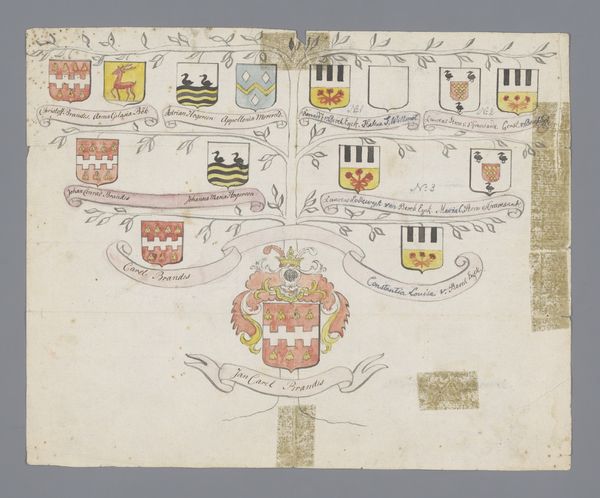

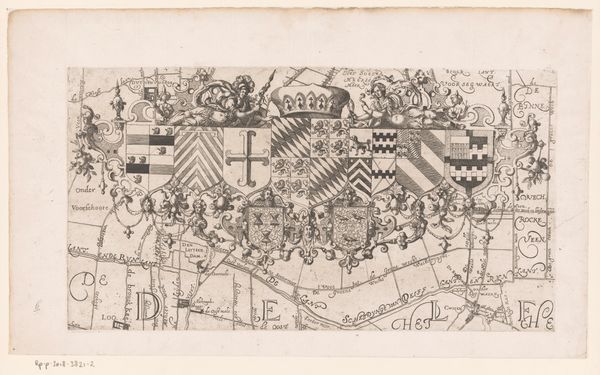

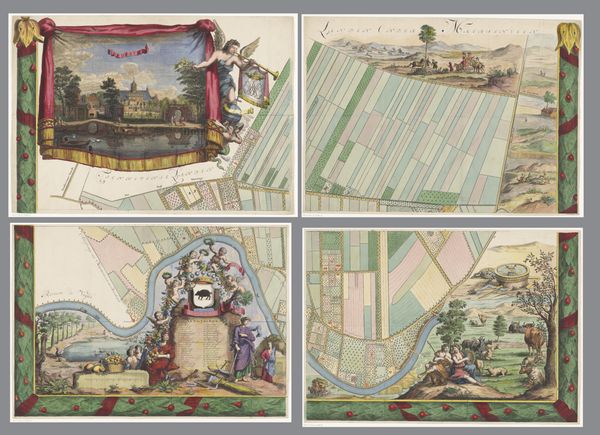

painting, print, watercolor, engraving

#

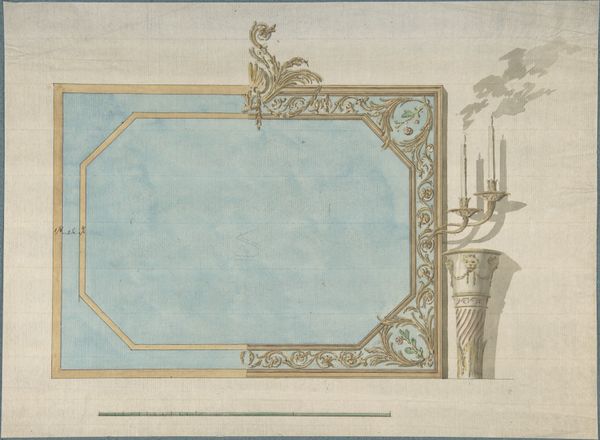

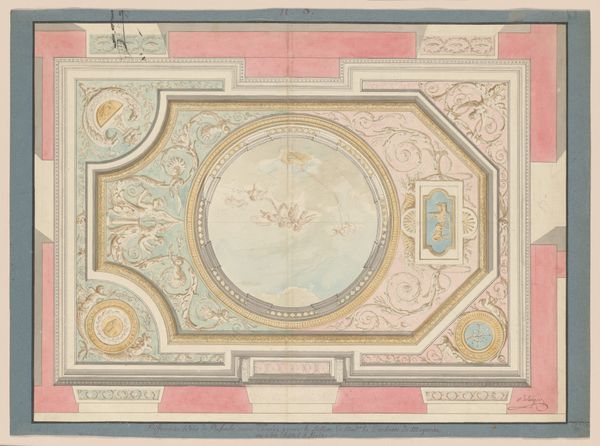

water colours

#

baroque

#

painting

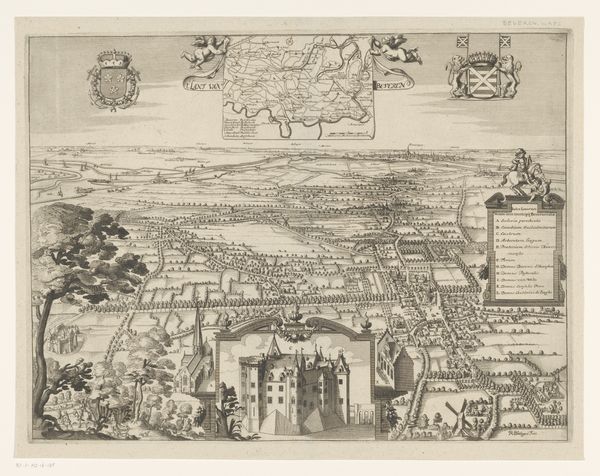

# print

#

landscape

#

watercolor

#

engraving

#

watercolor

Dimensions: height 507 mm, width 606 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: At first glance, it appears as an oddly calming pink landscape viewed through the finest screen. Like a heat map, only much, much older. Editor: Well, put your glasses on, because this isn't some hazy dreamscape. This engraving with watercolor, created sometime between 1689 and 1694, presents nothing less than "A Table of the Distances Between the Cities of Great Britain." Curator: Distances. Yes, a quite Baroque form of navigation—to render an otherwise straightforward chart so dense! It gives me a headache just looking at it, thinking about the poor traveler consulting this thing on horseback. Did they just get hopelessly lost from sheer information overload? Editor: It's all about materiality and production. Engraving allowed for the precise reproduction of this information, disseminated on paper, reaching merchants and administrators managing burgeoning trade networks. Think about the labor involved. Each mark meticulously etched, each wash of color painstakingly applied. Curator: Yet it feels as though there is some kind of tension present. All this obsessive order, a vain attempt to categorize an uncontainable world, so wonderfully absurd. Don't those floating hands with the golden squares suggest a sort of divine cartography? Editor: I think you’re onto something: standardization, accuracy – cornerstones of emerging capitalism. The symbolic significance is clear—to measure is to know and, perhaps, to control. This wasn't art for art's sake. It served a very practical purpose. Curator: Perhaps the beauty lies in its unintended poetics. Consider the act of traveling itself—a journey is less about the calculated distance and more about transformation, about becoming unmoored. That rosy haze of distance makes it more lovely than clinical. Editor: And yet we come back to the grid, that strict structure on which these early capitalist longings for both certainty and mastery are laid out. Seeing it laid bare like this offers more, and I am going to say it, "real" beauty than its flourishes of cherubs ever could. Curator: In a world increasingly obsessed with mapping and quantifying, maybe there's solace to be found in the lovely blur, in accepting the beautifully imprecise, shall we say? Editor: I concede the strange beauty of that old fashioned longing, but not the blur—but its clarity and ambition of measurement within its historical moment is most striking, at least to me.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.