drawing, pencil

#

drawing

#

animal

#

pencil sketch

#

landscape

#

charcoal drawing

#

figuration

#

pencil drawing

#

romanticism

#

pencil

#

watercolor

#

realism

Copyright: Public Domain: Artvee

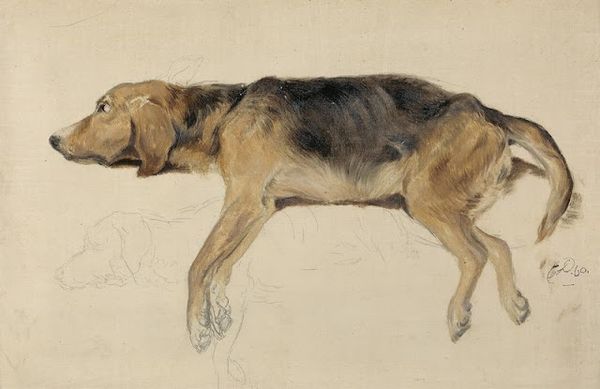

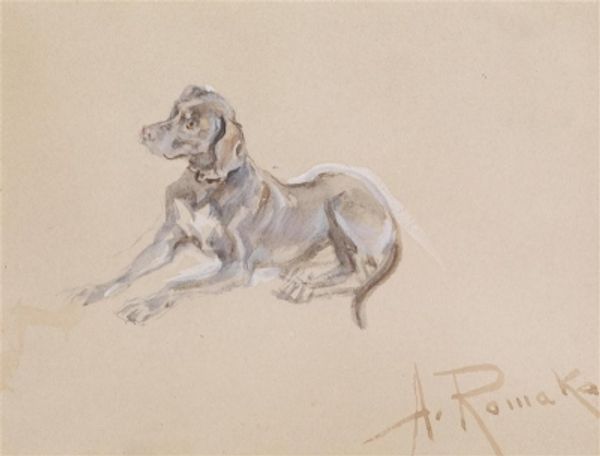

Curator: Here we have John Linnell's 1839 drawing, "Earl Talbot's Hound, Thomasine." It's rendered in pencil and watercolor. The composition features a rather noble-looking dog, presented in profile. Editor: It strikes me as a melancholy piece, almost austere in its simplicity. The limited palette emphasizes the stark beauty of the animal's form, but also a certain vulnerability, a fragility perhaps? Curator: Linnell, particularly during this period, was deeply interested in representing class and identity through his work. This dog, clearly belonging to the Earl, speaks volumes about status and ownership within the British landed gentry. Consider the meticulous detail in capturing Thomasine's lean musculature and the slightly idealized features. Editor: Absolutely. I am looking at how Linnell translated the tangible quality of fur into a tactile drawing through those varying pencil pressures and the restrained wash. You feel he worked carefully to delineate not only musculature, as you say, but bone structure too. I mean, what kind of life does a creature like that lead? Does he use certain papers? Was this hound fed properly or trained effectively? I'm thinking a lot about labor here; the dog's, the artist's, and those connected to his patron. Curator: That's fascinating, considering the prevailing social discourse regarding animal welfare during the Victorian era. Here we have an intriguing interplay between artistic expression, labor, and social commentary, which mirrors the complicated relationships that underpinned Victorian society itself. Also the question of how ownership shapes living bodies and perhaps the artistic gaze too. Editor: And let's not forget, even pencil production involved complex mining and manufacturing processes with a legacy rooted in industrial labor. All materials carry an embedded story. How different would this study feel rendered in oil paint, for instance? The accessibility afforded by watercolor opens important angles on who creates, as well as who consumes, visual arts in nineteenth-century Britain. Curator: A really crucial observation that adds an extra layer to our interpretation, especially if we consider Linnell’s own background and ambitions as an artist navigating social hierarchies. Editor: It's certainly provided a thought-provoking glimpse into nineteenth-century society through the simple medium of pencil and paper. Curator: Indeed. A single drawing has revealed intersections of class, labor, and representation—so typical of his period and hopefully giving pause for some contemporary parallels.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.