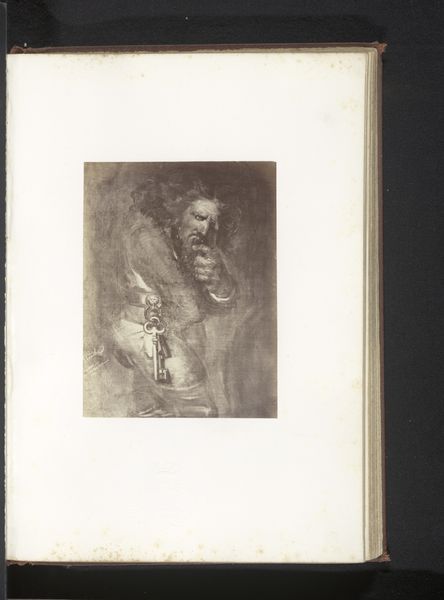

Reproductie van een gegraveerd portret van Karel I van Engeland before 1897

0:00

0:00

anonymous

Rijksmuseum

Dimensions: height 154 mm, width 113 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

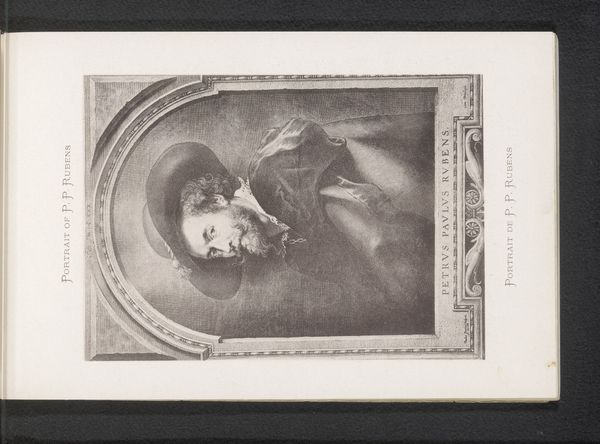

Curator: This is a reproduction of an engraved portrait of Charles I of England, after Van Dyck, dating from before 1897. It's currently held in the Rijksmuseum collection. Editor: There's an immediate gravitas here; even in reproduction, you sense the power implied. I'm struck by how the composition leads the eye, almost brutally, from the king's face down to the symbols of his reign laid aside. The almost stark use of light and shadow emphasises this melancholy. Curator: Absolutely, and knowing a bit about Charles I's reign, which culminated in his execution, that melancholic element rings true. He believed in the divine right of kings and often clashed with Parliament. Van Dyck was his court painter, effectively managing Charles's image as a symbol of authority. This print, circulating after the fact, participates in a posthumous shaping of his narrative. Editor: Precisely, the very deliberate choice to depict Charles with his hand resting near the discarded crown – a powerful visual motif – conveys loss. What I find captivating is the intricate detail achieved solely through the engraving process; look at the lines giving shape and weight to the armour, and then notice how that stark metal texture is contrasted with the softer velvet draping in the background. It plays beautifully with contrasts of fragility and resilience. Curator: You've put your finger on the Baroque elements beautifully, especially those dramatic contrasts. Furthermore, the print's existence, its republication so long after Charles’s death, illustrates how images of power continue to resonate politically. Were these disseminated for nostalgia, Royalist sympathy, as historical artifact, or simple commodity for consumption by curious audiences? Editor: All those readings, most likely! It serves as a window onto how an image transforms and circulates. Its power rests within its aesthetic design and material execution—the line, texture, form are all purposefully chosen—while its importance hinges on the subject. It gives me something to think about how a royal portrait becomes an artifact. Curator: Indeed, reflecting on it as artifact opens more and more doors into our understandings about royal display, historical sympathy, and even revolution. Editor: I'll definitely be seeing Van Dyck differently now, looking closely to grasp the complex political forces always bubbling underneath.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.