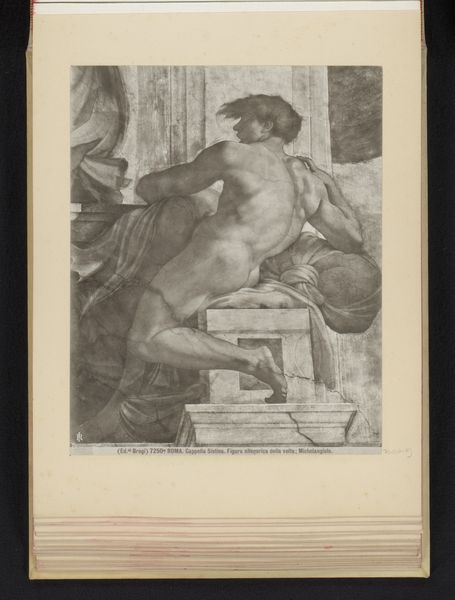

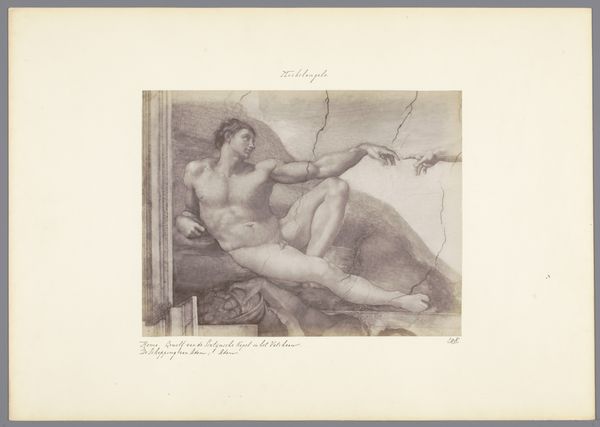

Fotoreproductie van een detail van het fresco door Michelangelo in de Sixtijnse Kapel in Rome, voorstellend een man op een sokkel c. 1875 - 1900

0:00

0:00

anonymous

Rijksmuseum

fresco, photography, gelatin-silver-print

#

fresco

#

11_renaissance

#

photography

#

gelatin-silver-print

#

history-painting

#

academic-art

#

italian-renaissance

#

nude

Dimensions: height 244 mm, width 185 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

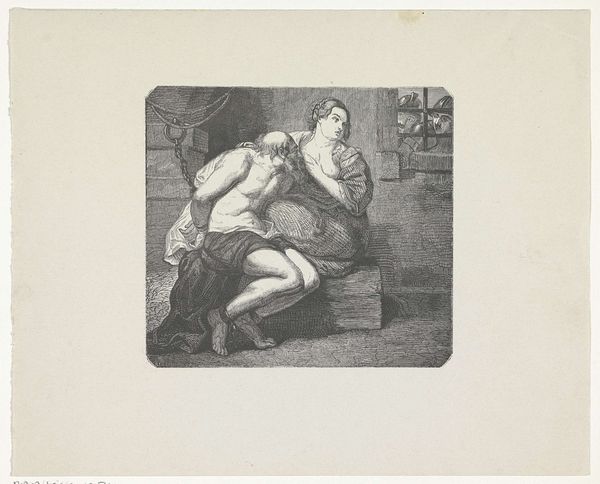

Curator: Let's discuss this striking gelatin-silver print, a photographic reproduction of a detail from Michelangelo's fresco in the Sistine Chapel, made around 1875-1900. Editor: It has such a pensive, almost burdened mood. The figure seems trapped, perhaps even reflecting on the weight of history bearing down on him. Curator: Indeed. This academic artwork really allows us to delve into the methods used to popularize high Renaissance art. Reproductions like this spread the fame and influence of Michelangelo’s frescoes far beyond the Vatican. They transformed it into an industry. Think of the resources: the labor of photography and printing processes dedicated to propagating a visual ideal. Editor: Absolutely. And looking at the subject matter, we cannot ignore the power dynamics inherent in this representation of the male nude. Michelangelo certainly situated the male body as a pinnacle of artistic expression, establishing paradigms around masculinity that artists have explored and subverted for centuries. His nude is about more than an image; it is an aesthetic value imposed on gender, labor, power. Curator: The fresco medium is also worth noting. Fresco painting demanded speed and skill, with the pigment binding to the wet plaster. Each day the artist prepared only enough plaster that they could paint within a set amount of time, known as a "giornata." The whole Sistine Chapel project would require a substantial investment, time, and the organization of labor. Reproductions offer insight into what could and could not be afforded during the Renaissance. Editor: It's impossible to forget that the chapel served as a papal chapel – a site of immense religious and political power. The body rendered here, regardless of how idealized, became a potent tool of ideological articulation, helping define standards and cultural meanings for the modern era. We can also consider questions of viewership. Who consumes this image? Curator: Exactly. The proliferation of reproductions shifted this consumption from primarily elite religious circles to a broader audience via a marketplace driven by visual technologies. Editor: Looking at it now, the crack running along the image gives us additional insight into aging and historical contingency. It brings our present into contact with the past in really poignant ways. Curator: It also offers us new material evidence for its analysis: the specific type of paper and developing processes employed at the time it was created. Editor: A collision of histories made present, then! It urges us to see more clearly, I think. Curator: I couldn’t agree more; it’s where technique and societal context so compellingly intersect.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.