Copyright: Public domain

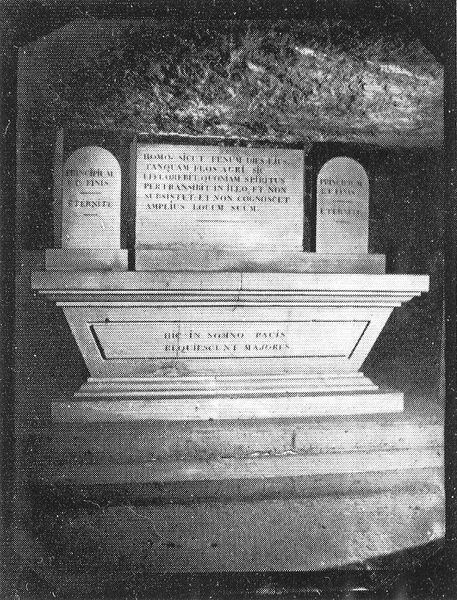

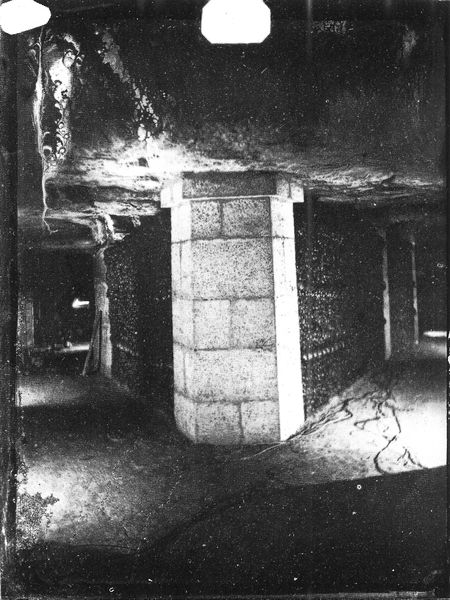

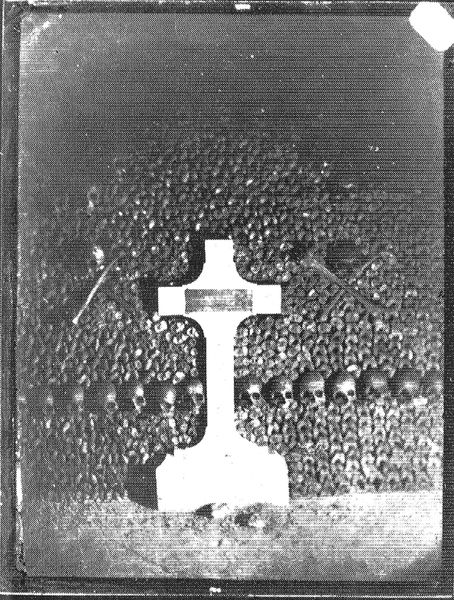

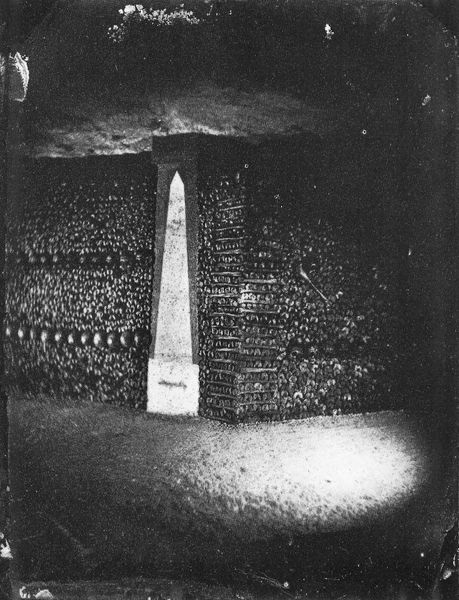

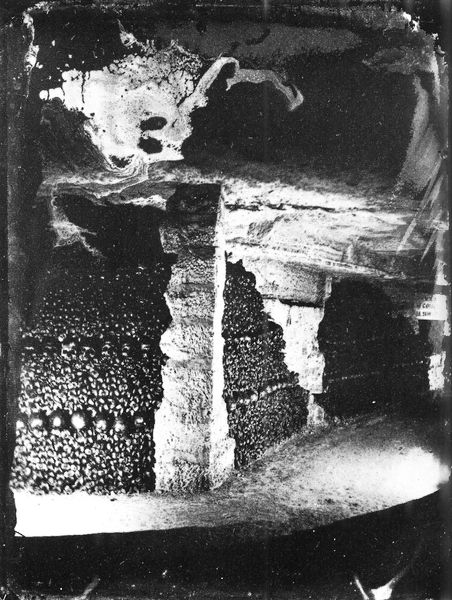

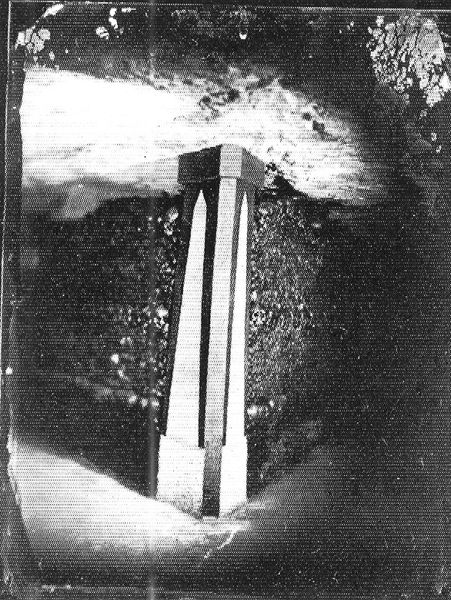

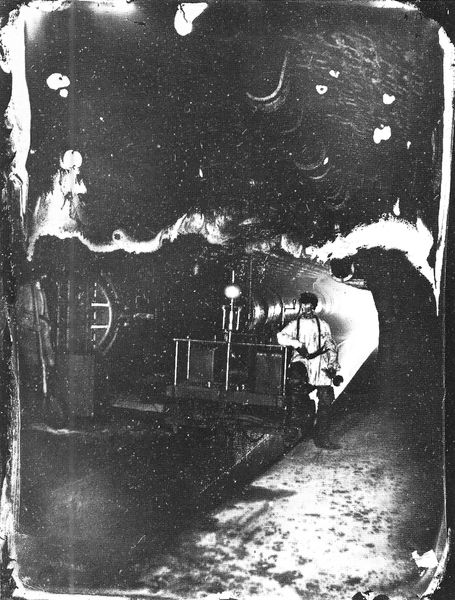

Curator: This gelatin-silver print, titled “Catacombes De Paris,” was captured by Felix Nadar around 1861. It plunges us into a shadowy space. Editor: My first impression? Eerie elegance. The monochrome palette casts a haunting aura, with what appears to be a plaque fighting against the encroaching darkness. It is an unsettling invitation, isn't it? Curator: Indeed. Nadar was a pioneer in the then-nascent field of photography, particularly his use of artificial light in these underground spaces. This image becomes more than just documentation; it's about how technology unveils the hidden. We should recall Paris’ history here too—replete with revolutions, imperial ambition, stark class divides. Do you see a connection here to urban underbellies and marginalised groups of people? Editor: Absolutely, because Paris’ underbelly also speaks of the precarious lives that are systematically buried under its structures of power. Nadar's use of light almost feels like a reclaiming or rescuing from the shadows, as the print invites us to meditate on the ethics of our vision: What do we choose to illuminate, and what do we leave in the dark? Curator: The romanticism style underscores that point, really playing up the sublime and emotional encounter, making the image a personal and, dare I say, aesthetic experience. I love the slight blur of the background that contrasts against the hyperreal textures on that slab. How does Nadar’s photograph move our understanding of landscape? Editor: It really inverts it! Landscape traditionally denotes the outside world and the beauty of nature, but here we descend to an inside landscape, where the supposed natural order gives way to death, history, and collective memory. This print serves as a great reminder that every landscape is marked with hidden histories, that can in turn be illuminated to speak truth to power. Curator: So it makes you wonder, doesn’t it, if Nadar felt like he was capturing the soul of the city itself down there in those depths? Editor: Definitely! This journey isn’t just geographical; it is also a profound sociohistorical expedition, echoing feminist notions of excavation that ask us to question the very grounds on which the past is built, and unearth histories in service of forging more liberated futures.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.