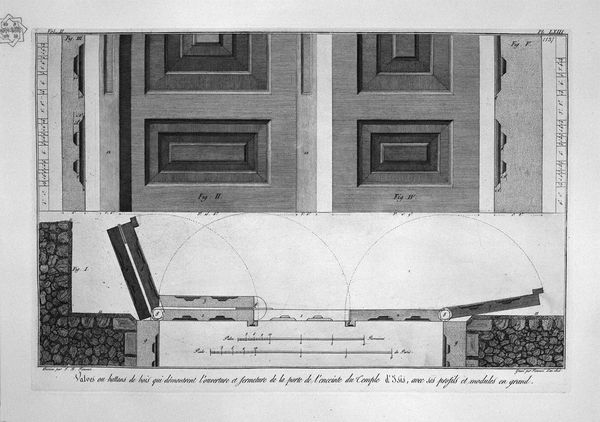

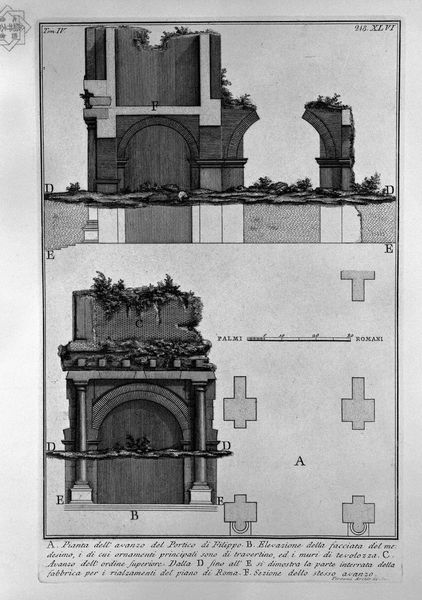

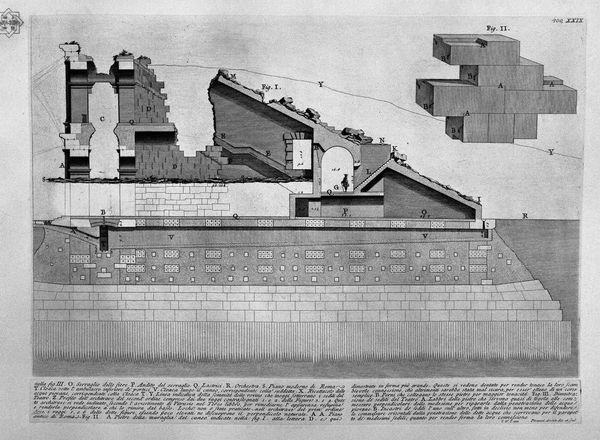

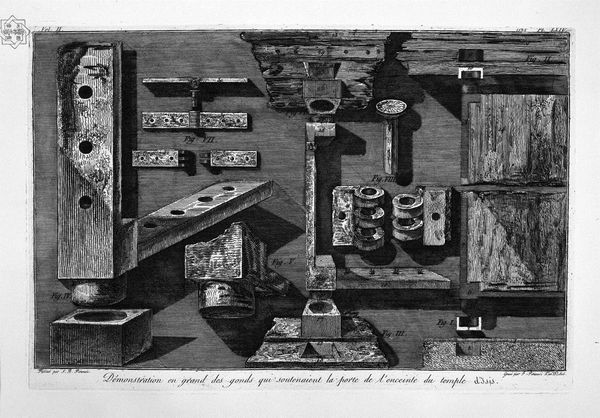

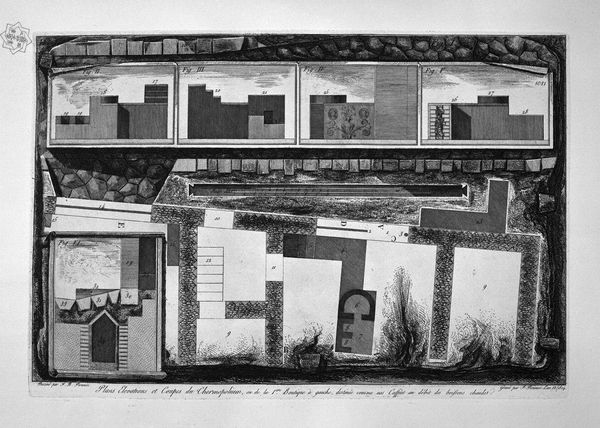

The Roman antiquities, t. 4, Plate XLI. View of one of the sides of the front of the Portico d`Ottavia, its width and construction details.

