tempera, photography, albumen-print

#

tempera

#

landscape

#

photography

#

ancient-mediterranean

#

orientalism

#

19th century

#

albumen-print

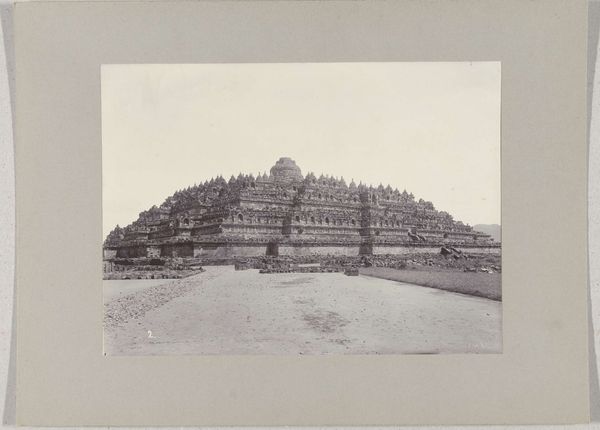

Dimensions: height 195 mm, width 247 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

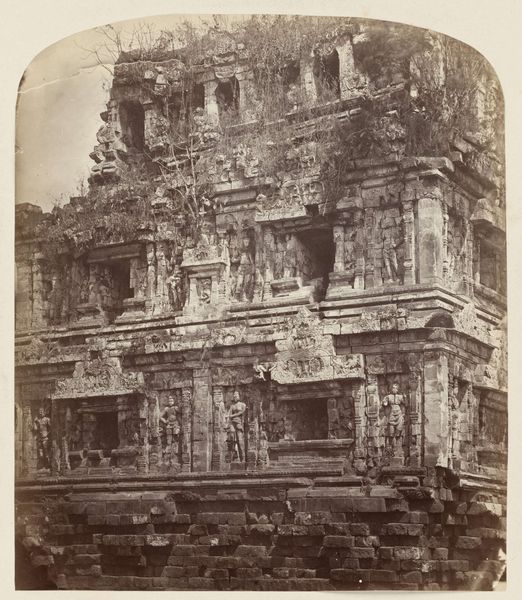

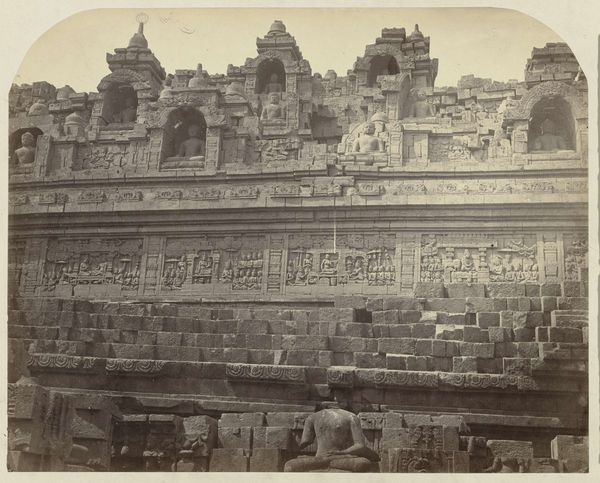

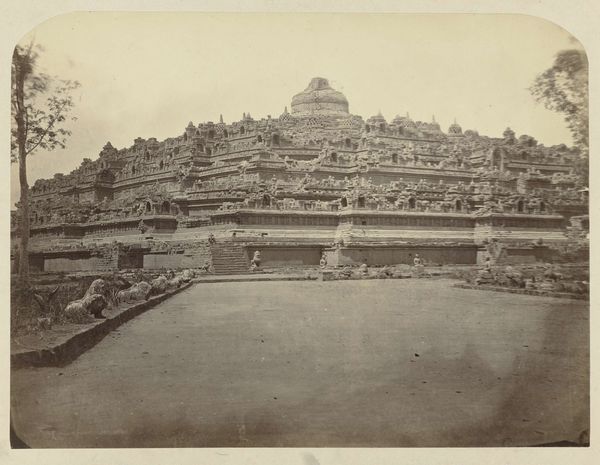

Curator: This albumen print, captured by Woodbury & Page, shows the Borobudur in Java, dating roughly from 1857 to 1870. What are your initial thoughts? Editor: Monumental. There's an overwhelming sense of weight, not just the literal mass of the structure, but a historical gravitas, amplified by the monochromatic tones. Curator: Indeed. And that weight is interwoven with the complex history of colonialism and orientalism. Woodbury & Page, as European photographers, played a role in constructing a Western gaze upon Southeast Asia, presenting it through a specific lens for European consumption. Editor: You can see the conscious framing—the almost reverential angle accentuates the Borobudur's symbolic power, like a pyramid climbing toward enlightenment. It recalls countless other visual representations of sacred spaces. Are we meant to see a timeless, spiritual essence here, or a relic viewed through the colonial mindset of the photographers? Curator: I think it's both, inextricably linked. The architecture itself represents a layering of cultural and religious influences, primarily Buddhist. But this photograph enters that narrative as a document shaped by imperial desires and ethnographic curiosity. We must acknowledge the photographer's power to curate and control the image’s narrative. How do choices related to camera height, composition, the time of day can convey certain ideologies, consciously or not? Editor: The detail within the temple hints at so much untold narratives. If we analyze each frieze or sculpted element in this photograph, what specific myths and allegories might be found? I want to decode the symbols. What visual cues were intentionally left, repeated and hidden in plain sight? What stories did Woodbury & Page choose *not* to tell? Curator: That’s key – the silences, the absences within the photographic frame. Consider what this image was *for* – its audience, its original purpose as part of a broader project of cataloging and classifying colonized spaces. These details remind us of the politics inherent to documentation itself. Editor: Yes, ultimately the image pulls us in. It invites this dialogue and leaves space for interpretation beyond a purely visual impact, that explores an echo chamber of cross cultural encounters and power relations. Curator: Exactly. A visual document that encourages us to analyze and to interpret across both temporal and cultural realms.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.