height 126 mm, width 72 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Welcome. We're looking at Daniel Nikolaus Chodowiecki’s “Bergrede van Christus” from 1776, currently held in the Rijksmuseum. It’s an engraving. Editor: My first impression is how intimate it feels. Despite the historical distance, Chodowiecki manages to capture a very human, relatable scene. Curator: Indeed. Chodowiecki excelled at translating biblical narratives into scenes reflecting the sensibilities of his time. Look at the line work: intricate, precise, almost photographic in its detail despite being a line engraving. Editor: It’s interesting to view this through a socio-political lens. The Sermon on the Mount itself—a foundational text for many liberation movements—is staged here in a way that domesticates its radical potential. Curator: I can see that. The setting, under a large tree, suggests not just a casual atmosphere, but echoes traditional images of wisdom and gathering. It’s also interesting that the tree almost protects those who sit around, reinforcing feelings of community. The figures themselves carry familiar symbolic weight—consider how each member around Christ gazes up towards him with various looks, whether awestruck, contemplative, or even bored. The faces reveal the whole of humanity that looks toward religion with many hopes and doubts. Editor: And how are women represented here? Seated somewhat separately, near the children. Is it an unintentional artifact of the time, or is Chodowiecki consciously engaging with ideas around women's roles in spiritual learning? This calls to mind a history of limited access and quiet, segregated worship. Curator: That’s a crucial question. In terms of the children—I notice some playing, others simply present—Chodowiecki visualizes something often described: that Christ appealed to all types of people, not just mature scholars and priests. These visual symbols, then, resonate with cultural and theological memories. Editor: So, while we may interpret Chodowiecki's piece through the prism of contemporary power dynamics and identity politics, we shouldn’t negate how it was initially understood. Curator: Exactly. Understanding art like this involves balancing cultural legacies and new readings—not cancelling anything. It requires seeing and acknowledging pasts without negating present injustices. Editor: A continuous project of bridging dialogues between what once was, what is, and what could be.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.