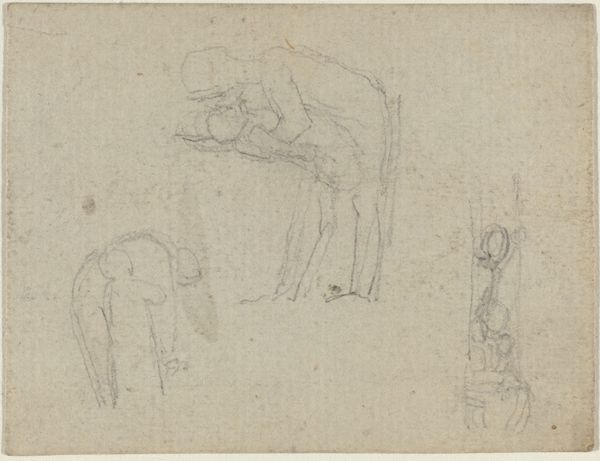

Dimensions: sheet: 8.4 × 7.8 cm (3 5/16 × 3 1/16 in.)

Copyright: National Gallery of Art: CC0 1.0

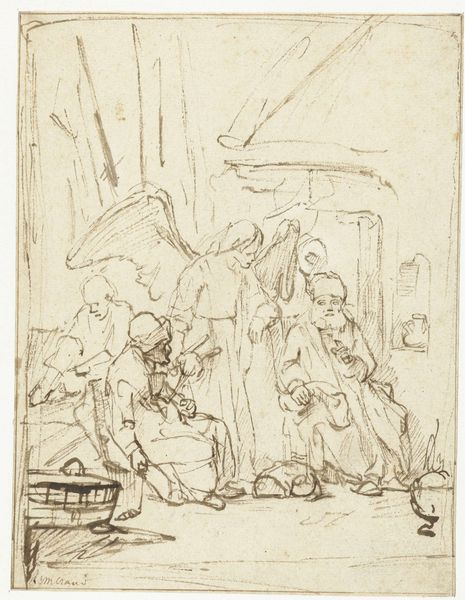

Curator: Elihu Vedder's pencil drawing, "Son and Donkey," created around 1859, immediately strikes me with its ethereal, almost dreamlike quality. It feels unfinished, pregnant with potential stories. Editor: It does have that sketch-like intimacy. For me, what stands out is the way it positions a mundane scene—a child on a donkey—alongside what appears to be some kind of ritualistic activity with veiled women and vessels. There’s a tension there, a commentary perhaps on the juxtaposition of everyday life and sacred tradition. Curator: Exactly! Vedder had such a deep interest in symbolism and allegory, stemming from his time amongst the Pre-Raphaelites in Florence. This interplay could be interpreted as a questioning of established religious narratives, maybe even the intrusion of innocence represented by the child into a realm of serious belief. I love that uncertainty. Editor: Uncertainty sells! The donkey seems quite deliberate though. The Romantic era adored pastoral life—we've got nature, peasantry. But its placement almost facing *away* from the ritual might suggest disillusionment with these idealised constructs of purity. Instead, a yearning gaze towards everyday struggles... if a donkey can yearn, of course. Curator: He probably could, given how beautifully rendered it is. But looking closer at these almost-veiled women, one lifting the water vase atop her head so confidently—their faces seem timeless. Vedder loved evoking classicism as a means to critique the politics surrounding American expansionism during that period. The vessel becomes something charged. Editor: Interesting. These women take on more than a decorative element then, especially since America often positioned itself as the natural inheritor of Europe’s and even older empire's power through similar iconography...it certainly enriches our understanding of the artwork in this context, not as an isolated pastoral drawing but an active response toward nation building agendas. Curator: Vedder had this knack of weaving personal doubt and larger societal critique with art that never shouts but rather whispers and ponders aloud; he created spaces for thoughtful reflection. Editor: And hopefully, we have achieved the same here; offering a point for visitors to connect to its beauty and cultural power long after they leave our galleries.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.