0:00

0:00

drawing, print, etching, engraving, architecture

#

drawing

# print

#

etching

#

old engraving style

#

romanesque

#

geometric

#

ancient-mediterranean

#

arch

#

line

#

history-painting

#

engraving

#

architecture

Copyright: Public domain

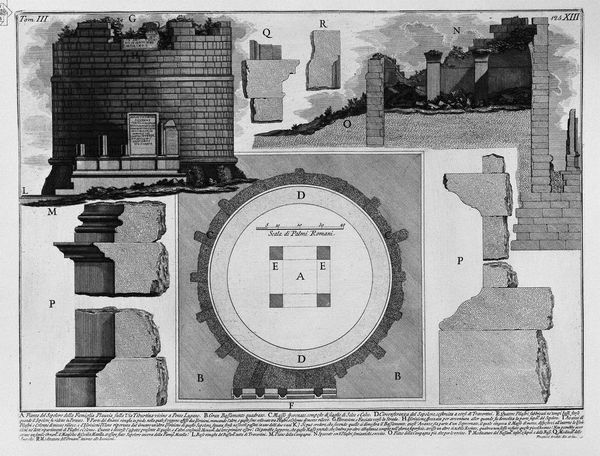

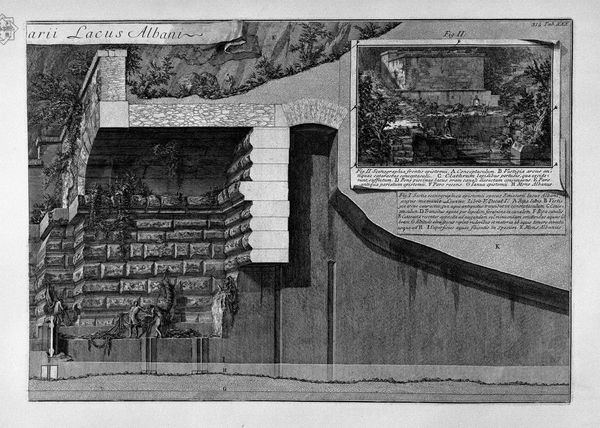

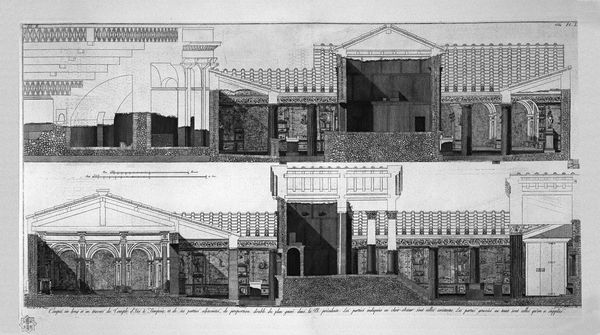

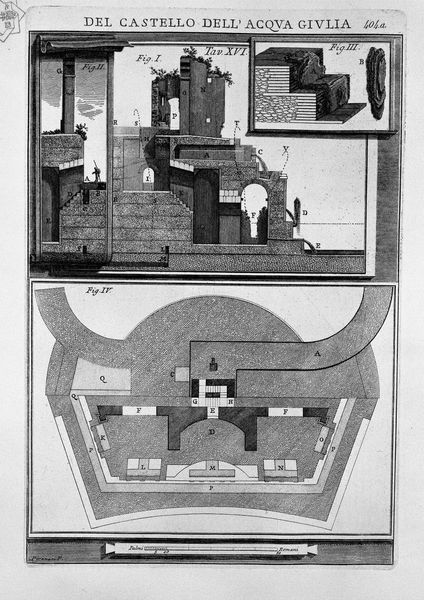

Curator: Let’s examine this engraving, “The Roman Antiquities, t. 4, Plate XLI. View of one of the sides of the front of the Portico d`Ottavia, its width and construction details” by Giovanni Battista Piranesi. Editor: It feels like an architect's fever dream – intensely detailed, yet melancholic. It captures ruins not just as objects but as powerful, if decaying, presences. I immediately key into how it’s assembled…layers of architectural drafting over seemingly raw observation. Curator: Indeed, the historical context is crucial. Piranesi created this work to engage with questions of power. Who controls the narrative and the representation of ancient Rome? How do we position Italian identity, the authority of the papacy, against the glory of the Empire? These images, so readily accessible, serve as a touchstone. Editor: Right, the material fact that this is a print means wider accessibility. This shifts conversations beyond elite architectural circles, and I'm drawn to his lines… the intense etching suggests both precision and an almost violent engagement with the copperplate. We're witnessing a physical act of interpretation here. Curator: Consider also Piranesi’s role as a Venetian working in Rome. The imagery evokes not merely architectural drafting but perhaps also stage design. He seems to choreograph an encounter between the viewer and the Roman past. The shadows accentuate not simply decay, but a kind of theatrical collapse. This engraving becomes a meditation on cultural inheritance. Editor: The visible labor becomes part of the artwork’s meaning. High art is meeting what some may categorize as “mere” documentation, as well as the industrial process of reproduction and dissemination. It all collapses binaries. He almost seems to prefigure conceptual art movements. It really encourages us to rethink the role of labour, production and access. Curator: Absolutely, in Piranesi's hands, documentation itself becomes a radical act, capable of transforming our understanding of the past. And that opens it to endless contemporary reflections and discourse about history, colonialism, power and access. Editor: It forces a kind of active witnessing, making visible not just stone, but the tools and hand that helped render the view. And maybe even inviting a whole reassessment of "grand" histories from an utterly ground-up, materialist perspective.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.