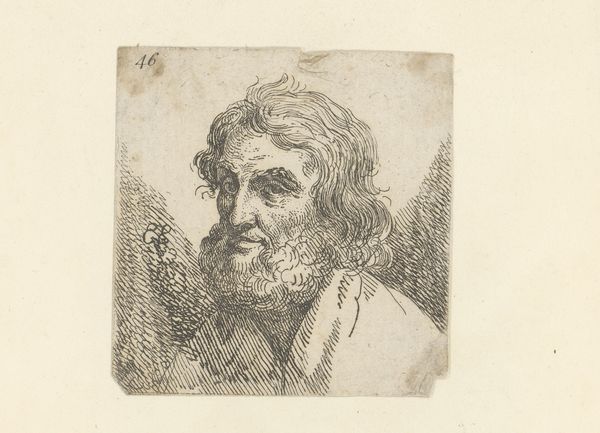

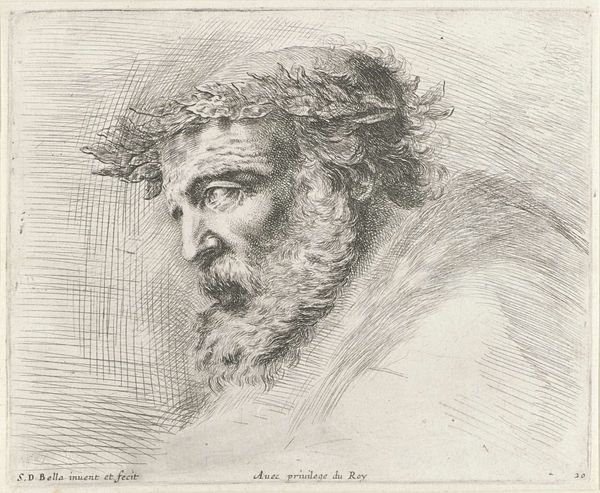

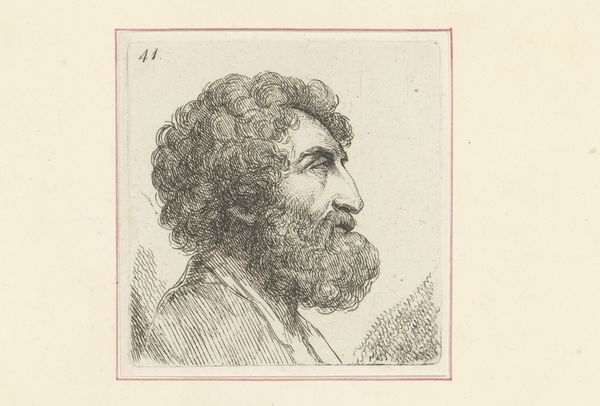

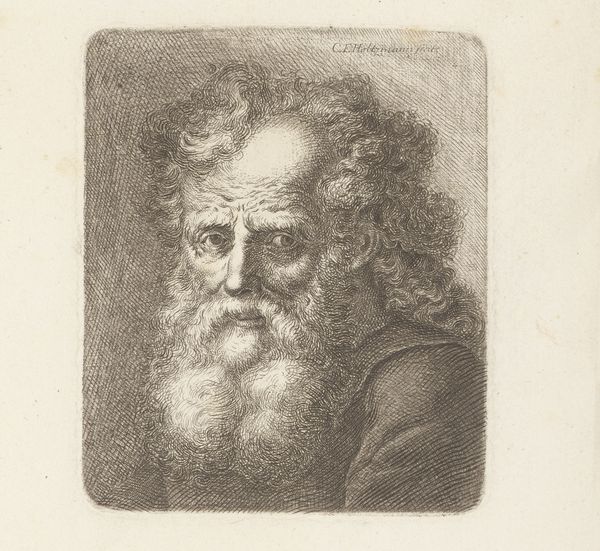

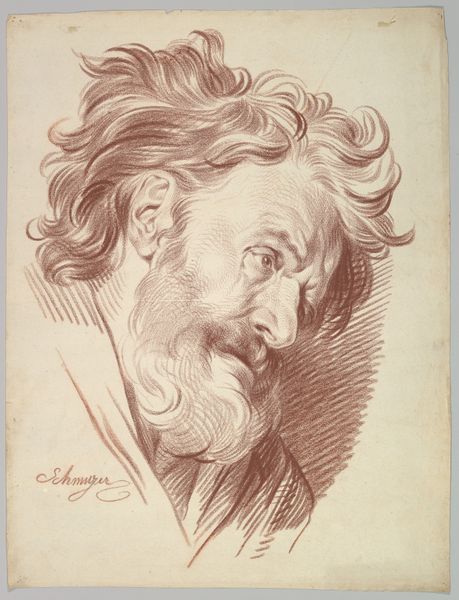

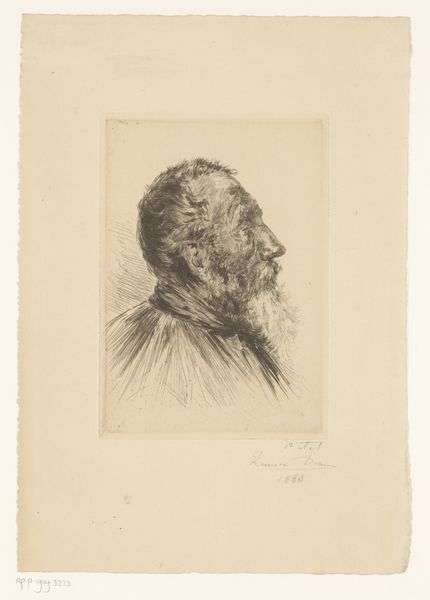

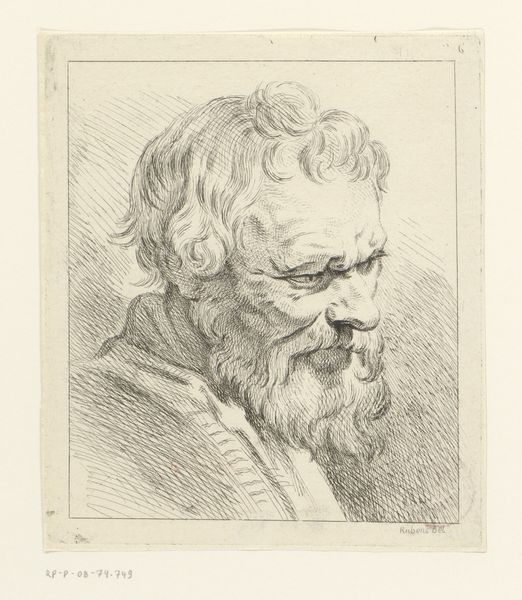

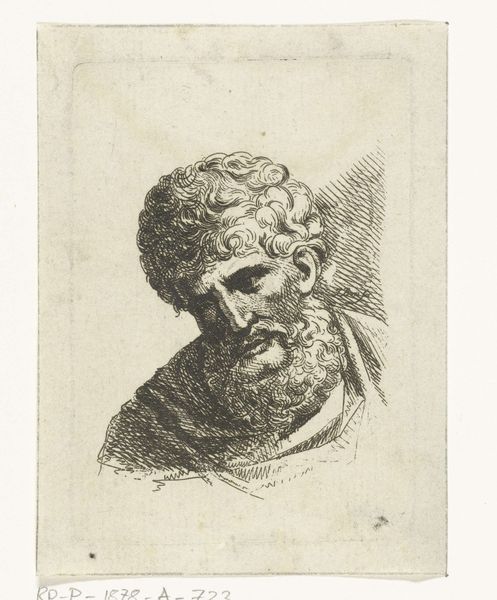

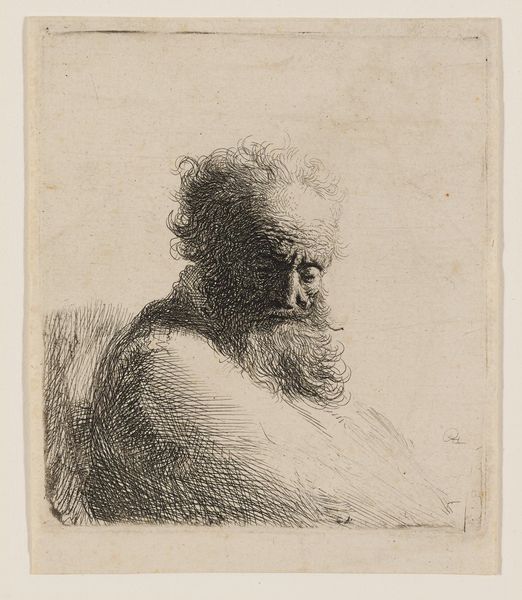

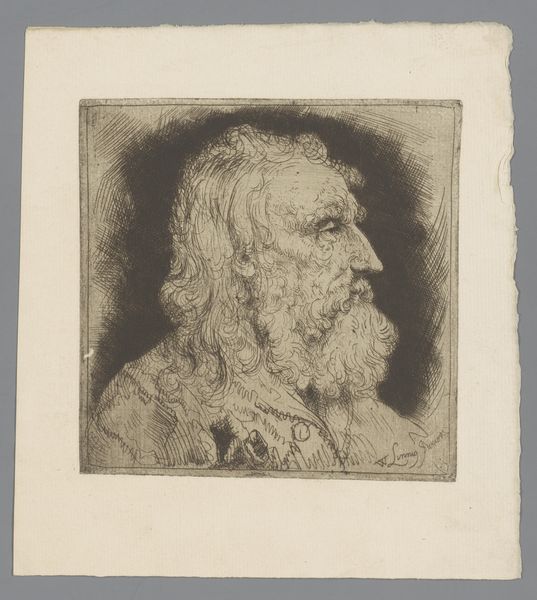

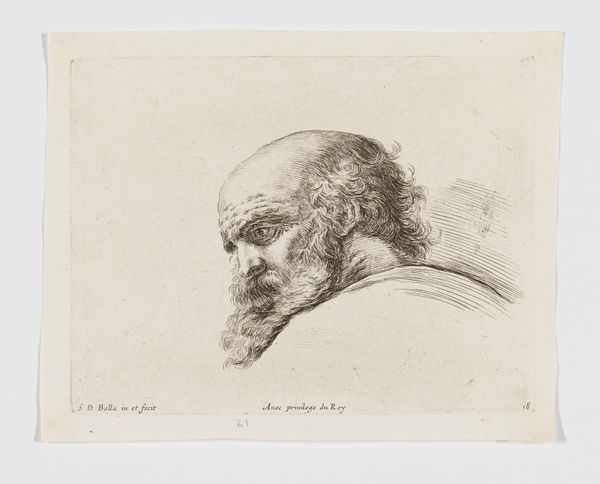

drawing, print, etching, engraving

#

portrait

#

drawing

#

baroque

# print

#

etching

#

engraving

Dimensions: 4 11/16 × 5 3/4 in. (11.91 × 14.61 cm) (plate)5 7/16 × 6 1/2 in. (13.81 × 16.51 cm) (sheet)

Copyright: Public Domain

Editor: Here we have Stefano della Bella's "Head of a bearded old man" from around 1641, created using etching and engraving. The intricate line work really captures the man's aged features. What's your interpretation of this portrait, considering the socio-political context? Curator: It’s important to consider the Baroque era, and della Bella’s position within court culture. He worked for the Medici family, known patrons of the arts who utilized artwork for propaganda and self-fashioning. Is this then