print, engraving

#

portrait

# print

#

old engraving style

#

sketch book

#

figuration

#

11_renaissance

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 167 mm, width 125 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

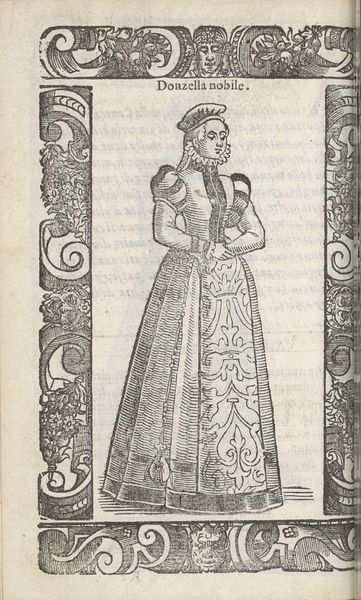

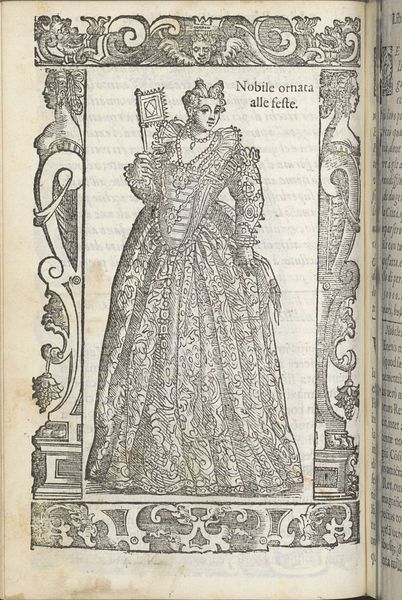

Curator: This engraving, titled "Vergine Patritia", was created around 1598 by Christoph Krieger. The lines feel quite precise, and the figure projects an air of self-assuredness. Editor: It's visually quite striking. The subject emanates an almost austere dignity. I find the ornamental border equally captivating; those cherubic faces contrast quite strongly with the serious countenance of the noblewoman. Curator: Indeed. Let’s consider the context: Engravings like these often circulated as part of printed books, readily disseminating information about fashionable dress and ideals of social status across geographical divides. Editor: Absolutely, and that clothing speaks volumes. Every fold, every carefully placed line denoting fabric and ornament reflects the intricate rules governing social performance in the late Renaissance. We can analyze her dress, her posture, and the symbolic elements incorporated in the garment's design to uncover messages about family, lineage, and virtue. Curator: Yes, the very act of engraving is a meticulous, laborious process. The print medium democratized image production and distribution to a degree, compared to unique painted portraiture. Each impression bears witness to the engraver's skill, but also, potentially, to the labor dynamics of printmaking workshops. Editor: But Krieger's conscious choices regarding symbol placement—consider that ornament at the center of her bodice—was designed to reinforce this woman's social standing. Note how she holds the chain to the front of her skirts... a deliberate presentation. What would her contemporaries have interpreted? The faces in the ornamental borders: Do they speak to divine witness of her nobility or familial symbols meant to reflect ancestral virtue? Curator: Perhaps both? I think by focusing on Krieger's technique, and how engravings themselves facilitated new dialogues about art, manufacture, and consumption in Early Modern Europe, we can illuminate previously unacknowledged histories embedded in its materiality. Editor: That's insightful. Thinking of these symbols not as isolated aesthetic features but as communicative devices reflecting layers of social meaning helps unlock that understanding you mention. We’ve opened a new doorway for listeners now! Curator: Precisely. It shifts our understanding from a focus merely on beauty and enters the domain of social utility. Editor: Agreed. It goes far beyond an artistic portrait, providing insights into class and gender. I encourage visitors to delve deeper into the meaning behind the dress, jewelry, and ornamental elements in this captivating image.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.