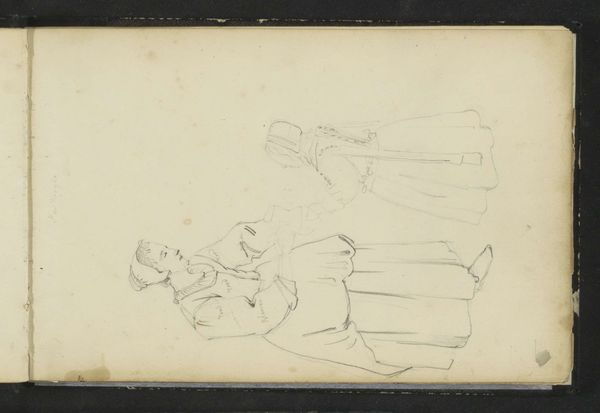

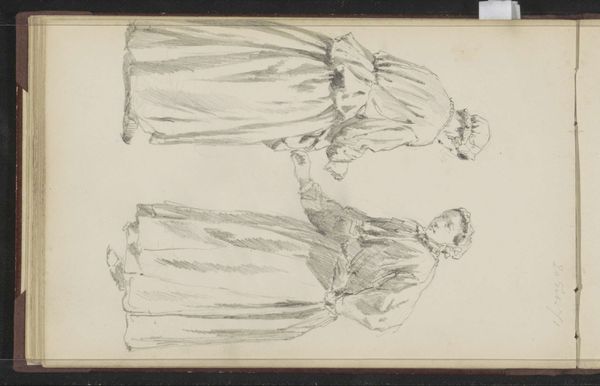

drawing, pencil

#

portrait

#

drawing

#

imaginative character sketch

#

light pencil work

#

sketch book

#

figuration

#

personal sketchbook

#

child

#

character sketch

#

ink drawing experimentation

#

pen-ink sketch

#

pencil

#

sketchbook drawing

#

genre-painting

#

storyboard and sketchbook work

#

sketchbook art

#

realism

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

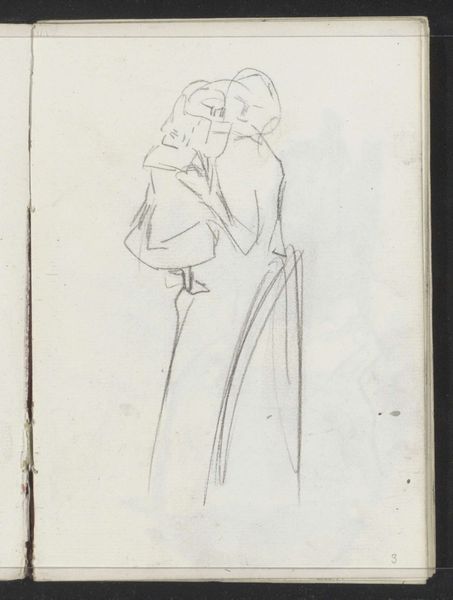

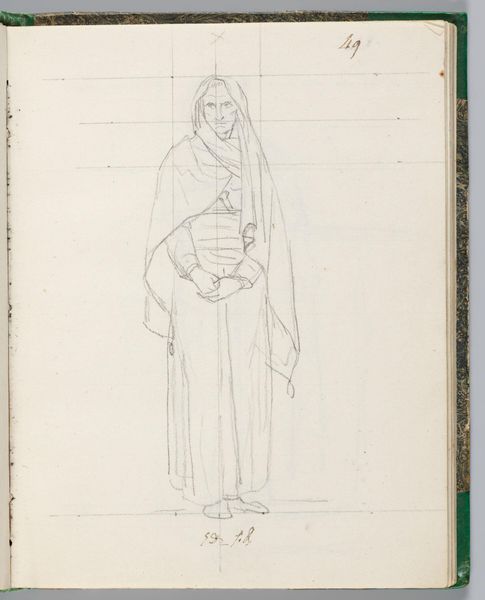

Editor: This pencil drawing, "Young Woman with a Child on Her Back" by Jozef Israëls, feels both intimate and a bit melancholic. The light pencil work makes it look delicate, but the subject—a woman carrying a child—hints at a bigger story. What do you see in this piece beyond the surface? Curator: It’s precisely that suggested story which draws me in. Israëls, a key figure in the Hague School, often depicted scenes of working-class life, focusing on the hardships faced by ordinary people. Consider the time period: 1834-1911. This drawing isn’t just about a mother and child; it speaks to the realities of labor, gender roles, and societal expectations. Think about what it meant to be a woman, particularly a working-class woman, during that era. Editor: So, it’s a commentary on the burdens women carried, quite literally in this case? Curator: Exactly. The drawing style itself is crucial here. It’s not a grand, idealized portrait. It's a sketch, almost a fleeting moment captured. It feels raw and honest. We can draw parallels with feminist discourse that challenges the romanticisation of motherhood. It acknowledges the physical and emotional labor often invisibilized. Does the child appear joyful? Consider what implications such depictions of working class family units might expose? Editor: I didn’t think about it that way, about motherhood being romanticized and this image presenting a counter-narrative. Curator: Furthermore, consider the socio-economic context of the Hague School, which championed Realism, contrasting with earlier art movements of Classicism and Romanticism, known for its idealized or heroic subject matter, which seldom captured working-class people and themes, reflecting a shift in art. How does that challenge or subvert prevailing narratives about gender, class, and identity? Editor: I see. Looking at it now, the drawing isn’t just a tender moment, but a poignant reflection on the social and economic pressures faced by women and families in that period. Curator: Indeed. Art allows us to re-examine historical narratives. We can reflect critically on representation, power dynamics, and the untold stories embedded within seemingly simple images. I leave thinking how we may continue such narratives.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.