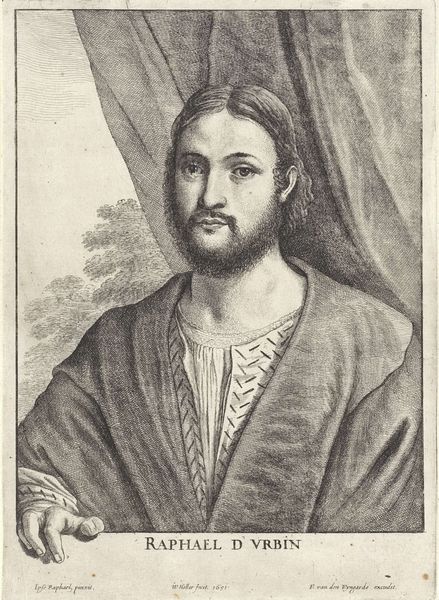

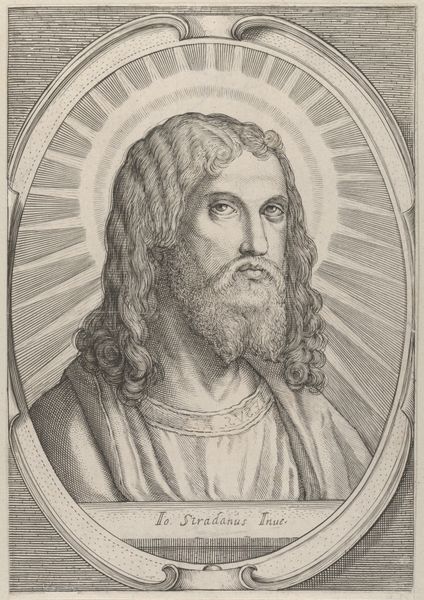

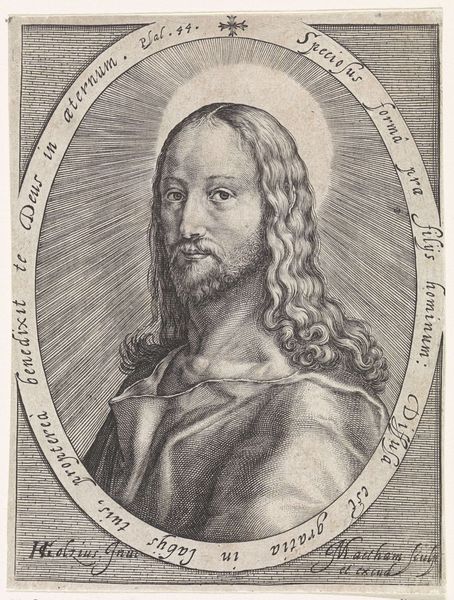

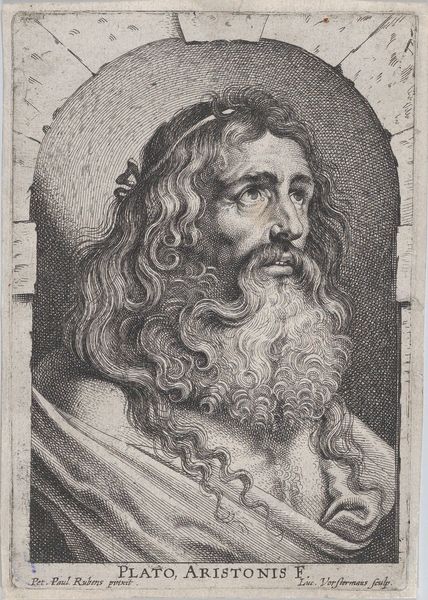

print, engraving

#

portrait

# print

#

old engraving style

#

mannerism

#

figuration

#

line

#

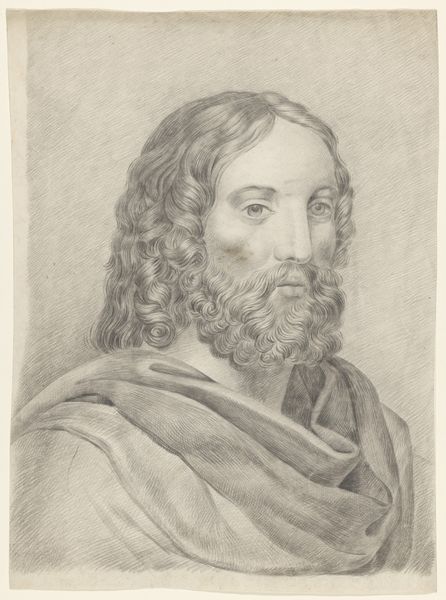

portrait drawing

#

history-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 280 mm, width 186 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: This is Giulio Bonasone's "Portret van de kunstenaar Rafaël," a print dating somewhere between 1501 and 1580, currently housed in the Rijksmuseum. My first reaction is how detailed the linework is; there’s such intricacy etched into the plate. What do you see? Editor: I feel a gentle melancholia looking at it. He seems like someone caught between worlds. Maybe it’s just the way the light and shadow play across his face. Curator: That melancholia resonates. This piece exists within a complex social and art-historical context. Bonasone, as a printmaker, was functioning in a reproductive industry. He wasn't creating an original image in the same vein as a painter. The engraving technique itself—the meticulous carving into the copperplate— speaks to a craftsman's labor. Editor: It's interesting that you focus on labor, because all that I see is line. Every hair, every shadow—they're all created with line, and not a single line feels accidental. What does this repetitive, committed labour communicate? Maybe there's beauty in all the making itself. Curator: It certainly raises questions about artistic intention. Bonasone’s intention was, most likely, to disseminate an image, to make Raphael accessible to a wider audience who couldn’t afford an original painting. The very act of reproduction shifts the artwork's status; its value changes depending on who owns it. Editor: That's very matter-of-fact; is there not something sacred about it? Here's Raphael, captured in a single moment. The texture almost reminds me of woodcuts or early printed books, as though he existed to inhabit these reproducible, useful forms. His genius becoming democratic through dissemination. I also feel it echoes the artist as almost saint-like in cultural importance, a figure of divine inspiration. Curator: An interesting point, if perhaps overly romantic! I'm interested, however, that these reproductive techniques blurred the lines between artistic creation, craftsmanship, and commercial enterprise. Editor: Ultimately, I agree. The image reflects both skill and industry; there's an intersection of technical production, artistry, and emotional representation here that makes me see him in a way painting never could. Curator: A fitting thought with which to end, I think, reminding us how historical artistic outputs never speak just one message or tell only one story.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.