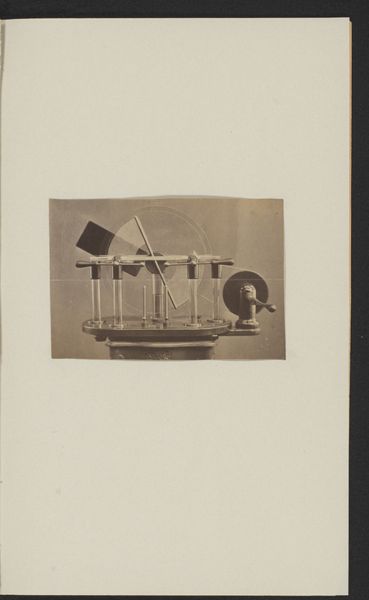

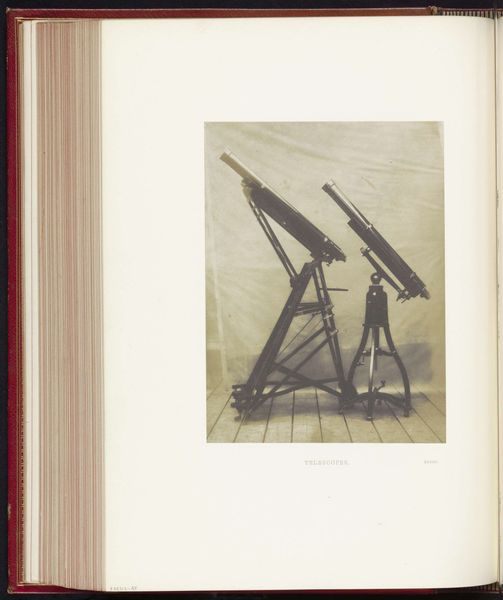

Vijf optische instrumenten, waaronder een heliostaat, van Dubosq-Soleil op de Great Exhibition van 1851 in Londen 1851

0:00

0:00

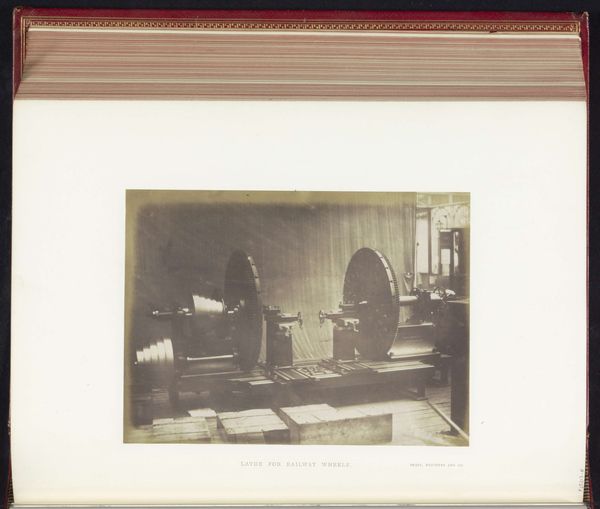

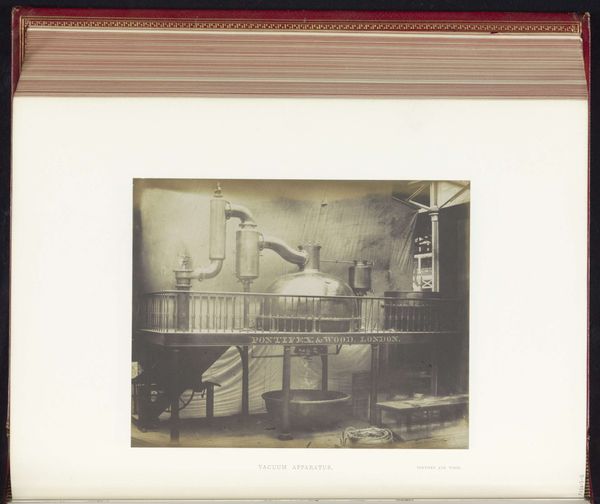

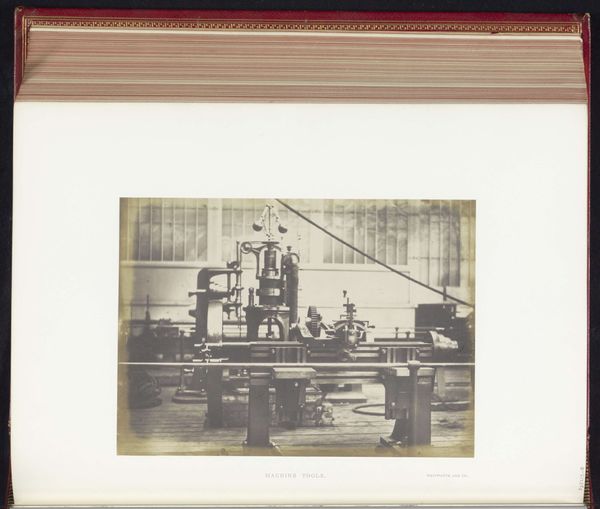

Dimensions: height 151 mm, width 198 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: This is a gelatin-silver print dating from 1851, credited to C.M. Ferrier and F. von Martens, showcasing optical instruments by Dubosq-Soleil at the Great Exhibition in London. Editor: Striking. There’s an immediate impression of austere precision. These are instruments of scientific exploration and demonstration, rendered with careful tonal detail, all presented against a fairly neutral ground. The meticulous photographic process really highlights the physical forms, right? Curator: Absolutely. These aren't merely objects, but artifacts reflecting Victorian ideals of progress. Think of the Great Exhibition itself – a massive stage for industrial and technological displays, nationalism, and the emerging culture of global trade. This image functions almost as a promotional catalogue, mediating how the company presented its innovations to potential clients. The materiality of photography itself was, of course, an object of novelty during the era. Editor: Yes, but there's a visual tension. We see the instruments themselves – crafted, tactile, weighty things made of specific materials – juxtaposed with their representation through the relatively new and immaterial technology of photography. The image is less a mere reflection, and more of a record of the labor, precision, and investment of an age in pursuing technical perfection. Look closely at the surfaces of the instruments themselves, from the gleaming brass to the polished lenses; then contrast them with the subdued tones in the silver print. The gelatin printing creates texture. Curator: And this picture circulated in its own market! We should also think about this image existing, for example, as part of a bound volume sold at a price – becoming a collectible item documenting a moment in time. It solidifies not only the industrial advancement that the objects exemplify, but it simultaneously solidifies an industrial, national pride surrounding this material, this company, and these processes. Photography here begins a circuit in consumer culture. Editor: Indeed. So this work speaks to more than mere scientific endeavor. It’s an intersection of Victorian-era commercialism, scientific optimism, and the burgeoning world of visual documentation. This still-life encapsulates not only a specific exhibit from 1851, but an idea that technological advancement can—and should—be translated into material forms and consumable goods. Curator: And that these objects and images would eventually be transformed and transformed again by the forces of their markets and contexts over time. Editor: It allows for such layered considerations when material production, photography and the archive come together.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.