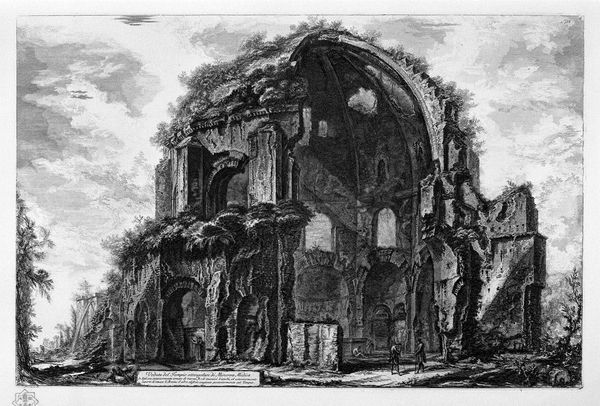

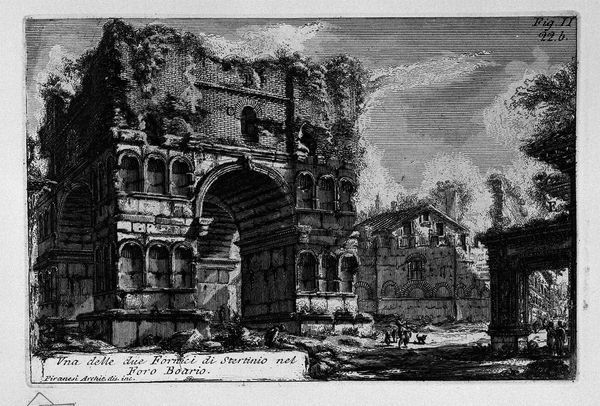

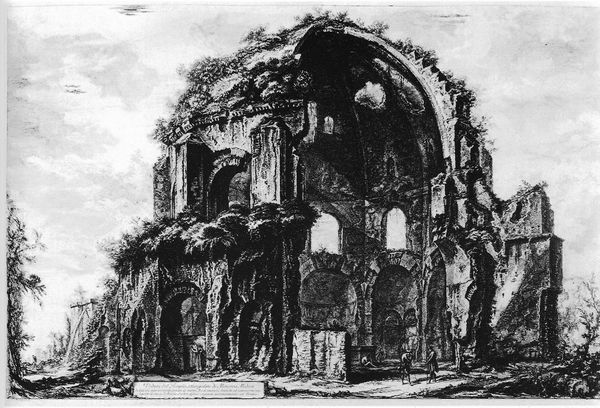

The Roman antiquities, t. 1, Plate XVI. Temple of Minerva Medica. 1756

0:00

0:00

print, engraving, architecture

#

neoclacissism

# print

#

pen sketch

#

pencil sketch

#

old engraving style

#

arch

#

engraving

#

architecture

Copyright: Public domain

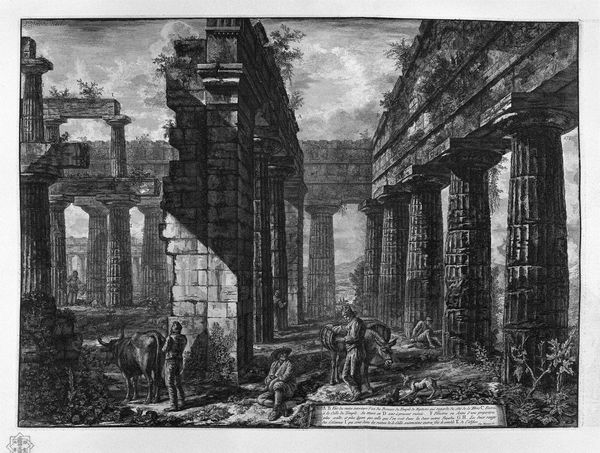

Curator: This engraving, "The Roman Antiquities, t. 1, Plate XVI. Temple of Minerva Medica," created in 1756 by Giovanni Battista Piranesi, offers a glimpse into the architecture of the past, specifically focusing on the ruins of what was once believed to be the Temple of Minerva Medica. Editor: There’s a palpable sense of melancholic grandeur here. The ruin seems to breathe, to surrender to time while still asserting its former importance. The intense contrast in shading evokes deep introspection. Curator: Piranesi was very interested in communicating the awe he experienced in Rome's remaining monuments and artifacts. We must remember, though, that what he is depicting may be incorrect. It is very difficult for archeologists, historians, and others to agree on what the so-called Tempio di Minerva Medica actually was and what its significance might have been. It now seems more likely it was an imperial nymphaeum in the Horti Liciniani, but by then, it was too late; the image had lodged itself into the popular consciousness. Editor: That image certainly reflects Neoclassical interests. One sees the careful detailing of classical forms juxtaposed with a palpable sense of decay, the kind that fuels Romantic contemplation of loss and change. This image serves as an icon of remembrance and mortality, carrying cultural memory beyond mere architectural representation. It becomes about what we feel about the ruin more than what the ruin actually *is.* Curator: I agree; its cultural impact exceeds mere historical accuracy. Prints like this one by Piranesi were central to circulating ideas about Roman architecture to a broader audience, particularly among wealthy Europeans undertaking the Grand Tour. In a way, the politics of image-making here constructs an idea of Rome, shaping historical consciousness across Europe through the visual consumption of its past. Editor: Ultimately, what captures me is how the very decay of the monument amplifies its power. It stands not as a pristine symbol of the past, but as a witness, burdened yet resolute. That visual tension resonates across centuries, informing how we perceive cultural heritage today. Curator: Indeed, and this enduring quality invites us to reconsider the ever-evolving dialogue between past and present and to accept that history is always in transition.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.