a truthful study of old age, or perhaps an idealization, aligning with ideas about wisdom and authority, circulated through imagery? Editor: That’s fascinating. I hadn’t thought about it as potentially strategic image-making. So, even in what seems like a simple portrait, there’s a layer of political intention? Curator: Potentially, yes. Etchings like these circulated widely, influencing perceptions beyond the immediate court. Also, note the laurel wreath. In what contexts would that symbol be familiar to viewers? It is a signal, and part of the visual vocabulary of power and status. The distribution of these prints played a part in constructing ideas about leadership. Editor: So, the choice to depict the man with the wreath is deliberately alluding to something beyond just a man. What did that signify at that time? Curator: The laurel wreath was a symbol linked to ancient Rome, to emperors and military victors, thus royalty. Its appearance in portraits associates the sitter with those historical ideals of power, which in turn elevates his stature and the family that might commission such works. We have to think of the cultural framework informing viewers at that time. How would this image be *read* by its intended audience? Editor: I see now. The portrait then functions almost as a kind of branding. Thanks, this really broadened my understanding. Curator: Indeed. Examining art within its historical, social, and political environments can reveal fascinating aspects we might otherwise miss.

Comments

minneapolisinstituteofart about 2 years ago

⋮

The accomplished Florentine etcher and draftsman Stefano della Bella produced this drawing manual in France, where he spent over a decade of his career. The book, now disassembled, comprised 25 etchings and was published by della Bella’s principal French publisher Pierre Mariette. Drawing manuals were common teaching tools for artists and amateurs learning to draw in the 16th and 17th centuries. It is a kind of pattern book for the aspiring draftsmen to copy, with concise prints depicting body parts—ears, eyes, hands, feet—and a range of head studies and figure types—children, adolescents, young women, old soldiers and saints—which provide models for students seeking to master the representation of the human body.

Join the conversation

Join millions of artists and users on Artera today and experience the ultimate creative platform.