drawing, print, paper, pencil, chalk, black-chalk

#

portrait

#

pencil drawn

#

drawing

#

neoclassicism

# print

#

pencil sketch

#

charcoal drawing

#

paper

#

pencil drawing

#

pencil

#

chalk

#

academic-art

#

black-chalk

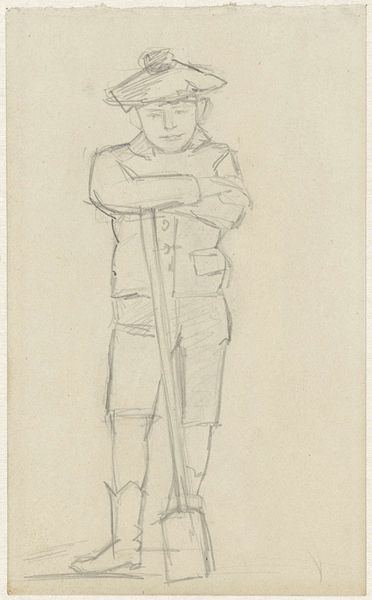

Dimensions: 351 × 226 mm

Copyright: Public Domain

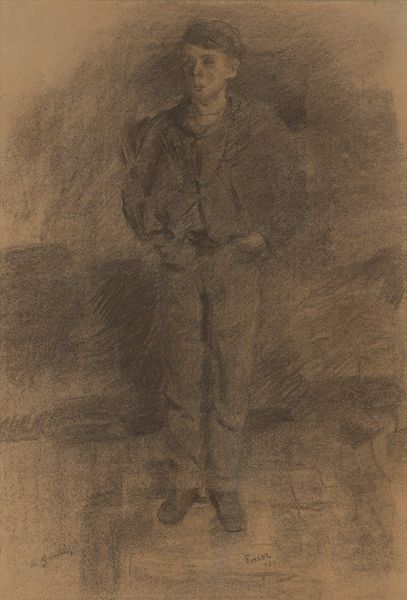

Curator: John Downman's "Standing Boy," created around 1794, greets us today. It's rendered in black chalk, pencil, and touches of white chalk on paper, now residing here at the Art Institute of Chicago. What strikes you first about this drawing? Editor: The texture, definitely. The visible strokes of the chalk and pencil give it an immediacy. He seems to be captured mid-thought, almost distracted. Is that typical for portraiture of the time? Curator: The neoclassical portraiture favored idealization, often presenting subjects in very formal poses. Downman, while working within that framework, infused a sense of naturalism, portraying the boy with a certain relaxed attitude. His hand is almost carelessly thrown behind his head, and he looks thoughtful. Editor: There's a vulnerability in that. It challenges the rigid class structures of the time by acknowledging this boy's interiority. His dress, though simple, speaks to a certain social standing, but his posture is less performative, more genuinely human. It hints at social tensions beneath the surface of apparently conventional society. Curator: Indeed. Downman was known for his ability to capture a certain elegance even in informal settings. Look at the subtle shading around the eyes, the delicate treatment of his coat. He imbues the everyday with a quiet grace that was characteristic of the time’s ideals for art’s role in public life. Editor: But who was this boy? Was he a son of privilege, merely sketched for posterity? Or did Downman see something else, perhaps a silent rebellion against expectations, a youthful challenge to the status quo within the context of late 18th-century power structures? Curator: Regrettably, we lack precise biographical details about him. Yet the artwork, particularly given its method of display, can be seen as reflecting art’s increased accessibility at this period. Museums began prioritizing broad public engagement as fundamental to civic enlightenment. Editor: It's fascinating how this seemingly simple portrait raises questions about social mobility, access, and representation. I wonder what stories this boy could tell about his place and time. Curator: I find it powerful that a simple sketch continues to spur such critical conversation centuries after its making. Editor: Exactly—art's capacity to invite dialogue across temporal and cultural contexts is one of the aspects I find most valuable.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.