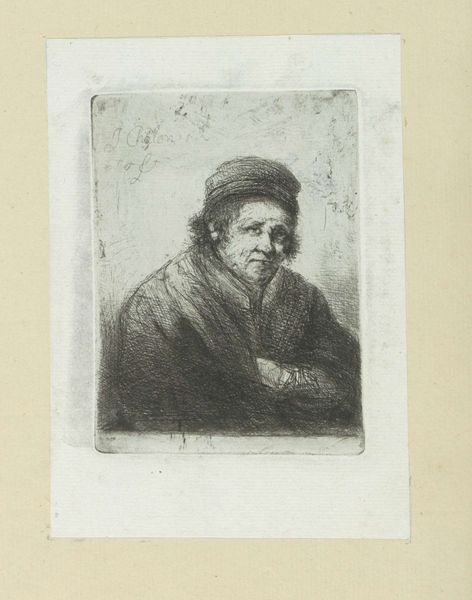

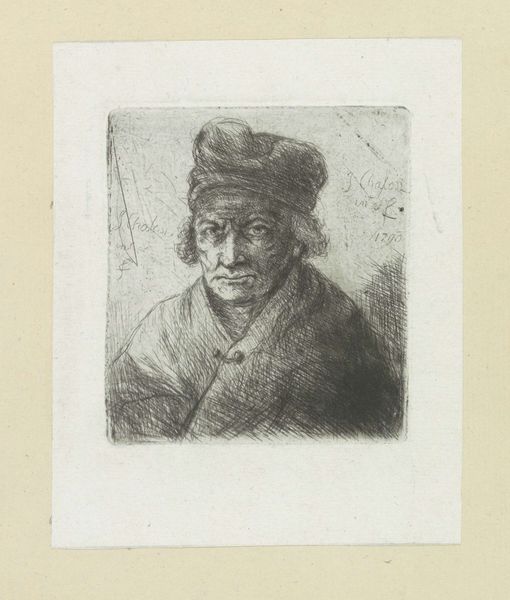

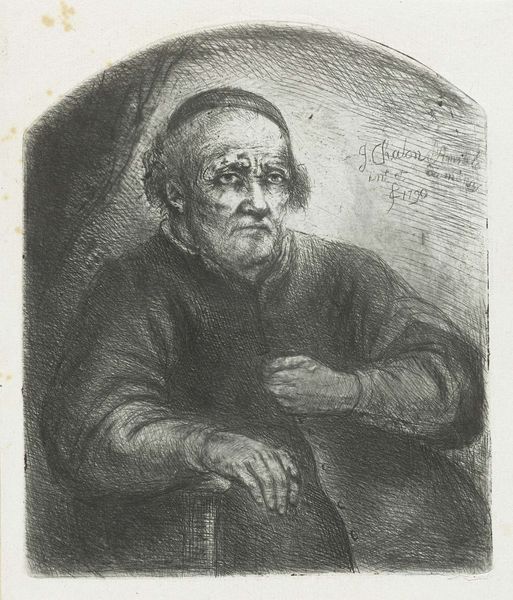

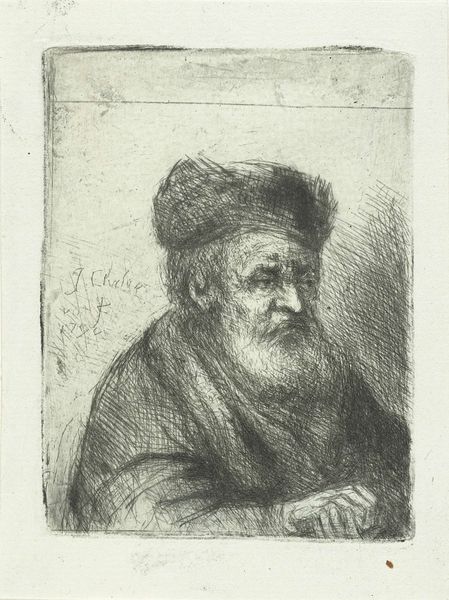

Dimensions: height 111 mm, width 83 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Here we have Jan Chalon's etching, “Volwassen man," made sometime between 1748 and 1795. Editor: My first thought? The texture. The way those etching lines give him so much weight, almost sculpting the light right off his skin. He feels substantial, doesn't he? Not fleeting at all. Curator: Definitely. And thinking about Chalon’s broader body of work, known for its social commentary and almost journalistic capturing of everyday life, it's compelling how he directs the same incisive gaze here. No grand narrative, just this very grounded portrayal of an adult male. Editor: Grounded indeed. There's a stoicism to him, a lived-in quality around the eyes. I wonder about the context of this print—who was he portraying? What statement, if any, was being made about masculinity and class? Was it subversive to depict someone ordinary with this kind of focused intensity, pushing back against depictions of the idealized nobility that filled art history? Curator: It's easy to assume a class dimension, isn't it? Though maybe it’s more about aging, just observing someone in that time in their life. Those eyes, like an ancient sea. Is this baroque naturalism offering us new lenses for seeing individual stories and struggles—ones left out by others? The very deliberate graphite sketching to the print’s medium suggests a careful labor, one of respect. Editor: Respect, yes, but I’m still struck by the sitter's presentation—his simple cap, heavy robe—versus that almost painful realism in the rendering of his features. It begs the question, "Who got to be 'immortalized,' and on whose terms?" Even his expression seems to question being memorialized. How do we decolonize historical portraiture like this, reclaim those stories, give voice to those unheard narratives etched within these very lines? Curator: That's beautifully said, really, it reframes the intent, or what we impose upon the intent now looking at art like this. Sometimes, I think portraits reach into the timeless space, to something universal. The truth of aging. Of knowing yourself, being present. Editor: Exactly. "Knowing" in that sense makes all the difference—it acknowledges not just their existence, but their subjective experience as central, which often gets erased. I suppose for me it shows, among other things, what questions can the arts open and facilitate. Curator: And from a few sketched graphite marks, the conversation flows! I'll ponder this old man, then, as an icon of enduring experience and of silent questions to art audiences now. Editor: Indeed. I am moved thinking about the man Chalon was depicting; he exists and challenges us today.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.